Delving into jazz this week, I’ve realized that by own perception of the genre is full of contradictions. I simultaneously have a conception of jazz as a broad, far-reaching category of music and as a very specific sound. I would count myself as a peripheral consumer of jazz; I’ve listened to it intentionally a few times and been exposed to it in a vague sense for my whole life, but I’ve never studied it or fully immersed myself. In this sense, I’m probably fairly representative of the general public in my relationship to jazz; accordingly, I think many of the contradictions I find in my own perception of jazz show up in the way the general public talks about jazz.

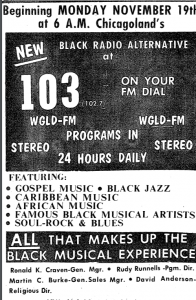

Even our use of the word jazz itself reveals this contradiction; we use “jazzy” as an adjective almost constantly. It’s odd, considering that we wouldn’t really call anything “classical-y,” “rock-y,” or “country-y.” Usually, syncopation, a swing, a little dissonance, and some blue notes are what prompt us to label a music as “jazzy.” In this way, we have some very specific sounds that we think constitute jazz. Many early critics of jazz, such as Anne Shaw Faulkner and Frank Damrosch, found that these very characteristics of jazz were what made it “primitive,” “vulgar,” and even “evil.”1 I am more inclined to agree with Langston Hughes and Dave Peyton, who see jazz’s structure, style, and sound as enabling freedom of expression.2 It is this very quality that I suspect allows the span of musics that are considered jazz to be so vasts. This span is excellently illustrated just by the Wikipedia page “List of jazz genres,” which lists fifty-five distinct sub-genres of jazz.

My reflection on how we conceive of jazz was prompted by one of these sub-genres, Afro-Cuban jazz, which I stumbled upon while searching through The Latin American Experience database.The founder of the Afro-Cuban jazz genre, Chico O’Farrill, was a Cuban-born musician who is now regarded as one of the most influential figures in the forming of Latin jazz. Particularly, O’Farrill’s “Afro-Cuban Jazz Suite” fuses Afro-Cuban drumming practices, Cuban dance forms, jazz styles, and classical music form.3

Chico O’Farrill’s “Afro-Cuban Jazz Suite”

Listening even just to the first track, “Cancion,” we can hear the typical call and response solo style of jazz, the intense rhythmic drumming in Afro-Cuban style, the syncopation and melodic lines of a traditional Cuban “Cancion,” and the dissonant, sharp chords typical of big bang jazz. I think it was precisely the contradictory nature of our conception of jazz that allowed this kind of fusion to be fully embraced as a part of the genre.

2 Robert Walser, Keeping Time: Readings in Jazz History, (New York, Oxford University Press, 1999), 55-59.

3 Gail Cueto, “Chico O’farrill”, 2019.

Works Cited:

Walser, Robert. Keeping Time: Readings in Jazz History. New York, Oxford University Press, 1999.