During my search through the American West archive, I found a scan of a rare book which exhibits early features of ethnographic analysis and contribution to literature. This book, written by a white man, is an interesting and complicated portrayal of events that occurred in the tribes he lived with. However, I think that despite its problematic and complicated nature, this mostly first-hand account of events can shed light on important aspects of certain tribe’s cultures. Specifically, I will analyze his account of two chiefs singing a “death-song” before entering into a battle in which they knew they would die.

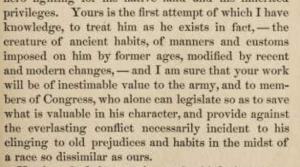

In 1910, James McLaughlin, who had been living among the Native American Tribes for 38 years, wrote of his experiences with the native peoples. His book, My Friend the Indian, is an ethnographic account of his time spent with the Native American tribes from “Standing Rock, North Dakota to Round Valley, California.” In the preface to his book, he notes that he tries to give the Indian account for events that transpired during his time with the native people. He explicitly notes that he hopes that his account does not come across as a white account, but as a native account.

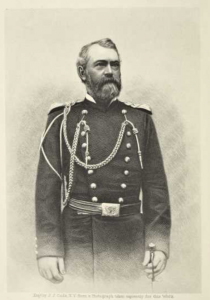

picture of Two Moons, one of the Cheyenne Chiefs who died in McLaughlin’s account

While I doubt anyone would ever actually consider it a native account, it does bring into question the status of the author, and therefore, his trustworthiness. This author was obviously not native, but he did live among them for nearly 40 years… I would not qualify him as a native, but he isn’t so much an outsider, either. As a non-member participant, ethnographers are, in a Nick Carroway from Gatsby-esque way, both “within and without.”

So, how trustworthy can they be? I believe this account is fairly trustworthy, for a couple of reasons.

In contrast to the people who wrote their first impressions of limited encounters with Native Americans in the 1600’s, McLaughlin shows finesse and respect for the culture of the people. While some people in the late 19th century began a new movement of acknowledging the native presence in the US, much of this does so with a “vanishing culture” hermeneutical lense.

McLaughlin writes with almost the opposite of the “vanishing Indian” idea – he wants to preserve the culture it in its true form and acknowledges that the culture is still alive, still a contributing, oppositional force, rather than a passive, nostalgic issue of the past, as mentioned in Blim’s article. Additionally, he does not shy away from calling out the problematic people who have decided to ignore the way that their colonizing culture snuffed out many people of a culture that was just as valuable.

Specifically, he recalls how, at one point when a Cheyenne tribe was surrounded and the chiefs asked to surrender, that the Chiefs sang their “death-song” and showed white men how natives could die honorably. The reverence with which he regards the song and actions of the Chiefs shows his respect. Additionally, his writing about the death of these two men kept their stories alive. It kept them in the minds of all who heard of them, and let people know that though these Chiefs were gone, the practices of their culture, like the death-song, lived on.

Importantly, McLaughlin notes how the chiefs sang while they fought a battle they knew they would lose. The singing here is not a passive part of the culture and history of the Cheyenne people. It is an active part of the fight which parallels the fight of the Native American people. In the “vanishing Indian” idea, the “native american problem” is finished and dealt with, and so the native people will all assimilate or die out. However, this use of music in an active fight against white men shows that even when the tribe knew they were outnumbered, they would fight till the end. Similarly, the Native American people written off by the vanishing Indian theory were not in fact slowly fading as an ember. They were energetically and vigorously fighting until the end, like a firework.

So, McLaughlin gives a fairly credible voice to people who were ignored. However, we also must remember that “determining who speaks for a culture and how much consensus is required to define a culture is only one of several problems of theory and method faced by an ethnographer of music.” (Nettl). While I do not think that McLaughlin’s account should be taken as the be all end all interpretation of the Cheyenne tribe he spoke of, I do think he genuinely wanted to use his privilege as a white author to lift up the stories of those who were marginalized.

While this can be problematic, the sincerity and intention behind his retelling (especially in light of his place in history) gives his account more positive attributes than negative. Importantly, he also set out with extreme humility and intent to tell these stories from the perspective of the native people. After living among them for almost 40 years, I think that his telling of their history comes from a place of utmost respect. His caveats at the beginning of his book – which warn the reader that he does not know everything, and that his own place is problematic – almost anticipate the criticism which we might apply to his work today.

Footnotes