Many Americans tend to have a basic image of Chicanos/Latinos as a component of American culture that has just recently begun within the country because of how often immigration concerns are covered in today’s media. Chicano/Latino communities have existed in the United States for many years, notably in the southwest, despite the fact that immigrants and their children make up a sizeable portion of the present-day Latino population.However, many Americans appear to be ignorant of these historical occurrences and their impact in influencing the historical course of American society, much like the historical and musical effects of Chicano/Latino musicians.1

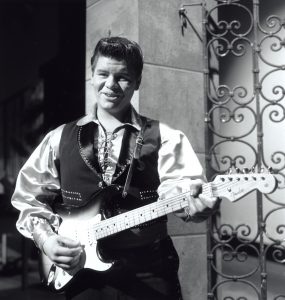

In Justin D. Garcia’s article “Ignored, But Not Forgotten: The Historical and Musical Influence of Chicano/Latino Rock ‘n’ Roll and Hip-Hop Pioneers“, Garcia discusses how Latinos/as influenced the creation and growth of rock and roll. Garcia takes a lot of time informing us about Latino performer Richie Valens. As shown in the image above2, Ritchie Valens was one of the most well-known Latino performers. Despite having a relatively short career, Ritchie Valens had a significant impact on rock ‘n’ roll with his 1958 hit “La Bamba,” which he adapted from a Mexican folk song by adding rock rhythms. At the request of his manager Bob Keane, who believed that Ricardo Valenzuela, his actual name, needed to ‘anglicize’ his name in order to boost “his marketability to white audiences in pre-civil rights 1950s America”, Valenzuela chose the stage name Ritchie Valens.1 His untimely passing in 1959, at age 17, left an absence in the Latinx music scene, but he also left behind a lot of inspiration for others to draw from. Journalist Ed Morales “At almost every turn in the history and development of rock and roll there has been a Latino influence. . . . Long before there was such a thing as Latin rock, there were Latino musicians in various rock groups. Many people today have only a vague idea of the Latin influence on rock.”3

We can look to “La Bamba”, in the video above, as a clear depiction of this cultural hybrid. The song is in verse-chorus format. Valens was initially reluctant to mix “La Bamba” with rock & roll because he was proud of his Mexican roots, but he soon agreed. Many musicians, like Selena, later imitated this kind of musical hybrid, or the blending of traditional Latin American music with rock, and it is still practiced today.1