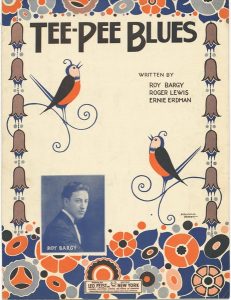

Tee-Pee Blues sheet music cover1

Tee-pee Blues1 2 is not your average song title. In fact, to a reader such as yourself, who is taking time to read blog posts for an American Music class that focuses on race, identity, and representation, such a title is at least astoundingly crass, if not downright offensive. How did someone possibly think it would be a good idea to write lyrics such as “Red man, for his canoe lonely,” set them to music that doesn’t remotely resemble Blues form, and then call it a Blues song? The answer however, as far as I am aware, is quite unsatisfying, and certainly not redeeming. Simply put, early 20th-century Americans were obsessed with exoticism (though admittedly that’s not what they called it then) and Tin Pan Alley loved nothing better than trying to capture Americans’ obsessions in music that could be marketed to them. And so, musical fluff that is more memorable for the tastelessness of its title than for its notes on the page was born. However, not all music produced by Tin Pan Alley was bad – it also produced classics such as Take Me Out to The Ball Game3. (“Classic” in this sense means something that pervaded popular culture, not to be confused with something that has an especial musical merit.)

All of this raises the question: what do we, as diligent musicologists, do about the fact that tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of Americans enjoyed and bought music like this? Do we simply frame it as a relic of times gone by, and justify our fellow Americans’ behavior as such? No! It is our duty to work to fight the cultural and economic forces that led to the production of such derogatory music, as such forces still play an incredibly active role in our lives to this very day. Spoiler: we have a lot of work to do.