From spirituals sung in clandestine church settings to uplifting anthems echoing throughout Civil Rights marches, gospel music is truly a cornerstone of the African-American cultural experience. This genre, steeped in faith, resilience, and a profound sense of community, played a pivotal role in galvanizing unity throughout the turbulent era of the Civil Rights Movement. 1 As African Americans grappled with racial inequality and fought valiantly for their rights, the stirring sounds of gospel music served as a collective heartbeat – a connecting thread woven into the historical tapestry of their struggle for freedom.

Rev. Lewis Aids Rights Efforts

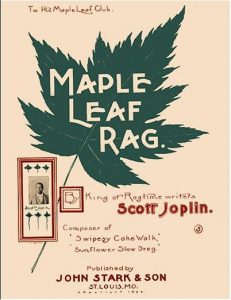

Parallel to this powerful gospel tradition, another groundbreaking genre emerged – Jazz. Like an audible mosaic of spontaneous creativity, Jazz is quintessentially American, with its deepest roots fastened in African-American expression. The playful liberties taken with melodic structures and rhythms, and the inherent emotional rawness, made Jazz the innovative art form it is today. It quickly became the voice of a generation eager to express their experiences, trials, and triumphs.

However, the path wasn’t always melodious harmony for these two genres coexisting within the African-American music scene. Gospel, with its sacred origins and divine objective, often found itself at odds with Jazz, seen by some as secular and irreverent. The Jazz influence, with its characteristic ‘swing’, trickled into gospel music which stirred controversy among traditionalists. Some pastors and churchgoers feared that the sanctity of gospel songs would be diluted, diverting from their primary purpose of worship and spiritual connection. 2 This line of thinking is similar to most religious and musicological figures of the early churches, except they took a more extreme view, sometimes banning music altogether. 3

Despite these clashes, the genres managed to maintain a symbiotic relationship. Gospel and Jazz, like two sides of the same coin, symbolize unique facets of African-American identity – faith on one side and freedom of expression on the other. Both have left an indelible mark on American music, painting a soulful picture of cultural transformation and resilience.

Footnotes

1 “Rev. Lewis Aids Rights Efforts.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Feb 29, 1964. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/rev-lewis-aids-rights-efforts/docview/493071059/se-2.

2 “Charges Singers with ‘Jazzing’ Gospel Music: Composer Issues Blast at Gospel Choir Confab.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Aug 11, 1951. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/charges-singers-with-jazzing-gospel-music/docview/492830346/se-2.

3 Weiss, Piero, and Richard Taruskin. Music in the Western World. 1984. Pages 5-11, 21-27.