September 15, 1963: A bomb goes off at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. Four young African American girls are killed during church services, 14 more are injured.

September 16, 1963: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and President John F. Kennedy speak on the tragedy, each calling it cruel and charged by racial hatred and injustice.

1965: Suspects of the bombing emerge. Bobby Frank Cherry, Thomas Blanton, Robert Chambliss, and Herman Frank Cash—four members of the Ku Klux Klan. Witnesses don’t speak up and physical evidence is determined insufficient, so no charges are filed.

1976: Alabama Attorney General Bill Baxley reopens the case.

1977-now: Chambliss, Cherry, and Blanton are each eventually charged with the bombing. Chambliss and Cherry died in prison; Blanton was denied parole in 2016. Cash dies without being formally charged.

However, this timeline is missing an event not typically added to timelines of the Birmingham bombing.

November 18, 1963: Jazz performer, John Coltrane, records “Alabama” which, although never verbally confirmed by Coltrane, is known as a musical eulogy for the victims of Birmingham.

The song features a melancholy melody, a much slower tempo than many of Coltrane’s songs, and a hauntingly sorrowful tone from Coltrane’s saxophone. These aspects not only capture the tragedy and sorrow of the Birmingham event, but of the human injustice that ignited the civil rights movement.

It is said that Coltrane was motivated by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s eulogy for the girls. This video, featuring King’s eulogy, also shows clips from the aftermath of the Charleston church shooting from 2015, which has evocative parallels to the 1963 Birmingham bombing:

In his eulogy, King states, “These children, unoffending, innocent and beautiful, were the victims of one of the most vicious and tragic crimes ever perpetrated against humanity…They did not die in vain. God still has a way of bringing good out of evil.”

Jazz can be something joyful. It can be songs like “Sing, Sing, Sing” by Benny Goodman, it can be music that dozens dance to at weddings and in bars. But it can also be something politically motivated and inspired. “Alabama” was a source of solace for many individuals shaken by the tragedy; the rawness of the song shows the devastating nature of the bombing, but also the tragedy behind all African American lives lost during the Civil Rights Movement. Coltrane, a black musician, used what he knew best to make an impact on the Movement – music.

“Alabama,” among other politically motivated songs, remains known as an anthem of a kind for the Civil Rights Movement. Not an anthem that was sung during protests or at speeches by Civil Rights leaders, but that was heard on the radio and sparked a remembrance for the four girls who lost their lives in Birmingham in 1963.

Bibliography:

“1963 Birmingham Church Bombing Fast Facts.” CNN.com. https://www.cnn.com/2013/06/13/us/1963-birmingham-church-bombing-fast-facts/index.html (accessed November 8, 2019).

A John Coltrane Retrospective: The Impulse Years. Conducted by Eric Dolphy. Recorded November 10, 1998. Universal Music, 1998, Streaming Audio. https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Crecorded_cd%7C694615.

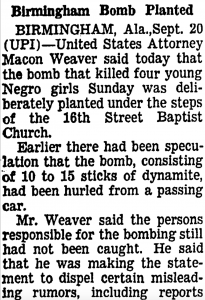

“Birmingham Bomb Planted.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Sep 21, 1963. https://search.proquest.com/docview/116602072?accountid=351.

“MLK’s 1963 eulogy after the Birmingham church bombing.” YouTube Video, 2:26. “CBS Evening News,” June 15, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iKxb0FuFlTA

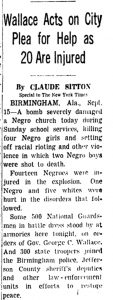

Sitton ,Claude, “Birmingham Bomb Kills Four Negro Girls” New York Times (1923-Current File), Sep 16, 1963. https://search.proquest.com/docview/116339790?accountid=351.

“The Story Behind “Alabama” by John Coltrane.” The Music Aficionado. https://musicaficionado.blog/2016/04/14/alabama-by-john-coltrane/ (accessed November 8, 2019).