William Grant Still’s feelings on the importance of musical form could not possibly be made clearer than in his 1950 essay, The Structure of Music. He describes in detail the importance of learning the rules of musical form, and how laying out the form of a piece is integral to his composition process. However, most striking about this essay was the way that Still opens and closes by thoroughly berating composers who reject traditional musical form in favor of a modern, atonal sound.

“They believe that in order to compose, one need only find a few bizarre harmonies, string them together without thought of melody, form or sequence, and emerge with a ‘composition’ that would bring them acclaim.”

“Indeed, it is hard to detect the actual themes, since the members of this school actually scorn what we know as melody.”

“Their occasional consonant intervals are weak because of bad handling; their vaunted counterpoint is incorrect, disjointed and muddled.”

These strong words left me with one particular question for Still. Who hurt you? In her introduction to Still’s essay within the collection Readings in Black American Music, Eileen Southern mentions that he had gone through a phase of writing “experimental music” before deciding to go in a different direction. In all of his admonitions against composers who abandoned form, was Still merely repeating what critics had said about his compositions from this experimental phase? In the beginning of his essay, he insists that “faulty form is immediately apparent” to a trained listener, and that an untrained listener “will wonder why he has not been able to retain a coherent impression of what has been performed.” This sounds to me like evidence taken from personal experience.

William Grant Still did indeed compose at least two works that were on the edgy side for his time, namely From the Land of Dreams in 1924 and Levee Land in 1925. Both works were performed and immediately withdrawn after puzzled reviews from critics. He received feedback that called his compositions “curious noises,” “unprofitable to compose or listen to,” and “a slavish imitation of the noises which Edgard Varése calls compositions.”

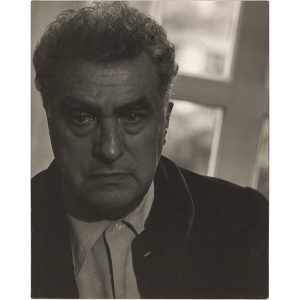

Edgard Varése was a French-American composer who worked closely with Still as one of his mentors, even called one of his most influential teachers by several sources. His music, or as he called it, “organized sound,” fits all too perfectly into the category of music criticized by Still in 1950. In the 1920s, when he was working with Still, he was producing works like this:

By the 1950s, when Still had completely rejected any kind of experimental music, Varése was still going strong.

This leads me to believe that sometime in between Still’s more experimental compositions and his complete rejection thereof, his relationship with Edgard Varése changed somehow. I’d like to imagine that there was a dramatic argument where the very purpose of musical composition was brought into question. Perhaps someday I can uncover some telltale correspondence between these two composers that will reveal the truth about their disagreement.

Sources:

“Edgard Varèse [1883-1965] – ‘Hyperprism’ [1923].” YouTube. YouTube, August 11, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FWXRAOLMq1M. “

Edgard Varèse – Déserts.” YouTube. YouTube, August 9, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1cnEo7-g880.

“Edgard Varèse.” Smithsonian Institution. Accessed December 20, 2021. https://www.si.edu/object/edgard-varese:npg_NPG.97.120.

Griffiths, Paul. “Varèse, Edgard [Edgar].” Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press, January 20, 2001. https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.ezproxy.stolaf.edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000029042?rskey=FVClre&result=2#omo-9781561592630-e-0000029042-section-3.

Murchison, Gayle, and Catherine Parsons Smith. “Still, William Grant.” Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press, January 20, 2001. https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.ezproxy.stolaf.edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000026776?rskey=PNPQkx.

Peyton, Dave. “THE MUSICAL BUNCH: THINGS IN GENERAL.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Nov 13, 1926. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/musical-bunch/docview/492099005/se-2?accountid=351.

Smith, Catherine Parsons. William Grant Still: A Study in Contradictions. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, c2000 2000. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft1h4nb0g0/

Smith, Catherine Parsons. “William Grant Still, Darker America, Africa, Symphony No. 2.” American Symphony Orchestra. American Symphony Orchestra, April 22, 2020. https://americansymphony.org/concert-notes/darker-america-1924-africa-1930symphony-no-2-1937/.

Southern, Eileen, and William Grant Still. “William Grant Still.” Essay. In Readings in Black American Music, 314–17. New York, New York: W.W. Norton, 1983.

“William Grant Still, 1895-1978.” The Library of Congress. Accessed December 20, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200186213.