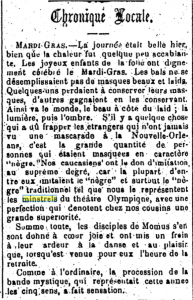

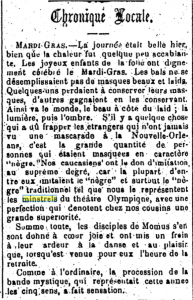

Mardi Gras – It was a beautiful day yesterday, even though the heat was somewhat oppressive. The joyful children of the chaos celebrated Mardi-Gras with dignity. The balls/dances were not empty of beautiful or ugly masks. Some people failed to keep their masks on, while others maintained them. And so went the world, beautiful alongside ugly; light, then shadow. If there was anything that would have struck strangers who had never seen a Mardi-Gras masquerade in New Orleans, it would be the large quantity of people who had masks depicting a “negro” character. Our caucasians have the gift of imitation, to a high degree/standard, because the greater part among them imitate the “negro,” and above all the traditional “negro” which is represented to us by the Olympic Theatre minstrels, with a perfection that denotes to our cousins’ home (as belonging to our cousins, either referring back to the Theatre minstrels or to caucasians) a grand superiority. (1)

Mardi Gras – It was a beautiful day yesterday, even though the heat was somewhat oppressive. The joyful children of the chaos celebrated Mardi-Gras with dignity. The balls/dances were not empty of beautiful or ugly masks. Some people failed to keep their masks on, while others maintained them. And so went the world, beautiful alongside ugly; light, then shadow. If there was anything that would have struck strangers who had never seen a Mardi-Gras masquerade in New Orleans, it would be the large quantity of people who had masks depicting a “negro” character. Our caucasians have the gift of imitation, to a high degree/standard, because the greater part among them imitate the “negro,” and above all the traditional “negro” which is represented to us by the Olympic Theatre minstrels, with a perfection that denotes to our cousins’ home (as belonging to our cousins, either referring back to the Theatre minstrels or to caucasians) a grand superiority. (1)

The last short segments of the article go on to describe one or two other events which occurred at the Mardi Gras parade, including a mysterious musical group. However, this is the most striking segment. Rarely, aside from a description of coming musical acts, is blackface or minstrelsy so directly addressed in the newspaper articles of this particular decade (at least of those I encountered). It’s an interesting peek into history to see celebrations such as Mardi Gras occurring during a time that we usually only study to discuss the violence that was committed.

This article is from 1869, only about 30 years after the first Mardi Gras parade was held in New Orleans in 1837 and 4 years after the end of the Civil War. The tradition was brought to the area by French colonisers when Louisiana and the surrounding area were still under French control. It has many ties to the Brazilian celebration of Carnival (2).

The attitudes portrayed here are unclear. The New Orleans Tribune, which published this article, was an African-American publication, and yet it seems to paint quite a complimentary picture of white folks in blackface. I believe, however, that the over-the-top, complimentary wording is likely ironic – it certainly came across that way on my first reading, although it may not be as clear in my rough translation, given above. Minstrelsy was still quite in its height in the South, where it became more popular after the Civil War by leaning into the derogatory, rather than abolitionist, ties. It may very well have been unwise for a black paper to be publicly decrying minstrelsy and white participants in Mardi-Gras, hence the use of irony.

This time is also the origin of another very complicated Mardi Gras tradition. Benevolent Aid Societies came into being after the Civil War as a form of community insurance among black members of these societies – they could provide financial and other support for those who fell ill or lost family members. From these Aid Societies eventually came a group known as the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club, which formed under that name in 1909 and still exists today (3).

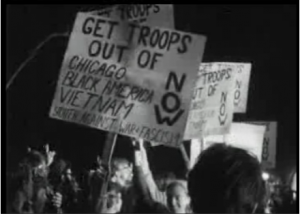

As part of the Mardi Gras parade, this social and activist club has traditionally dressed in costumes representing Zulu warrior garb, including face painting. Now a multi-racial organisation, all members of the club, regardless of race, dress this way. However, while native Zulu face painting usually involves the bright colours seen in the costumes, the Zulu club relies on black (and some white) face paint. This has caused controversy several times in the club’s history, most notably in the 1960s, when it was condemned by several members of the Civil Rights movement as promoting negative stereotypes. Membership of the club dwindled to only about a dozen members that decade, and they switched to wearing masks instead of paint (3, 4). Since then, the Zulus’ numbers have increased again and transitioned back to face paint, causing yet another controversy in 2018. Whether they are drawing on the tradition of blackface, and whether it matters, is very much up for debate. Zulus claim that they are making no effort to conceal their race or pretend to be what they are not, that they are showing a positive portrayal, that it is a long standing tradition, and that it is not based in blackface. The last claim in particular is difficult to prove, although certainly their intention is important. The controversy in ongoing, but the overall consensus seems to be that the Black leaders of the club have the right to decide whether it is appropriate for their members to dress up the way they do. As long as they are deciding that it is, many other prominent figures have refrained from condemning the practice (4).

We must consider and decide, at least for ourselves, whether it makes a difference who is portraying a negative stereotype or drawing on a painful history, as well as their intention. Can blackface, in any form, be reclaimed?

- “Chronique Locale.” New Orleans Tribune (New Orleans, Louisiana), February 10, 1869: 1. Readex: African American Newspapers.

- Wikipedia contributors, “Mardi Gras,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Mardi_Gras&oldid=916886656 (accessed October 3, 2019).

- Becknell, Clarence A, et al. “History Of the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club.” Zulu Social & Pleasure Club, www.kreweofzulu.com/history.

- Krupa, Michelle. “The Black Leaders of an Iconic Mardi Gras Parade Want You to Know Their ‘Black Makeup Is NOT Blackface’.” CNN, Cable News Network, 5 Mar. 2019, www.cnn.com/2019/02/16/us/zulu-new-orleans-blackface/index.html.

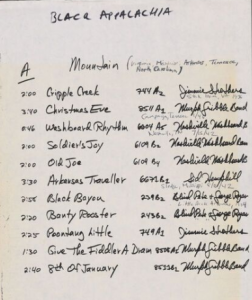

When I found a set of manuscripts collected by Alan Lomax on the playing of musicians in Black Appalachia, the last thing I expected was to end up reading about Earl Scruggs. Nevertheless, this letter from Stu Jamieson on field recordings done in 1946 of a trio of Black Appalachian musicians connected directly into our discussions of bluegrass music from Thursday’s class. The recordings this letter is referencing are of Murphy Gribble, John Lusk, and Albert York on banjo, fiddle, and guitar respectively. Apparently a banjo player himself and familiar with the rise of bluegrass by the time this letter was written in about 1978, Jamieson writes to a friend and scholar at the Library of Congress about the Gribble’s particular styles of banjo picking and fingering. As with Bill C. Malone, part of the reason his recounting is convincing because of his own study and experience with the styles he discusses.

When I found a set of manuscripts collected by Alan Lomax on the playing of musicians in Black Appalachia, the last thing I expected was to end up reading about Earl Scruggs. Nevertheless, this letter from Stu Jamieson on field recordings done in 1946 of a trio of Black Appalachian musicians connected directly into our discussions of bluegrass music from Thursday’s class. The recordings this letter is referencing are of Murphy Gribble, John Lusk, and Albert York on banjo, fiddle, and guitar respectively. Apparently a banjo player himself and familiar with the rise of bluegrass by the time this letter was written in about 1978, Jamieson writes to a friend and scholar at the Library of Congress about the Gribble’s particular styles of banjo picking and fingering. As with Bill C. Malone, part of the reason his recounting is convincing because of his own study and experience with the styles he discusses.