After reading Chapter XXII of George Pullen Jackson’s 1943 book White and Negro Spirituals, I was surprised to find just how much mental gymnastics the scholar was willing to do to support his claim that African Spirituals were primarily authored by white people.

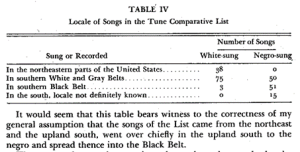

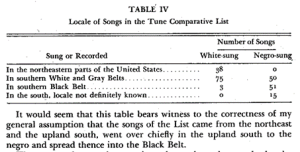

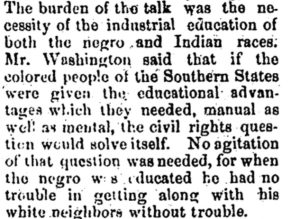

In one attempt at scholarship, Jackson uses a table he made of the number of songs sung by white and Black people regionally as “evidence” that the songs in the list traveled from North to South, from white communities to Black communities.

There are a lot of questions to be asked of Jackson, like How do you know the songs didn’t spread from South to North and How do you know this dataset is at all accurate since songs are being created all the time? However, I don’t think those questions are particularly interesting, as it is clear to me that Jackson was more interested in proving his biases than in thorough scholarship.

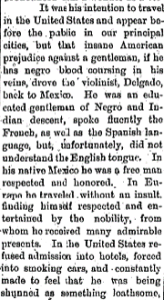

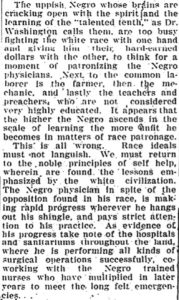

What I was interested in was the history of crediting white people for Black music, and how that legacy affects us today. What I found was an 1861 article in New York Monthly Magazine entitled “NEGRO MUSIC AND POETRY.” In it, author William H. Holcombe attempts at an ethnographic account of African American music, which is far from scientific and full of assumptions that justify the dominant worldview of white slaveholders. The part of the article that stood out most to me came after the author had spent a few lines speaking to the music’s beauty (although of course, reminding the audience that this music is not nearly as difficult or as evolved as “the grand operative style.”) After describing the beauty, the author adds “But really this negro music is none of your concert-room Ethiopian melody-operatic airs with burlesque words, extravagantly shrieked out by peripatetic white gentlemen with mammoth shirt-collars, and faces blackened with burnt cork” (Holcombe).

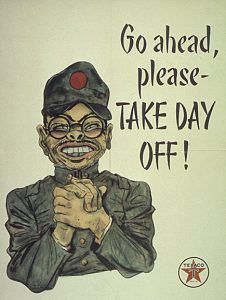

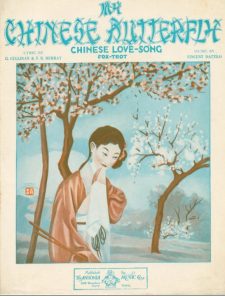

The practice that Holcombe is describing is minstrelsy, an extremely popular form of American musical entertainment developed in the 1830s where white performers would darken their faces and perform racist caricatures of enslaved Africans (National Museum of African American History & Culture). There is an irony in Holcombe’s statement that the music of real enslaved people is “none of your concert-room Ethiopian melody-operatic airs,” because he is saying that the caricaturized version of Black music that white slaveholders stole for their entertainment is somehow better or more impressive than the real thing.

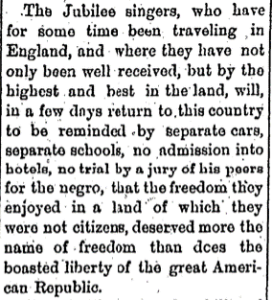

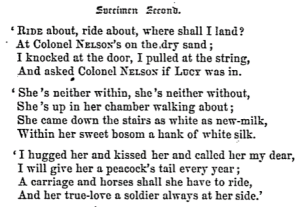

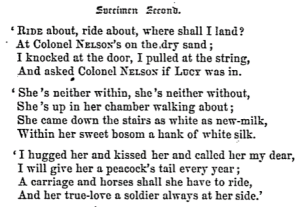

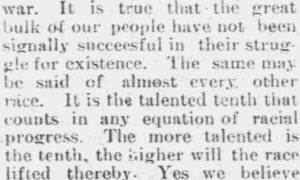

Towards the end of the section, Holcombe shows some examples of poetry written by enslaved people. Of this poem he writes, “This last I suspect to be the production of some white school-boy, or at least of some very aristocratic specimen of the negro troubadour” (Holcombe). Even in his examples of Black poetry, the author refuses to give credit to the Black artists who created this poem.  The failure to credit Black people for their art is something we discussed a lot in Intro to Musicology. For example, we discussed how Elvis Presley became popular largely by performing songs by Black singer/songwriters without giving proper credit. This may not have the same blatantly racist intention as American minstrelsy, but there is still a disturbing element of the desire to own Black art, the way the white slaveholders asserted their ownership by caricaturizing music they had stolen from Black people.

The failure to credit Black people for their art is something we discussed a lot in Intro to Musicology. For example, we discussed how Elvis Presley became popular largely by performing songs by Black singer/songwriters without giving proper credit. This may not have the same blatantly racist intention as American minstrelsy, but there is still a disturbing element of the desire to own Black art, the way the white slaveholders asserted their ownership by caricaturizing music they had stolen from Black people.

Works Cited

Holcombe, William H. “SKETCHES OF PLANTATION-LIFE: NEGRO MUSIC AND POETRY.” The Knickerbocker aka New York Monthly Magazine, vol. 56, no. 6, June 1861, ProQuest.

Jackson, George Pullen. “CHAPTER XXII: WHEN, WHERE, HOW, WHY DID THE WHITE MAN’S SONGS GO OVER TO THE NEGRO?” White and Negro Spirituals: Their Life Span and Kinship, J. J. Augustin Publisher, January 1943.

National Museum of African American History & Culture. “Blackface: The Birth of An American Stereotype.” Accessed 2nd October 2021. https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/blackface-birth-american-stereotype.

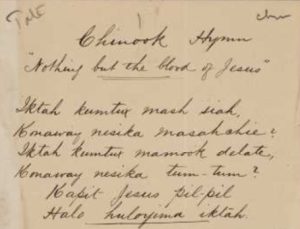

I think it is puzzling to find hymns that have been translated into the languages of indigenous peoples, because the ultimate goal of ministers like Charles Montgomery Tate was to assimilate Native Americans into white Christian culture, robbing them of their traditions and even their languages; the Chinookan languages are in danger of extinction, with all of the native speakers of the languages deceased, and very few speakers left at all (

I think it is puzzling to find hymns that have been translated into the languages of indigenous peoples, because the ultimate goal of ministers like Charles Montgomery Tate was to assimilate Native Americans into white Christian culture, robbing them of their traditions and even their languages; the Chinookan languages are in danger of extinction, with all of the native speakers of the languages deceased, and very few speakers left at all (