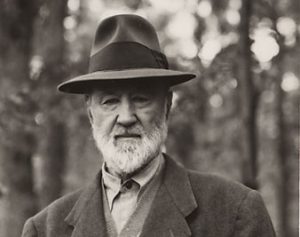

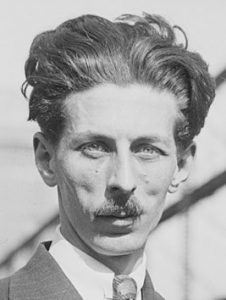

Huddie Ledbetter, or more widely known as Leadbelly, remains to this day as one of the most significant blues musicians of the 20th century, sparking inspiration in countless musicians throughout the past century like Bob Dylan, Little Richard, and Brain Wilson. His iconic singing voice and guitar playing have also been key in defining for many people a truly American “folk” music. This association as a significant music for American identity, however, did not happen by chance or solely due to Leadbelly’s virtuosity and musicianship. John Lomax, the American folk music collector, is responsible for the first recordings of Leadbelly, which happened when Lomax was visiting American prisons in search of “unadulterated” American folk music. The story of Leadbelly and Lomax’s intermingled careers is told in the March of Time episode titled “Leadbelly,” showing their first meeting and recordings at the Louisiana State Penitentiary where Leadbelly was serving time, as well as further into Leadbelly’s career and how Lomax was largely responsible for Leadbelly’s success, taking him around the country to colleges, concert halls, and to Lomax’s own home in the North. While the short film’s focus seems to be a celebration of the musicianship and career of Leadbelly, John Lomax’s immense influence on the narrative of Leadbelly seems to overshadow the musician himself.

The film’s awkwardness seems to come not only from the fact that Lomax and Leadbelly both seemed to be following a script to reenact their meeting and interactions together, but also from the relationship between the two that the film depicts. Specifically, it is hard to ignore the issue of race here, as the film seems to depict a sort of idealized version of a master/slave relationship. The way Leadbelly is shown to have begged to be Lomax’s “man” and his referring to Lomax as “boss” and “sir,” as well as Lomax presenting himself in a way that makes him to be the hero of the story for taking in the underprivileged minority, all give the film a tone that feels problematic, though this may be a product of viewing such a film in the 21st century.

The importance the film places on Lomax is, however, appropriate in a way that was perhaps not intended. The creation of a national identity through the folk music of particular black musicians uninfluenced by commercial music of the time was a deliberate act by John Lomax, scholar Benjamin Filene claiming that the Lomax brothers were “creators as much as caretakers of a tradition” (Filene 604). Essentially, what became known as true American folk music was shaped by people like the Lomaxes’ own visions of what that means. Viewing this film under such a lens perhaps makes John Lomax’s significance within the film make a tremendous amount of sense, even though it may take away from the incredible musician that is Leadbelly himself.

Works Cited:

Filene, Benjamin. “‘Our Singing Country’: John and Alan Lomax, Leadbelly, and the Construction of an American Past.” American Quarterly, Vol. 43, No. 4, pp. 602-624.

N.A. “Leadbelly.” March of Time, Vol. 1, Ep. 2, Home Box Office, 1935.