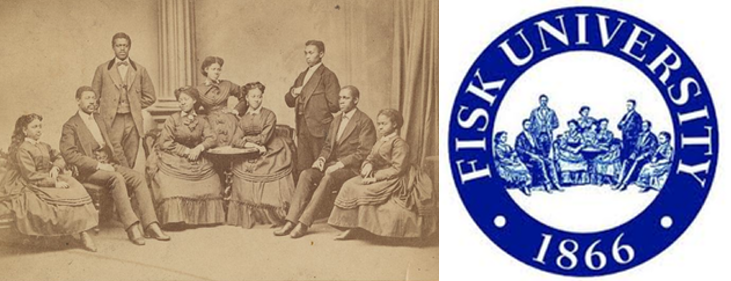

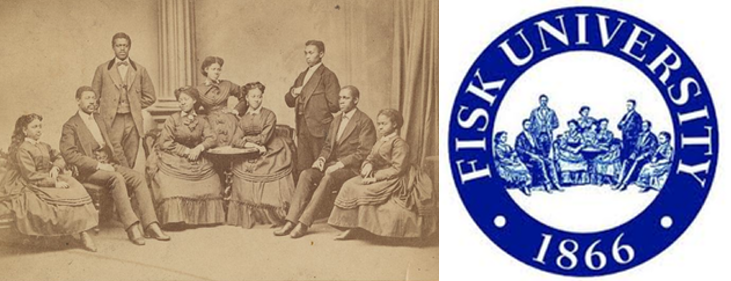

Founded in 1866 by the American Missionary Association, Fisk University in Nashville, TN became the United States’ first “black” university. Formed in the Reconstruction era of America, Fisk was a school that would “offer a liberal arts education to young men and women irrespective of color.” Fisk University, however, did not avoid hardships as the institution struggled to survive past its infancy. Within five years, the school found itself in dire need for financial support. So what does any university do when they need to make money? They form a touring ensemble.

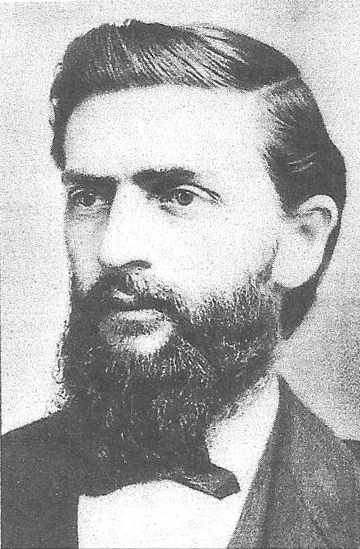

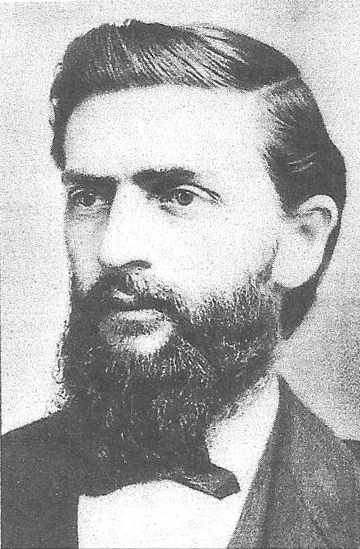

George L. White was originally hired to serve as Fisk’s treasurer, but also found his way into the music classroom. Noticing the institution’s need for income, the treasurer turned music professor also became the school’s first director of choirs. In 1871, White established a choir of freed slaves that he later named the Jubilee Singers. The choir’s purpose was to go and tour the country to raise money for the university. Ella Shepard, the ensemble’s pianist, described the intentions and drive of White was “to sing the money out of the hearts and pockets of the people,” and with that, on October 6, 1871, the choir left Nashville on their first benefit concert tour of the Midwest.

George L. White was originally hired to serve as Fisk’s treasurer, but also found his way into the music classroom. Noticing the institution’s need for income, the treasurer turned music professor also became the school’s first director of choirs. In 1871, White established a choir of freed slaves that he later named the Jubilee Singers. The choir’s purpose was to go and tour the country to raise money for the university. Ella Shepard, the ensemble’s pianist, described the intentions and drive of White was “to sing the money out of the hearts and pockets of the people,” and with that, on October 6, 1871, the choir left Nashville on their first benefit concert tour of the Midwest.

Long story short, the seven month tour was a resounding success. The ensemble was able to return to Nashville with $20,000 to be put into the institution. With the profit of their first tour, Fisk University was able to build it’s first permanent campus building, which was named Jubilee Hall and still serves the university to this day. So what exactly did the Jubilee Singers do to make their tour so successful? Simply put, they sang what they knew and what the people wanted to hear.

able to return to Nashville with $20,000 to be put into the institution. With the profit of their first tour, Fisk University was able to build it’s first permanent campus building, which was named Jubilee Hall and still serves the university to this day. So what exactly did the Jubilee Singers do to make their tour so successful? Simply put, they sang what they knew and what the people wanted to hear.

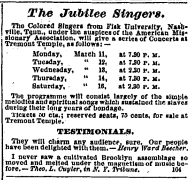

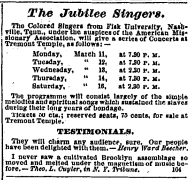

According to an article published in the Oneida Circular, the praise of the ensemble is simply “remarkable.” The singers did not have “superior talent” and though “they  are capable of singing ‘popular music’,” that had nothing to do with their success. What consistently worked for the ensemble was to defer to their “native, religious songs.” Described in one concert advertisement as the “simple melodies and spiritual songs which sustained the slaves during their long years of bondage,” the music of the Jubilee Singers captivated audiences with their novel sound and religious messages. When asked about their music by members of the public, the singers would respond that “it was never written down” and that is passed down “from generation to generation” within their families. This repertoire, coined “slave songs” would not only carry the ensemble through a successful tour, but also skyrocket them to the national and international stage.

are capable of singing ‘popular music’,” that had nothing to do with their success. What consistently worked for the ensemble was to defer to their “native, religious songs.” Described in one concert advertisement as the “simple melodies and spiritual songs which sustained the slaves during their long years of bondage,” the music of the Jubilee Singers captivated audiences with their novel sound and religious messages. When asked about their music by members of the public, the singers would respond that “it was never written down” and that is passed down “from generation to generation” within their families. This repertoire, coined “slave songs” would not only carry the ensemble through a successful tour, but also skyrocket them to the national and international stage.

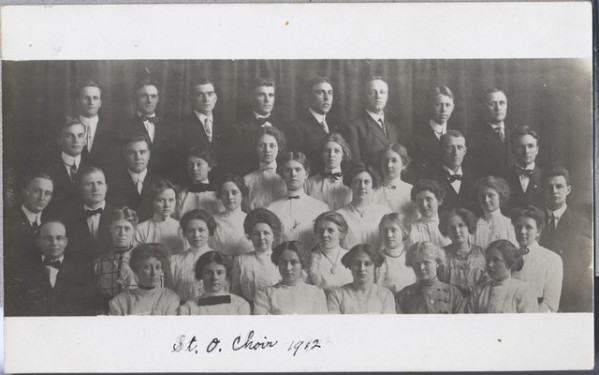

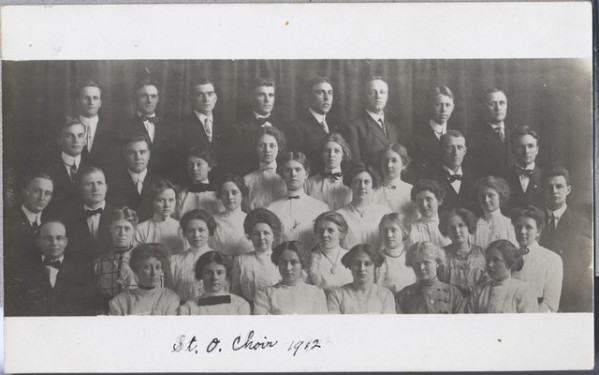

The concept of a touring ensemble is not exactly new. Here at St. Olaf College, we too have a touring choral ensemble of our own. Under the direction of Dr. Anton Armstrong, the St. Olaf Choir tours annually across the country and occasionally around the globe. Known for their refined tone and lyric sense of line, the St. Olaf Choir is a night-and-day comparison to the Jubilee Singers. Even though their musical styles contrast greatly, their underlying reasonings for going on national and international tours are quite similar: to spread their music and to collect revenue for their sponsoring institutions. Founded 40 years after the Jubilee Singers in 1912, the St. Olaf Choir and their director F. Melius Christiansen took their first major tour in 1920 to the East coast and had a similar result to the Fisk musicians, bringing in a healthy sum of revenue for the college and even established a fund to construct the first official music hall on campus. What is particularly interesting is that both choirs had similar repertoire at the commencement of their tours. Classical choral music was to be the highlight of the Jubilee Singers program, but the hesitantly had to switch to singing their people’s history on stage in order to raise the necessary funds. Both ensembles had hugely successful tours singing what the audience wanted to hear, but is that necessarily right?

The concept of a touring ensemble is not exactly new. Here at St. Olaf College, we too have a touring choral ensemble of our own. Under the direction of Dr. Anton Armstrong, the St. Olaf Choir tours annually across the country and occasionally around the globe. Known for their refined tone and lyric sense of line, the St. Olaf Choir is a night-and-day comparison to the Jubilee Singers. Even though their musical styles contrast greatly, their underlying reasonings for going on national and international tours are quite similar: to spread their music and to collect revenue for their sponsoring institutions. Founded 40 years after the Jubilee Singers in 1912, the St. Olaf Choir and their director F. Melius Christiansen took their first major tour in 1920 to the East coast and had a similar result to the Fisk musicians, bringing in a healthy sum of revenue for the college and even established a fund to construct the first official music hall on campus. What is particularly interesting is that both choirs had similar repertoire at the commencement of their tours. Classical choral music was to be the highlight of the Jubilee Singers program, but the hesitantly had to switch to singing their people’s history on stage in order to raise the necessary funds. Both ensembles had hugely successful tours singing what the audience wanted to hear, but is that necessarily right?

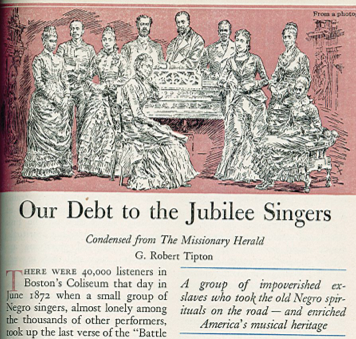

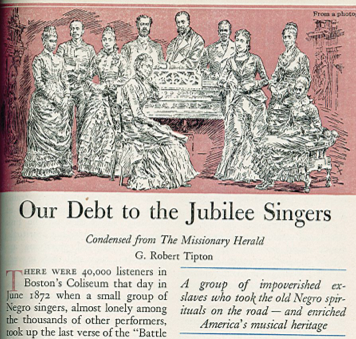

Regardless of your viewpoint on the ethics of choral repertoire when it comes to “selling” sound, the Fisk University Jubilee Singers have surely made their mark on our country’s history. More than 75 years after the Jubilee Singers inaugural tour, G. Robert Tipton wrote an article for The Missionary Herald in 1947, which was later re-published in Reader’s Digest in 1949, titled “Our Debt to the Jubilee Singers.” The article goes through a brief history of the ensemble from their establishment through their first European tour, but what I found most interesting was the summary sentence provided on the front page of the article. Tipton writes that the Jubilee Singers are “a group of impoverished ex-slaves who took the old Negro spirituals on the road – and enriched America’s musical heritage.” There is no doubt that the work of the Fisk University Jubilee Singers has not only enriched our nation’s musical antiquity, but quite possibly assisted in the preservation of the “slave song” genre that is so deeply rooted in America’s history.

Regardless of your viewpoint on the ethics of choral repertoire when it comes to “selling” sound, the Fisk University Jubilee Singers have surely made their mark on our country’s history. More than 75 years after the Jubilee Singers inaugural tour, G. Robert Tipton wrote an article for The Missionary Herald in 1947, which was later re-published in Reader’s Digest in 1949, titled “Our Debt to the Jubilee Singers.” The article goes through a brief history of the ensemble from their establishment through their first European tour, but what I found most interesting was the summary sentence provided on the front page of the article. Tipton writes that the Jubilee Singers are “a group of impoverished ex-slaves who took the old Negro spirituals on the road – and enriched America’s musical heritage.” There is no doubt that the work of the Fisk University Jubilee Singers has not only enriched our nation’s musical antiquity, but quite possibly assisted in the preservation of the “slave song” genre that is so deeply rooted in America’s history.

Sources:

TIPTON, G. Robert. 1949. “Our debt to the Jubilee singers.” Reader’s Digest 54, 95-97. Readers’ Guide Retrospective: 1890-1982 (H.W. Wilson), EBSCOhost (accessed February 19, 2015).

Advertisement 18 — no title. 1872. Zion’s Herald (1868-1910). Mar 14, http://search.proquest.com/docview/127336562?accountid=351 (accessed February 20, 2015).

H, W. B. 1872. THE JUBILEE SINGERS. Oneida Circular (1871-1876). Apr 15, http://search.proquest.com/docview/137675405?accountid=351 (accessed February 20, 2015).

“Fisk Jubilee Singers – Our History.” Fisk Jubilee Singers. Accessed February 24, 2015. http://www.fiskjubileesingers.org/our_history.html.

Shaw, Joseph M. The St. Olaf Choir: A Narrative. Northfield, Minn.: St. Olaf College, 1997.

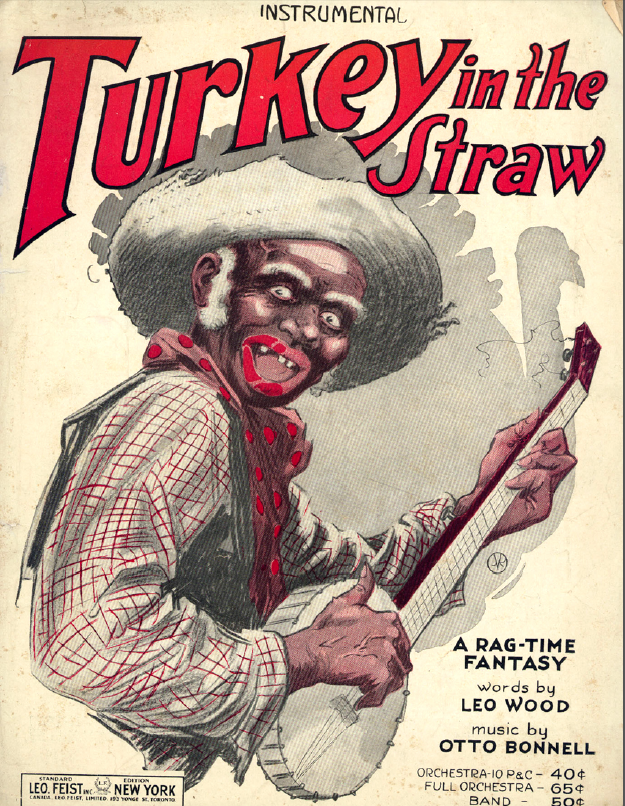

interesting challenge. Continuing the the trend of asking questions, what do these patterns mean? From what culture do they come from? How does it connect to American music?

interesting challenge. Continuing the the trend of asking questions, what do these patterns mean? From what culture do they come from? How does it connect to American music?

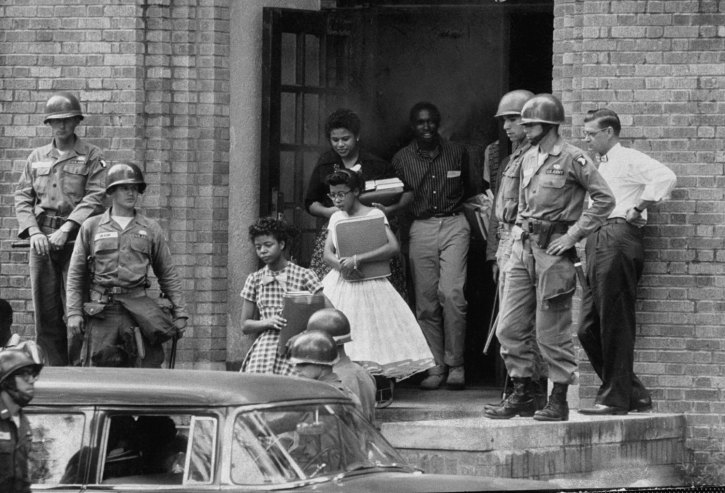

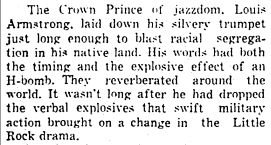

Armstrong was furious at the discrimination faced by the Little Rock Nine and did not hold back. In what was described as having the “explosive effect of an H-bomb”

Armstrong was furious at the discrimination faced by the Little Rock Nine and did not hold back. In what was described as having the “explosive effect of an H-bomb”

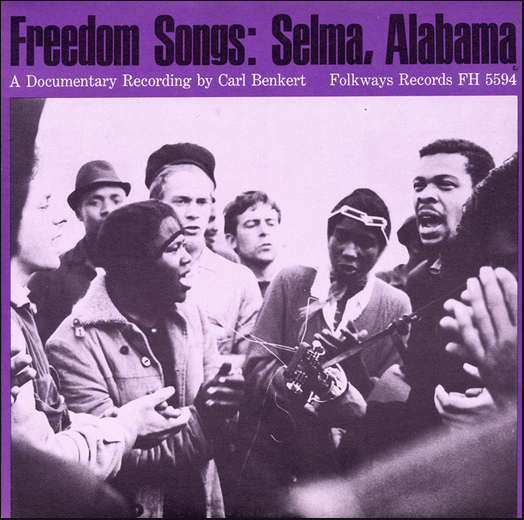

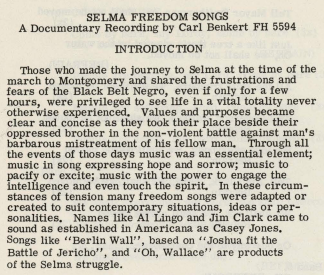

unique collection of recordings in their Smithsonian Folkways collection called “Freedom Songs: Selma, Alabama” which capture the emotional content of the march. Referred to as a “Documentary Recording,” Carl Benkert set out to preserve this moment in our nation’s history through sound. The liner notes confirm that “through all the events of those days, music was an essential element” and that the music expressed “hope and sorrow” while being able to “excite and pacify.”

unique collection of recordings in their Smithsonian Folkways collection called “Freedom Songs: Selma, Alabama” which capture the emotional content of the march. Referred to as a “Documentary Recording,” Carl Benkert set out to preserve this moment in our nation’s history through sound. The liner notes confirm that “through all the events of those days, music was an essential element” and that the music expressed “hope and sorrow” while being able to “excite and pacify.” article even specifically states that the police arrested “hymn-singing Negroes.”sup>

article even specifically states that the police arrested “hymn-singing Negroes.”sup>

George L. White was originally hired to serve as Fisk’s treasurer, but also found his way into the music classroom. Noticing the institution’s need for income, the treasurer turned music professor also became the school’s first director of choirs. In 1871, White established a choir of freed slaves that he later named the Jubilee Singers. The choir’s purpose was to go and tour the country to raise money for the university. Ella Shepard, the ensemble’s pianist, described the intentions and drive of White was “to sing the money out of the hearts and pockets of the people,” and with that, on October 6, 1871, the choir left Nashville on their first benefit concert tour of the Midwest.

George L. White was originally hired to serve as Fisk’s treasurer, but also found his way into the music classroom. Noticing the institution’s need for income, the treasurer turned music professor also became the school’s first director of choirs. In 1871, White established a choir of freed slaves that he later named the Jubilee Singers. The choir’s purpose was to go and tour the country to raise money for the university. Ella Shepard, the ensemble’s pianist, described the intentions and drive of White was “to sing the money out of the hearts and pockets of the people,” and with that, on October 6, 1871, the choir left Nashville on their first benefit concert tour of the Midwest. able to return to Nashville with $20,000 to be put into the institution. With the profit of their first tour, Fisk University was able to build it’s first permanent campus building, which was named Jubilee Hall and still serves the university to this day. So what exactly did the Jubilee Singers do to make their tour so successful? Simply put, they sang what they knew and what the people wanted to hear.

able to return to Nashville with $20,000 to be put into the institution. With the profit of their first tour, Fisk University was able to build it’s first permanent campus building, which was named Jubilee Hall and still serves the university to this day. So what exactly did the Jubilee Singers do to make their tour so successful? Simply put, they sang what they knew and what the people wanted to hear. are capable of singing ‘popular music’,” that had nothing to do with their success. What consistently worked for the ensemble was to defer to their “native, religious songs.” Described in one concert advertisement as the “simple melodies and spiritual songs which sustained the slaves during their long years of bondage,” the music of the Jubilee Singers captivated audiences with their novel sound and religious messages. When asked about their music by members of the public, the singers would respond that “it was never written down” and that is passed down “from generation to generation” within their families. This repertoire, coined “slave songs” would not only carry the ensemble through a successful tour, but also skyrocket them to the national and international stage.

are capable of singing ‘popular music’,” that had nothing to do with their success. What consistently worked for the ensemble was to defer to their “native, religious songs.” Described in one concert advertisement as the “simple melodies and spiritual songs which sustained the slaves during their long years of bondage,” the music of the Jubilee Singers captivated audiences with their novel sound and religious messages. When asked about their music by members of the public, the singers would respond that “it was never written down” and that is passed down “from generation to generation” within their families. This repertoire, coined “slave songs” would not only carry the ensemble through a successful tour, but also skyrocket them to the national and international stage.

Regardless of your viewpoint on the ethics of choral repertoire when it comes to “selling” sound, the Fisk University Jubilee Singers have surely made their mark on our country’s history. More than 75 years after the Jubilee Singers inaugural tour, G. Robert Tipton wrote an article for The Missionary Herald in 1947, which was later re-published in Reader’s Digest in 1949, titled “Our Debt to the Jubilee Singers.” The article goes through a brief history of the ensemble from their establishment through their first European tour, but what I found most interesting was the summary sentence provided on the front page of the article. Tipton writes that the Jubilee Singers are “a group of impoverished ex-slaves who took the old Negro spirituals on the road – and enriched America’s musical heritage.” There is no doubt that the work of the Fisk University Jubilee Singers has not only enriched our nation’s musical antiquity, but quite possibly assisted in the preservation of the “slave song” genre that is so deeply rooted in America’s history.

Regardless of your viewpoint on the ethics of choral repertoire when it comes to “selling” sound, the Fisk University Jubilee Singers have surely made their mark on our country’s history. More than 75 years after the Jubilee Singers inaugural tour, G. Robert Tipton wrote an article for The Missionary Herald in 1947, which was later re-published in Reader’s Digest in 1949, titled “Our Debt to the Jubilee Singers.” The article goes through a brief history of the ensemble from their establishment through their first European tour, but what I found most interesting was the summary sentence provided on the front page of the article. Tipton writes that the Jubilee Singers are “a group of impoverished ex-slaves who took the old Negro spirituals on the road – and enriched America’s musical heritage.” There is no doubt that the work of the Fisk University Jubilee Singers has not only enriched our nation’s musical antiquity, but quite possibly assisted in the preservation of the “slave song” genre that is so deeply rooted in America’s history.