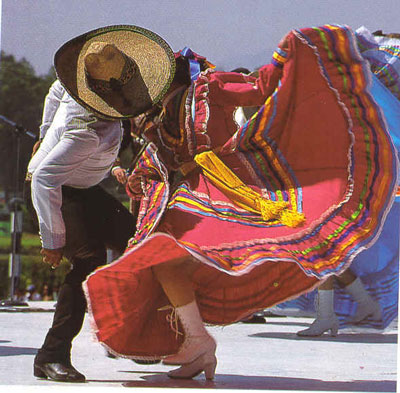

El Son Mexicano, or the Mexican song, is a type of folk music derived from classical music styles of the baroque in terms of rhythms and harmonies, but incorporated into a style of folk performances with guitar and singers. E Thomas Stanford wrote a good article on the characteristics of the style, and the history of the term and style. Stanford emphasizes the importance of dance in the style, although there is a vocabulary difference. A Danza, which is often used as a synonym for Son, denotes a more “primitive” or “raw” version of the word Baile, which is reserved for formal dances. Stanford also finds that there are elements of Baroque dance performance styles that had been lost or forgotten in other mediums, but rediscovered through the Son. It is likened to the way Madrigals have been treated in England. The Son is closer to an authentic madrigal performance than a choir singing from a stage, as both forms are intended primarily as dances.

Contrasting with this is La Canción Mexicana, another form of mexican folk music. This form is more popular in the area now known as the American Southwest and Borderlands and originated some time in the mid 19th century. Peter J Garcia wrote an encyclopedic entry for the Latino American Experience, an online database of articles related to Latino American subjects. Garcia characterizes the Canción as more emotionally driven than story driven, expressing feelings of intense sorrow, joy, grief, and gaiety. Garcia claims that the Canción reached maturity in the 1850s, causing a “golden age of mexican song.” The Canción takes its influences from Italian dramatic operas of the 18th and 19th century, using emotion as a drive rather than character motivation or storytelling. This most cleanly fits into what Americans think of as Mariachi music, although it is not mariachi. Mariachi is a distinct musical tradition with a set of specific instruments, although the two styles share some similarities.

Now that a brief history of both terms has been established, we can get into the purpose of this blog post, which is listening to some performers of both styles and contrasting them to see if there is as clear a definition as García and Stanford would have us believe.

Our first musical example comes from the Naxos audio library, and is an album called Son de Mi Tierra (song of my earth/land) by a group from Veracruz named Son de Madera. The tracks on this album are described by the group as a blending of old and new styles of Son, with a reverence for the traditions but an eye on the future. Listening to the album, which can be done here, shows some link to Baroque senses of tonality, with the solo guitar line often mixing major and minor modes in a way reminiscent of Monteverdi and Allegri. The rhythmic nature of the lines, with clear beats in the bass line, also lends itself well to dancing. The percussion (perhaps a guitar being hit, perhaps some form of drum) provides quite a bit of ornamentation around those beats, indicating a potential for some dancing ornamentation (think salsa dancing styles, with lots of hands and wardrobe accents on their dancing). The themes of this music, being a clearer story and plot driving the narrative, also indicate that this would fit into the category of a Son.

If we have found a Son, what then makes a Cancíon. The album “Con su Permisos, Señores” by Los Centzontles serves as our example here (found here). The primary difference found here is the instrumental emphasis. While the Son revolved around the stringed instruments, using the voices in conjunction, these Cancíones make heavier use of the voice. This is to such an extent that the first track begins with an acapella chorus, beginning the themes of more emotionally driven music than plot. In these pieces, an understanding can be gleaned without knowing Spanish or reading a translation.

Works Cited

García, Peter J. “Canción.” The American Mosaic: The Latino American Experience, ABC-CLIO, 2019, latinoamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/1329518. Accessed 11 Nov. 2019.

Stanford, E. Thomas. “The Mexican Son.” Yearbook of the International Folk Music Council 4 (1972): 66-86. doi:10.2307/767674.