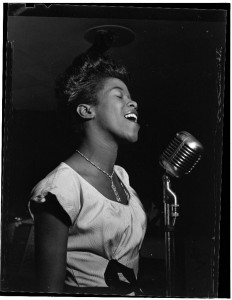

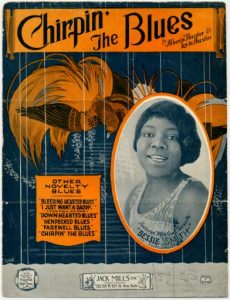

Although usually not properly credited, women have always made music, from nuns composing hymns to today’s pop icons. Blues music is no exception. Bessie Smith recorded the first ever commercial blues records in 1922, and her sales success set up that decade to be one where women dominated the genre.1 She was one of the most successful Black performing artists of her day,2 and her success marks the beginning of the genre of “race records” marketed to the African-American audience by early recording companies. Six years previous to Bessie’s first recording session, the Chicago Defender (a major Black newspaper) had begun a campaign for major record companies to record Black artists. Once the genre had taken off commercially, the paper began to feature ads for these records, including over a hundred ads for Bessie Smith’s music alone.3

The emergence of blues as a commercial music genre in the 1920s happened to coincide with the Great Migration, where thousands of Black Americans left the South to move to northern cities in search of jobs, motivated by the false promise that Northerners would be less racist. This became a predominant theme in the blues music the Defender advertised, including Smith’s music. Smith was extremely critical of the Migration in her music, which makes the paper’s fervent support for her a bit odd, since the Defender’s founder actively promoted the Great Migration.4 Mark K. Dolan argues that these ads for blues music about life “down home” in the South is the paper’s invitation for Black Americans in the North to participate in the cultural memory of the violence and pain that these songs express, and as the Migration revealed itself to be an empty promise, they became a source of shared nostalgia.

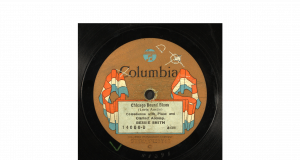

Smith’s critical perspective can be seen in the song “Chicago Bound Blues” from 1923, recorded in the same year by Ida Cox. In this song he sings about her man leaving to find a job in Chicago, leaving her behind:

“Mean old fireman, cruel engineer

Mean old fireman, cruel engineer

You took my man away and left his mama standing here.”5

In the final verse, she nails home the immense pain that the Great Migration has caused her by separating her from her man: “Red headline in tomorrow’s Defender news…’Woman dead down home with the Chicago Blues.’” Smith even directly references the Defender in her criticism of the Migration.6

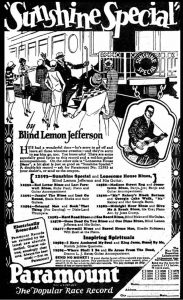

Yet, the newspaper’s ads imposed an imagined, romanticized South as the setting for all of these songs, positing it as something far away and imagined, nostalgic and yearned for, and yet still a site that is predominantly characterized by the pain and tragic themes expressed in blues music.7

Eventually, the Defender realizes the potential for the romanticization of a “lonely wayfarer” character in the Delta blues performed by Black men, and the ads for male singers’ music soon overwhelm those for female performers. The political and sexual agency found in blueswomen’s music is silenced before it even has a chance to be properly heard.

1 McGuire, Phillip. “Black Music Critics and the Classic Blues Singers.” The Black Perspective in Music 14, no. 2 (1986): 103. https://doi.org/10.2307/1214982.

2 Meckna, Michael. “Smith, Bessie.” Grove Music Online, May 24, 2022. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/display/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-90000315175.

3 Dolan, Mark K. “Extra! Chicago Defender Race Records Ads Show South from Afar.” Southern Cultures 13, no. 3 (2007): 107.

4 Dolan, 107.

5 Genius. “Chicago Bound Blues (Famous Migration Blues).” Accessed September 28, 2023. https://genius.com/Ida-cox-chicago-bound-blues-famous-migration-blues-lyrics.

Eventually, Sherman Dudley’s circuit of theaters for African American performers, the “Consolidated Circuit,” merged into the Theater Owners Bookers Association (TOBA)

Eventually, Sherman Dudley’s circuit of theaters for African American performers, the “Consolidated Circuit,” merged into the Theater Owners Bookers Association (TOBA)