Madame Evanti’s Custom Built Fischer Piano. Evans-Tibbs collection, Anacostia Community Museum, Smithsonian Institution, gift of the Estate of Thurlow E. Tibbs, Jr.5

Madame Evanti’s Custom Built Fischer Piano is located at the Anacostia Community Library in Washington, DC. Now if you are anything like me you might have questions like:

Who is Madame Evanti, and why is her piano special enough to be in a museum? What is the Anacostia Museum and why was it assigned for the blog posts this week?

Anacostia Museum, which opened in 1967,1 is created for and about the community of Anacostia, a neighborhood in Southeast Washington, D.C. that is home to many influential artists and leaders. The museum does feature many important artifacts from the Anacostia community but has also branched out to incorporate a larger diaspora.

The goal of the museum is to interpret and celebrate African American history and culture.2 This means incorporating not only locally and regionally found expositions, but nationally and internationally as well. Because of this global and local lens, the museum has impressive features on the family archives of 19th-century African American locals and works from black DC artists.2 This archival work is reparative documentation of history that has previously been erased from history but is now story-telling of the east-of-the-river communities in DC that will be remembered and recognized. Starting with Madame Evanti.

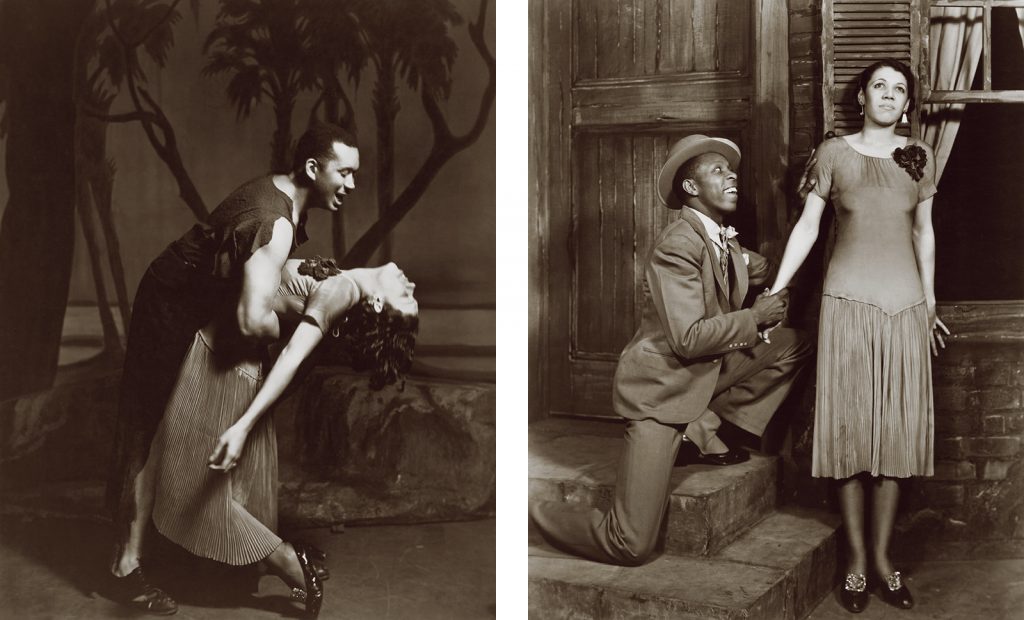

Portrait of Lillian Evanti made in Buenos Aires, Argentina, undated. Evans-Tibbs collection, Anacostia Community Museum, Smithsonian Institution, gift of the Estate of Thurlow E. Tibbs, Jr.6

Lillian Evanti is famous for being the first African American to sing in a professional European opera company.3 She was born in 1890 to a well-education and affluent African American Family in Washington D.C.. Due to her family status, she was fortunate enough to attend Howard University and graduated in 1907. She became composer, lyricist, and teacher but was limited in her professional opportunities due to discrimination. She moved to Europe and made her debut in Nice, France in 1924.4 Her success in Europe is impressive and historically significant, but it is not as heavily discussed as the great strides she afforded for the arts in America upon her interspersed returns home.

Madame Evanti was a founding member of America’s National Negro Opera Company (NNCO).4 She starred as Violetta in the opening production staging of Verdi’s La Traviata. Throughout the 1930s, Evanti advocated for the establishment of cultural center in Washington for classical and contemporary music, drama and dance. Her labor, testifying to a congressional committee in advocacy for a national performing arts center, contributed to the creation of the Kennedy Center.4

Madame Evanti is also a good-will ambassador through the State Department.3 She traveled to Latin America to perform, but her travels inspired something bigger. Evanti was also a composer. Below is a recording of one of her compositions. Her song Himno Pan-Americano is an anthem of peace dedicated to the Pan-American Union (now known as the Organization for American States).3

So much history and story-telling to be told, and it was all behind a piano.