We have been tackling some difficult ethical issues in this class regarding how we should feel and respond to the shameful reality of minstrelsy and its related veins. One conclusion we have come to is to acknowledge the past, recognize (white) America’s shortcomings, and point ourselves and others in the direction of something better. In my research for this post, I feel I have found that something better.

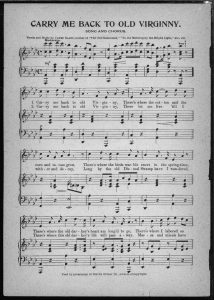

Sheet music for “Steal Away” arr. by H.T. Burleigh.

Complete sheet music here.

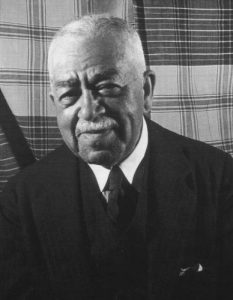

I came across the spiritual, “Steal Away,”1 the name of which I recognized as a song Viking Chorus sang during my freshman year. I found that the spiritual was arranged by Harry T. Burleigh, and reading about him was a little shining star in this (at times) depressing class. A rendition of the spiritual can be found on Youtube, among several others.

Harry Thacker Burleigh (b. 1866) is recognized as the first and among the most influential African American composers in post-Civil War America. He studied at the New York National Conservatory of Music where he became friends with Antonín Dvorák, who was the school’s director. They spent ample time together, Burleigh sharing with Dvorák the black spirituals and plantation songs that he had heard from his grandfather. Dvorák encouraged Burleigh to save these songs, to arrange them as his work.2 Thankfully, he did. “Steal Away” is one of the hundreds of pieces he arranged and composed. His most successful song is likely his arrangement of “Deep River” (1917), a song many people today recognize.3

Photograph of Harry T. Burleigh by Carl Van Vechten

In the booklet of “Negro Spirituals” from which I found “Steal Away,” one of the first pages is a single page note from Burleigh on spirituals. Similar to the descriptions of spirituals Eileen Southern provides in Antebellum Rural Life,4 Burleigh outlines them as “spontaneous outbursts of intense religious fervor, and had their origin chiefly in camp meetings, revivals and other religious exercises”. He goes on to condemn the portrayals of blacks and their music in minstrel shows, declaring that the attempted humorous mimicry of “the manner of the Negro in singing them” is a “serious misconception of their meaning and value”.5

It is my belief that, with the knowledge of the shortcomings of American culture in our hearts, we should look to and celebrate those who do not fall into the questionable traditions we have encountered. I think Harry T. Burleigh is a splendid example. Thus, I would like to end this post with the ending words of Burleigh’s note in the booklet. He speaks of that value mentioned above, the true value of spirituals.

Their worth is weakened unless they are done impressively, for through all these songs breathes a hope, a faith in the ultimate justice and brotherhood of man. The cadences of sorrow invariably turn to joy, the message is ever manifest that eventually deliverance from all that hinders and oppresses the soul will come, and man–every man–will be free.

–H.T.B.