While looking through The Chicago Defender, an African-American newspaper founded in 1905, I came across a series of articles written by Willie Belle Jones. Jones was an African-American woman who it seems worked as a musicologist for The Chicago Defender. Over the course of two years, Jones wrote a series of articles describing types of music from around the world. I could only find four of these articles, however it is implied in the article “Chinese Street Music” that Jones wrote one of these articles every week,1 although it is possible not all of these articles were about musical cultures. The range of the articles that have been preserved are from April 1929 through July 1930, however it is possible that this series extends beyond those boundaries.

In the four articles I found, Jones shares her opinions of music from China, India, Japan, Mexico, and Peru. It is unclear whether or not Jones herself traveled to these countries, or had other methods of learning about their musical traditions. These articles show a care for musical cultures around the world, while also demonstrating that racism and xenophobia permeated nearly all corners of the United States throughout the 20th century.

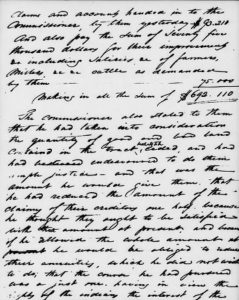

Jones, Willie Belle. “MUSIC: MUSIC IN PERU AND MEXICO.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Apr 13, 1929. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/music/docview/492217804/se-2.

In this article, Jones discusses both Peruvian music and Mexican music. Jones compares these two traditions to each other, while also comparing them to “oriental” music traditions. I think these comparisons are problematic given that all of these traditions are so different and independent of one another. Also problematic are the descriptions of these two musical traditions. Jones describes Peruvian music as “Idyllic and Pastoral” while describing Mexican music as simply “barbarous.” It is already bad to assign certain qualities to an entire country’s music, and even worse to refer to an entire tradition as “barbaric pomp.”4

Jones, Willie Belle. “MUSIC: CHINESE STREET MUSIC.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Jun 15, 1929. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/music/docview/492306389/se-2.

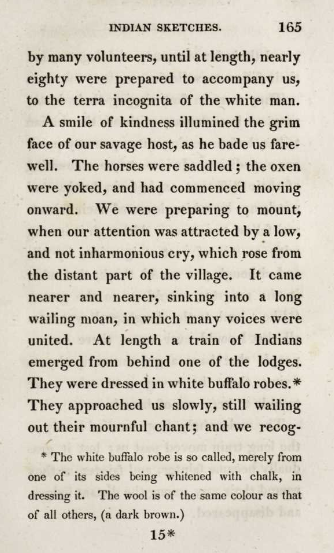

Jones seems to take a fancy to “Chinese Street Music,” however that doesn’t stop her from impressive feats of racist rhetoric throughout the article. Jones refers to Chinese workers as “coolies,” which is a slur so old and racist that I didn’t even know it existed until just now. Jones also makes fun of the variance within this musical tradition, and describes it as “purely racket” and “[not] very pleasant to the ear.” However, Jones seems enamored by the idea of having music in the streets throughout the day.1

“MUSIC: MUSIC IN JAPAN.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967),Jul 05, 1930. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/music/docview/492235829/se-2.

Jones does not dedicate too much time to the music of Japan in this three sentence long column. She simply implies it’s basically the same as China, and moves on.3 This is insidious both for its lack of care and effort to understand Japanese music, as well as its essentialization of all Asian music as roughly identical.

Jones, Willie Belle. “MUSIC: MUSIC IN INDIA.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Mar 30, 1929. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/music/docview/492230977/se-2.

In this article, Jones argues that Indian music is more pleasing than that of the other countries she has described. What is the basis for this claim? That Indian music more closely resembles European music than that of the other countries. I don’t doubt that music built on “seven tones to the octave” with characteristics similar to European music can sound more familiar to Western audiences. However, to describe this music as objectively “more pleasing” due to its proximity to western classical music is eurocentric and a problem in and of itself.2

These articles showcase that even within communities working to combat racism in the United States, racism was still internalized to the fullest extent. However, it is cool to see the interest that this community had for other musical traditions from around the world.

1 Jones, Willie Belle. “MUSIC: CHINESE STREET MUSIC.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Jun 15, 1929. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/music/docview/492306389/se-2.

2 Jones, Willie Belle. “MUSIC: MUSIC IN INDIA.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Mar 30, 1929. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/music/docview/492230977/se-2.

3 “MUSIC: MUSIC IN JAPAN.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967),Jul 05, 1930. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/music/docview/492235829/se-2.

4 Jones, Willie Belle. “MUSIC: MUSIC IN PERU AND MEXICO.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Apr 13, 1929. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/music/docview/492217804/se-2.