Program notes from Frank Ticheli’s “An American Elegy” 1999

In April of 1999, the nation stood still as they witnessed the tragedy that was the Columbine High School Massacre. Everyone experienced a collective feeling of anger, sorrow, and grief as they watched the news in horror. Throughout the country, people could not comprehend what they had seen, and many wanted to do whatever they could to help Columbine High School. One of these groups was the University of Colorado’s Alpha Iota Chapter of Kappa Kappa Psi, a nationwide fraternity for college band members. The Alpha Iota Chapter decided to reach out to world-renowned band composer Frank Ticheli to commission a piece in honor of all those affected by that tragic day.

Frank Ticheli was honored when he was approached by the chapter and knew that he needed to write something special to commemorate those who lost their lives. Ticheli in his program notes describes how the main melody of the work came to him in a dream. Once he had the main melody, the rest of the work came together in around two weeks. Ticheli continues to describe the work in his program notes, saying,

An American Elegy is, above all, an expression of hope. It was composed in memory of those who lost their lives at Columbine High School on April 20, 1999, and to honor the survivors. It is offered as a tribute to their great strength and courage in the face of terrible tragedy.

Ticheli uses multiple pages at the beginning of the score to go into detail about each section of the work. He gives specific directions on how different sections of the piece should feel, as well as the emotions he wanted to portray while writing the piece.

All of the emotion that was put into this work becomes very apparent with just one listen of the piece. The music never tries to make a statement, which has become a theme in more recent memorial pieces, especially those about school shootings. The music focuses solely on being a memorial for all those who lost their lives, and in my opinion, does so to near perfection. The piece slowly builds up, seemingly going through every stage of grief in just 10 short minutes. The piece finally reaches its climax at around 7:00 minutes in, using the brass to play the Columbine alma matter. After this fanfare moment from the brass, the instrumentation completely dies out, leaving just an offstage trumpet solo that rings over the venue. This moment is the emotional heart of the work and portrays so much emotion without ever even needing to see the soloist.

Overall, this piece is one of the most influential pieces in all of the wind-band literature and is a beautiful tribute to those who lost so much. I want to leave this post off with one final quote from the program notes, as I feel it perfectly encapsulates the importance of this work.

I hope the work can also serve as one reminder of how fragile and precious life is and how intimately connected we all are as human beings.

Frank Ticheli, An American Elegy, Manhatten Beach Music, 1999

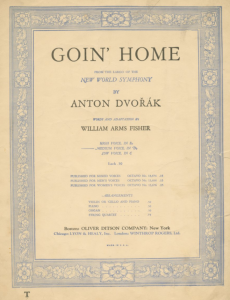

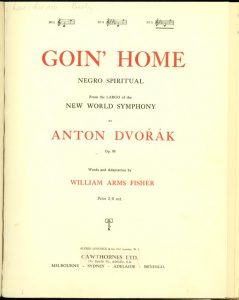

by William Arms Fisher of Anton Dvořák’s New World Symphony (No. 9, mvt II Largo, specifically). Personally, I love the symphony and have enjoyed listening to it for many years, but I can’t help but wonder now about the complicated philosophies of Dvořák and this adaptation of his work which place the work not just as a well-known music history class example to memorize, but a work that has juxtaposed good intention with possible misguided ideology.

by William Arms Fisher of Anton Dvořák’s New World Symphony (No. 9, mvt II Largo, specifically). Personally, I love the symphony and have enjoyed listening to it for many years, but I can’t help but wonder now about the complicated philosophies of Dvořák and this adaptation of his work which place the work not just as a well-known music history class example to memorize, but a work that has juxtaposed good intention with possible misguided ideology.