After a discussion on the origins of black spirituals I was left questioning the origins of specific spirituals like “Roll Jordan, Roll”. I found, although not very surprising, that “Roll Jordan, Roll” was created by an european man by the name of Charles Wesley in the eighteenth century. He was a methodist preacher and after reading the articles by Jackson and Krehbiel, which have the goal of tackling this question of origin, I was not at all surprised that the origins of the song came from a white, protestant background. What I am left wondering is how “Roll Jordan, Roll” made it’s way to the slave south of the mid to late nineteenth century.

What I have found through my search in pursuit of answering my wonder is that the song may have been used as an effort to christianize the slaves. What I mean is the song wasn’t the sole proprietor in christianizing but was apart of a curriculum in doing so. It seems that the song had gone through an evolution and rather than being a christianizing song to the slaves, it was turned into a song of sorrow or conduit for abolitionism.

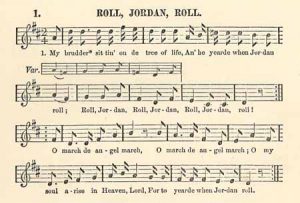

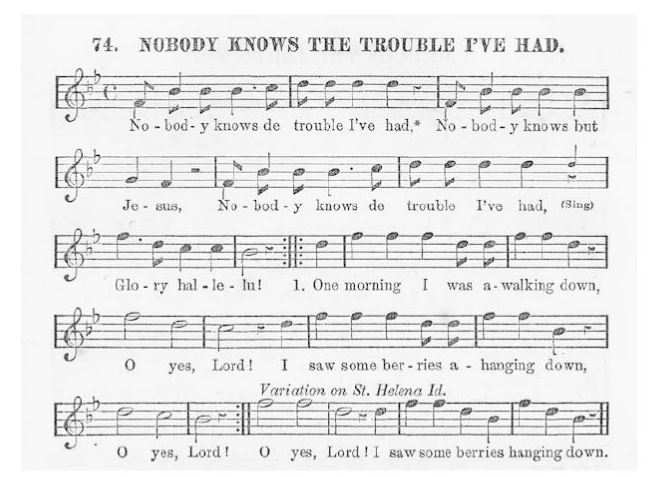

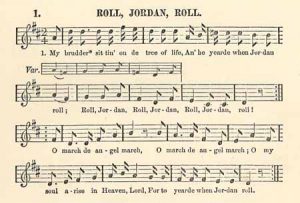

The religious allegories of the song had become a story of escaping slavery. There are many adaptations of the song, but the idea of the song being one of being delivered from slavery remains. The photo below is a documentation of one adaptation of the song. It was recorded into the

Slave Songs of the United States (1867).

Slave Songs of the United States by William Francis Allen

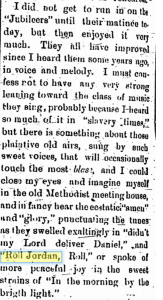

“Roll Jordan, Roll” was eventually widely accepted as a former slave song rather than methodist spiritual. Below is a excerpt from a newspaper article from 1880. Whomever wrote it acknowledges that the songs sung by the Jubilee Singers, included “Roll Jordan, Roll” originated from “slavery times”, not the old English Methodists.

I suppose for me “Roll Jordan, Roll” can not be owned by any race. It is a black spiritual as well as a Methodist hymn.

Works Cited and Consulted:

“The National Capital. Wether–Society–The Jubilee Singers.” Weekly Louisianian (New Orleans), March 20, 1880. Accessed March 20, 2018. African American Newspapers.

“Roll Jordan Roll: A Community in Song and Sound.” The Black Atlantic. March 18, 2014. Accessed March 20, 2018. https://sites.duke.edu/blackatlantic/2014/03/18/roll-jordan-roll-a-community-in-song-and-sound/.

“The River Jordan in Early African American Spirituals by Daniel L. Smith-Christopher.” River Jordan in Early African American Spirituals. Accessed March 20, 2018. http://www.bibleodyssey.org/places/related-articles/river-jordan-in-early-african-american-spirituals.

“Slave Songs of the United South.” William Francis Allen, 1830-1889, Charles Pickard Ware, 1840-1921, and Lucy McKim Garrison, 1842-1877. Slave Songs of the United States. Accessed March 20, 2018. http://docsouth.unc.edu/church/allen/allen.html#slsong1.

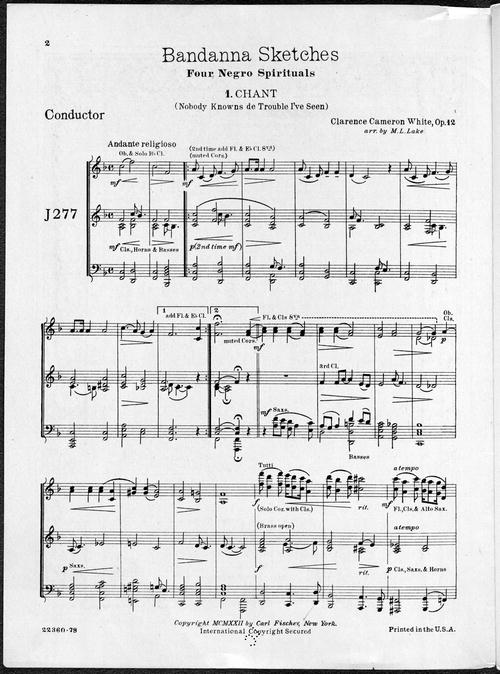

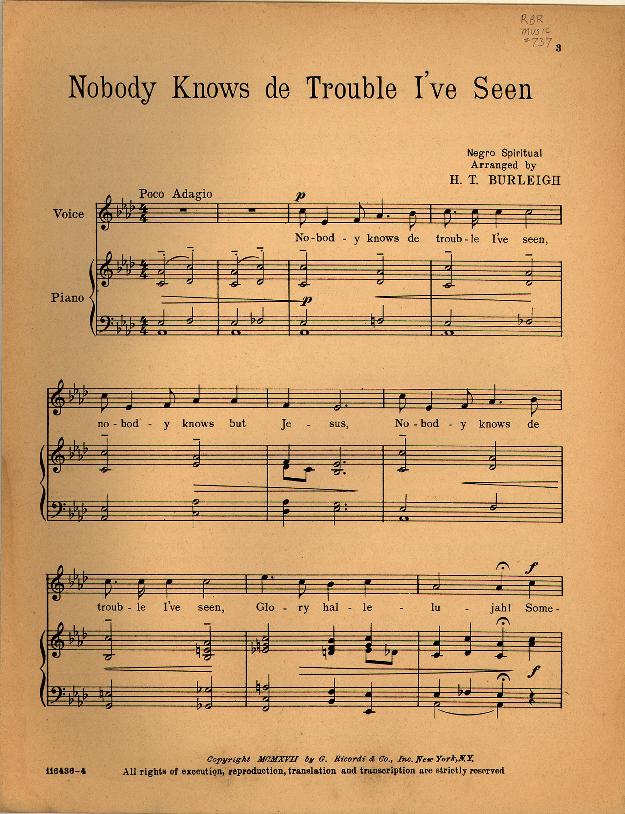

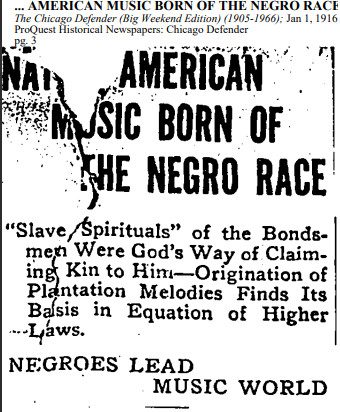

this question for an entire semester. According to The Chicago Defender, it is the song of the enslaved people that truly inspired (or birthed, in their own words) American music. The beginning of this article describes the argument that white people are the source of American music rather than that of bipoc and enslaved people. The Chicago Defender wastes no time in correcting this absurd sentiment. The author goes on to write about bipoc composers, writers and musicians. The author similarly takes a world view that all races are musical, and the truth of their being is expressed through their music. This I agree with, music expresses more than any other medium does. This expression, according to the author is one of divinity, and is an extension of God’s Way. While I don’t consider myself religious (a source of implicit bias I have) the sentiment of the author makes sense.

this question for an entire semester. According to The Chicago Defender, it is the song of the enslaved people that truly inspired (or birthed, in their own words) American music. The beginning of this article describes the argument that white people are the source of American music rather than that of bipoc and enslaved people. The Chicago Defender wastes no time in correcting this absurd sentiment. The author goes on to write about bipoc composers, writers and musicians. The author similarly takes a world view that all races are musical, and the truth of their being is expressed through their music. This I agree with, music expresses more than any other medium does. This expression, according to the author is one of divinity, and is an extension of God’s Way. While I don’t consider myself religious (a source of implicit bias I have) the sentiment of the author makes sense.