The music of New York-based hip hop group Public Enemy regularly created intense criticism from mainstream audiences. The uncensored, sometimes vile lyrics explicitly challenge social systems and raise awareness of race relations in the 1980s and 90s. One of the group’s most well known songs, “Fight the Power” is famous for addressing racism in a post-Civil Rights society. The video criticizes the peaceful protests of the MLK era and, instead, urges people of color to loudly defend their rights, sometimes at any cost. The video, and Public Enemy’s music and politics more broadly, were widely successful and, at the same time, widely controversial. Ethnomusicologist Robert Walser quotes the group’s frontman, Chuck D, saying that his “job is to write shocking lyrics that will wake people up.”[1] This idea is evident in any analysis of Chuck D’s interviews or lyrics, sometimes going so far as to pit black artists against each other. In my search for primary source material for this post, I came across one particular newspaper article that, a bit to my surprise, exemplified this perfectly.[2]

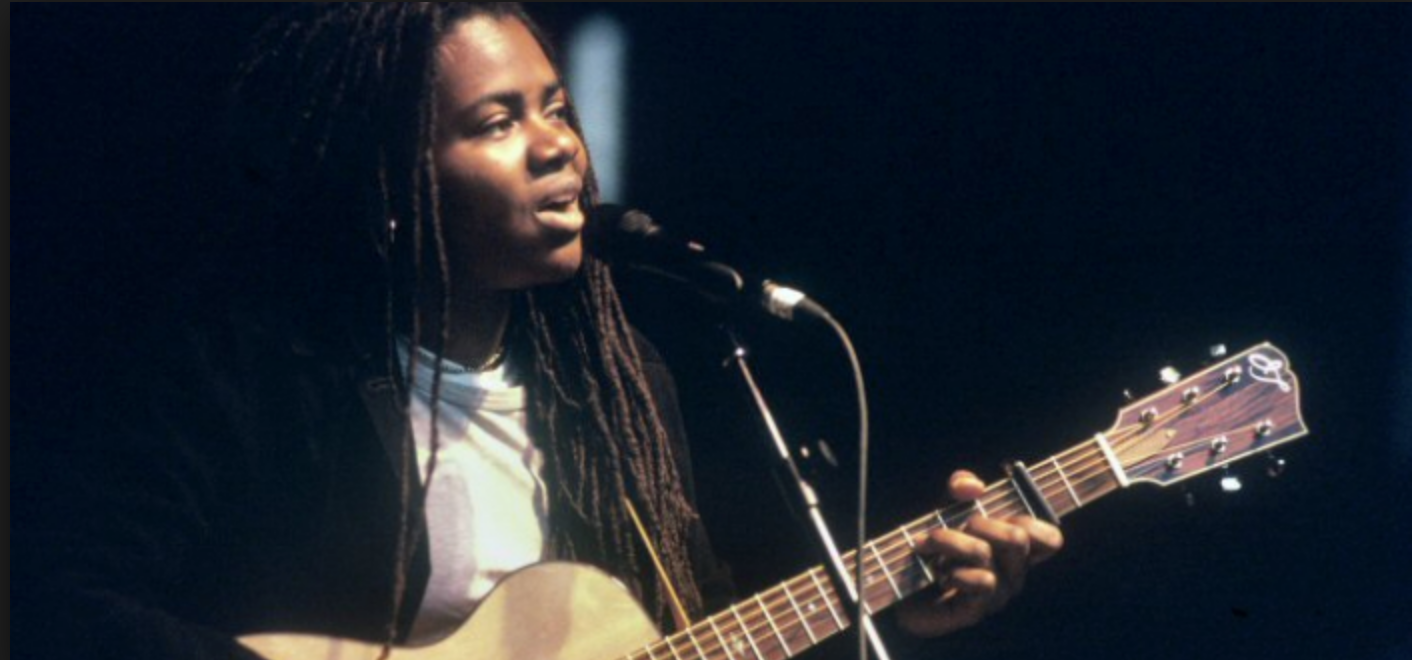

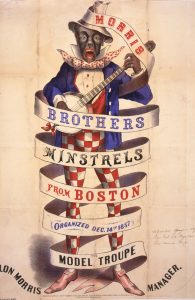

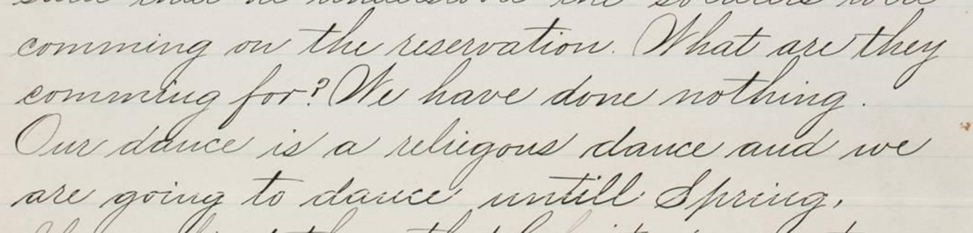

The article centers on an analysis of Tracy Chapman, an African American folk/acoustic singer, and whether her music carries the same social weight as that of Public Enemy. The author of the article highlights a 1989 quote from Chuck D, saying: “Black people cannot feel Tracy Chapman if they got beat over the head with it thirty thousand times.” The author goes on to discuss the implications of this statement and how he disagreed with the idea that there is a certain type of music that appeals to black people and can create social change. As a white student in the 21st century, I recognize that I’m in no position to comment on what constitutes an activist song for people of color in the late 20th century. But, like the author, I was struck by Chuck D’s assertion that there might be a right way to create social change through music. What is it about hip-hop that makes Chuck D think that’s the only music that can appeal to black people? Conversely, what is it about Chapman’s music that makes certain hip-hop artists skeptical of its merit?

Reflecting on these questions reminds me of earlier topics we’ve discussed in this course, such as the origins and authenticity of different genres. Chuck D’s comments suggest to me that he might view hip-hop as an authentically “black” genre, and therefore one of the few that’s able to reach African American listeners and become a true symbol of struggle and resistance. Along these same lines, does this also suggest that he thinks folk/acoustic music is inherently not “black,” or, more provocatively, inherently white? I certainly don’t mean to suggest that Chuck D was guilty of racializing genres, but I do think his comments pose interesting questions about the message behind the music. He suggests a very narrow definition which, the author of this article would suggest, creates more problems than it does answers.

[1] Walser, Robert. (1995). Rhythm, Rhyme, and Rhetoric in the Music of Public Enemy. Ethnomusicology: Journal of the Society for Ethnomusicology, 39(2), 193-217.

[2] Brown, Keith. “Message in the Music” Black Networking News, November 1, 1989. Accessed April 30, 2018 from the African American Historical Newspaper Collection. SQN: 12BA6659726F6850.