Music is something that connects humanity. Across the entire world, people sing and dance together. In American history, the first people to make music across their homelands were here hundreds of years ago, and their story and history has been erased by colinization and greed of U.S. expansion. The indigenous tribes that occupied (and still occupy to some degree) these lands that we call America danced and celebrated in song and dance for thousands of years before a genocide caused their traditions to be forcibly lost and forgotten. Of the records that remain of the indigenous peoples’ music we see similarities across a large range of people who had separate communities in isolation from one another, and yet related in many aspects. The one aspect that I want to focus on is an instrument that has history in all corners of the North American Continent–the rattle.

Staff, S. F. A. (2015, November 9). Gourd Rattle, Connector of Native American Tradition. Borderlore. https://borderlore.org/gourd-rattle-connector-of-native-american-tradition/

This instrument is percussive in nature, used to accompany singing and dancing. Rattles are made out of a variety of materials. The materials used should include animal, plant and mineral components to be symbolic of the three kingdoms.1 The top of rattle, or container, can be made from a variety of natural materials, including: gourds, calabashes, turtle shells, cocoons, wood, bark, sections of animal horn, hide pouches, coconut shells, and woven fibres. 2 The handle compoentent is often made of wood, bone, or stone. The pieces inside may be seeds, clay pieces, small pebbles, or animal bones/teeth.

In part with these symbolic components used to create each instrument, the overall meaning behind the rattle as an instrument varies. Some tribes from the Eastern Woodlands region believe that rattles make the sound of creation, while some tribes from the tropical south believe they are for communication between living and spirit beings.2 For the Northwestern region, people believe that rattles represent voices from the spirit world.2 While the history and meaning behind rattles can vary from tribe to tribe, they are consistently used in ceremonies and rituals to bring peace, harmony, and healing.3

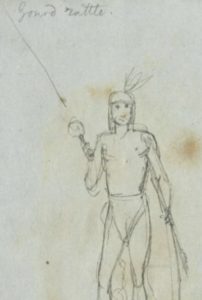

This image is of a rattle I saw at the Mahkato Wacipi. I asked the man who was playing this rattle for the moccasin game if I could take this picture. I also asked him what his rattle was made of and he told me, “I don’t know, I got it so long ago.” When I asked him to take a picture he handed me the rattle, after I took the picture and handed him his instrument back he firmly told me to shake the rattle. I shook it, and smiled at the man. He accepted my thanks for letting me see his instrument, and went back to the game. Upon further research into the history of Gourd Rattles, it is considered rude to not play a rattle, and communicates that the rattle is not nice enough or worthy of being played.4 In comparison with the rattle I was able to photograph, below is a sketch from 1851 of an American Indian man holding a gourd rattle.

[Sketchbook by F. B. Mayer, 5 of 6] – Indigenous Histories and Cultures in North America. (2024). Amdigital.co.uk. https://www.indigenoushistoriesandcultures.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Detail/sketchbook-by-f.-b.-mayer-5-of-6/7029037?item=7029060

2 “Native American Music – Musical Instruments in the Americas | Britannica.” 2019. In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/art/Native-American-music/Musical-instruments-in-the-Americas.