In 1914, during World War I, an appeal was published in the Chicago Herald, asking American children to donate toys, sweets, and money to suffering children in Europe whose Christmases that year surely would not be as joyful. These donations traveled to Europe on the U.S.S. Jason, a Navy fuel/cargo ship, branded for this special journey as “The Christmas Ship,” or, “The Santa Claus Ship.” This appeal soon became a national movement, gathering involvement from the Red Cross and other organizations, and meriting a song to be widely performed (often by the children themselves!) to persuade children to donate gifts. This song was called “Hurrah! Hurrah for the Christmas Ship!”1 and it was written by Henry S. Sawyer, who was a composer of popular piano and vocal music at the time (see on IMSLP, his incredibly problematic “Os-Ka-Loo-Sa-Loo,” among others). The song features a cheerful melody and inspiring words. It appeals to a child’s sense of wonder at the wideness of the world and the magic of Christmas, but the lyrics also raise some issues in terms of perpetuating propaganda.

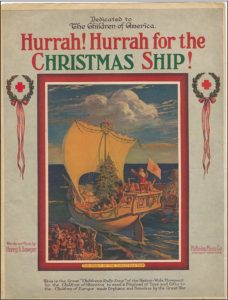

The front cover to Hurrah! Hurrah for the Christmas Ship. Notice the whimsical sailboat with Santa himself at its helm.

Henry S. Sawyer, Hurrah! Hurrah for the Christmas Ship. (Chicago, Illinois: McKinley Music Company, 1914).

The European children are referred to as “poor,” and “suffering,” implying not only their financial hardship but also poverty of spirit. The lyrics reference the “terrors” these children endure, including “fire, gun, and sword,” and homelessness. A written message on the back cover also contributes to harmful and sexist gender norms, asking girls to sew things then sell them, and asking boys to do chores and run errands for money.

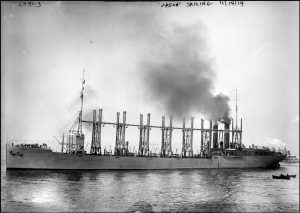

The actual “Christmas Ship,” A.K.A. The U.S.S. Jason, in November 1914. Not very whimsical, and presumably no Santa to be found.

Green, Mike. USS Jason (Fuel Ship #12) underway. Photograph. Nov 14, 1914. Library of Congress, LC-B2- 3291-3. http://www.navsource.org/archives/09/02/09021220.jpg (Accessed October 19, 2022).

However sweet the gesture and movement is, these descriptions contribute to the propaganda of wartime morale songs. While the lyrics do not directly insult enemies, the propaganda comes in the form of asking for money and instilling nationalism. If nothing else, this song trains American children that giving money during wartime is an important thing you must do for your country. Especially considering that 30 years later, many of these children will grow up to be adults during World War II, where money-pandering was a huge part of American propaganda. By asking American children to effectively be Santa Clause, this song could contribute to a superiority or savior complex that could result in nationalist ideals.

People packing boxes of gifts for the Christmas Ship ahead of its departure.

Bain News Service, Publisher. Packing for Christmas Ship. 1914. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2014697999/.

Despite the propaganda, this effort was received very well by Europe. In an article published in November 1914 in the New York Times2

, the author reports that “the citizens of Greater Plymouth [England] manifested in every possible manner the heartfelt appreciation of the 6,000,000 Christmas gifts sent by the people of the United States to the unfortunate children in the war zone.” The receiving countries hosted banquets in honor of the ship’s arrival, and telegrams were exchanged on both sides. The ship’s arrival was met with excitement and gratitude, so clearly the propaganda worked. While this movement was a sweet idea, the execution perpetuates the nationalist propaganda that runs rampant during the wartime era, indoctrinating children into the compulsion to give money and ultimately fund the war effort.

1 Henry S. Sawyer, Hurrah! Hurrah for the Christmas Ship. (Chicago, Illinois: McKinley Music Company, 1914).