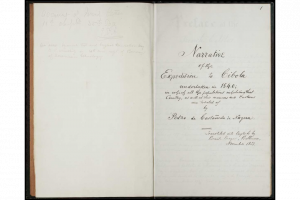

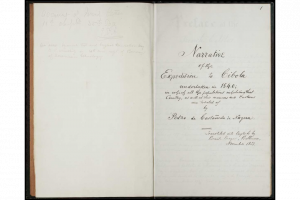

Along the border of New Mexico and Arizona one can find the Zuni people, a North American Indian tribe. Believed to be the descendants of the prehistoric Ancestral Pueblo, they have a long history of connection to the Pueblo tribe, including the involvement in the Pueblo Rebellion against the spanish. Their culture is deeply rooted in religion, spirituality, and the earth, specifically being known as the “Sun Worshippers”. Additionally the Zuni people, much like many other native tribes, utilize music in order to create a community space while completing activities like fire starting or welcoming the sunrise. The main primary source that I would like to share is a journal written by Castañeda de Nájera as he described his journey to Cibola, New Mexico. The book begins with his departure from Compostela on February 23, 1540 to Cibola. This happened to be the “poor pueblo village of the Zuni Indians”. There are also accounts of discovering as they travel America, but I will primarily focus on the Zuni tribe. Additionally, the later section of this book described the native american tribes including the making of their houses, customs, religion, agriculture, and dress. The book then ends with their unsuccessful expedition back to Mexico.

The infamous 16th century Spanish explorer Francisco Vasquez de Coronado led an important expedition in 1540 to New Spain in search of gold. Much like many other explorers of the time forced his way into many tribes including the Zuni tribe of Hawikuh, where modern New Mexico remains. This was the first discovery of native tribes for Coronado and it ultimately ended in violence as he attempted to take the town, which caused the tribe to flee their homes. This failure led to further exploration and several more battles with various tribes. As Coronado inserted himself into tribes such as the Tusayan, Triguez, and Acoma, he accounted for more and more traditions that the Native American tribes took part in, leading to the manuscript shown above.

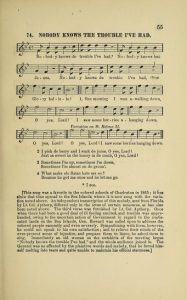

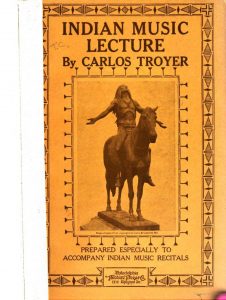

Alongside the score that I have described, attached is a book written by Carlos Troyer entitled Indian Music Lecture published in 1913. This book encapsulates Troyer’s life and experiences as he traveled various spaces in order to discover and share various tribes’ religion, government, and lifestyle. Troyer is yet another example very similar to the primary source journal shown earlier in which an outsider takes initiative to research and implement their presence on a Native Tribe; interestingly enough both Coronado and Troyer both research the Zuni Tribe.

Carlos himself is a musician born in Frankfurt in 1837 who then traveled to America at a young age and began teaching music, composing, and traveling to a variety of countries to learn and share native culture. His contact with the Zuni people occurred when he was entrusted to interpret their songs through his work in California. Instead, Troyer visited the tribe and learned of their sacred dances, ceremonies, and “traditional lore”. His goal of the trip, just like his work with other tribes like the Incas, was to give insight to mainly American and European people about indigenous culture.

While it can be said that he achieved his goal and spread awareness on the tribe’s way of life, the way in which Troyer went about entering the tribe is questionable in terms of ethics. It appears that he gained permission and was well received, but one wording in a letter at the beginning of the book by Charles Cadman claimed that he “conquered ” other tribes. Whether liked or not, it comes to reason that his privilege of power as a white man allowed him privileges to expect acceptance for researching the tribe. Lastly, there is the occasional phrasing that invokes a sense of superiority such as the title of the book which is “an address designed for reading at musical gatherings, describing the lives, customs, religions, occult practices, and the surprising musical development of the cliff dwellers of the south west”. Wording like “surprising” gives indication that little was expected of the tribe and it places indigenous culture in an othering position.

2019 Buffalo dance/Pueblo of Zuni,NM @ Sañto Ñino

Bibliography

Castañeda de Nájera, Pedro de. “Narrative of the Expedition to Cibola Undertaken in 1540

[Manuscript]: Translated into English by Brantz Mayer.” American Indian Histories and Cultures – Adam Matthew Digital. The Newberry Library, 1851. https://www.aihc.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Images/Ayer_MS_1058/4.

History.com Editors. “Francisco Vázquez De Coronado.” History.com. A&E Television

Networks, November 9, 2009. https://www.history.com/topics/exploration/francisco-vazquez-de-coronado.

Mateya. “2019 Buffalo Dance/Pueblo of Zuni,NM @ Sañto Ñino.” YouTube, YouTube, 6 Jan. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=o74Z0ZZOTEI.

Robert Stevenson. “Troyer, Carlos.” New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Oxford

University Press, 2001, https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.28481.

Stevenson, Robert. “Troyer, Carlos.” Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. Date of

access 22 Sep. 2022,

https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001

.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000028481

Troyer, Carlos, and Charles Wakefield Cadman. Indian Music Lecture: The zuñi Indians and

Their Music: An Address Designed for Reading at Musical Gatherings, Describing the

Lives, Customs, Religions, Occult Practices, and the Surprising Musical Development of

the Cliff Dwellers of the South West. Theo. Presser Co., 1913.

Frances Densmore was an accomplished woman who took on the task, given by the United States government, to record a vast amount of songs from indigenous tribes across the nation. By peering into this task shallowly, one might argue that she made a great and positive feet for the indigenous tribes she encountered. She is inherently responsible for keeping many traditions and songs from these tribes alive through her use of publications, notation, and recording cylinders. However, the method in which she took to force her presence on some of the indigenous people was one that often caused critique from her peers and scholars today.

Frances Densmore was an accomplished woman who took on the task, given by the United States government, to record a vast amount of songs from indigenous tribes across the nation. By peering into this task shallowly, one might argue that she made a great and positive feet for the indigenous tribes she encountered. She is inherently responsible for keeping many traditions and songs from these tribes alive through her use of publications, notation, and recording cylinders. However, the method in which she took to force her presence on some of the indigenous people was one that often caused critique from her peers and scholars today.  The Papago people are located in the southwest region of the United states, specifically located in the valleys of the Santa Cruz River. Called by Densmore the “desert people”, the Papago lived and recorded with Densmore in the Papago Reservation in Sells, San Xavier, and Vomari in 1920. Through Densmore’s bulletin published on the Papago, we come to learn that they are an agricultural tribe, often dedicating much of their time and resources to farming maize, beans, wheat, barley, and cotton. Interestingly Densmore shares that the Papago are “by nature and industrious people and are now finding employment in various activities incidental to the coming of the white race. For instance, many are able to make a living by cutting mesquite wood in the desert and selling it in the neighboring towns.” I wonder how “natural” this quality was of Papago, or if it was the outcome to her and the government’s push for assimilation into American society.

The Papago people are located in the southwest region of the United states, specifically located in the valleys of the Santa Cruz River. Called by Densmore the “desert people”, the Papago lived and recorded with Densmore in the Papago Reservation in Sells, San Xavier, and Vomari in 1920. Through Densmore’s bulletin published on the Papago, we come to learn that they are an agricultural tribe, often dedicating much of their time and resources to farming maize, beans, wheat, barley, and cotton. Interestingly Densmore shares that the Papago are “by nature and industrious people and are now finding employment in various activities incidental to the coming of the white race. For instance, many are able to make a living by cutting mesquite wood in the desert and selling it in the neighboring towns.” I wonder how “natural” this quality was of Papago, or if it was the outcome to her and the government’s push for assimilation into American society.