As we began our discussions this week on Minstrelsy, I became curious to what Minstrel songs were actually about. There is obviously plenty to talk about when it comes to blackface in Minstrelsy and the performance in general, but what we seemed to have missed was a study into the content of the Minstrel music beyond its entertainment value of inflating white perceptions African-Americans.

As I searched, I found the minstrel song to the left, as sung by W. Chambers. The lyrics of the song tell of Brudder Bones going to the World’s Fair in London and getting called out of the crowd to perform on the bones. The lyrics “I mingled with the quality, I felt so awful proud” are striking as they display how Minstrel performers meant for African-Americans to feel in a crowd of “quality” people. The song also paints the image that Brudder Bones, and Minstrel performers in general, were valued primarily for their ability to put on a show, lending an eye to how performers were treated and how audiences got caught up in the pleasure of this entertainment.

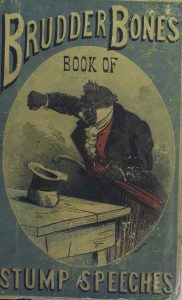

You may be wondering “who was Brudder Bones?” As I looked into the history of Minstrel performance, I found that Brudder Tambo and Brudder Bones were often the star characters of Minstrel shows. The publication below from 1868 includes a plethora of songs, skits, and speeches typical to the Brudder Bones Minstrel show.

When I think of Minstrelsy, I find it hard to appreciate it for what many claim it to be: the first indigenous, original form of American pop culture. Although there is no doubting that it was a force that brought folks together for entertainment and escape, I think raising it up as such puts a sense of pride behind an art so racially insensitive and offensive.

Sources: