“Jelly Roll Morton.” 2019. Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. 2019. https://www.rockhall.com/inductees/jelly-roll-morton.

Often referred to as one of the “fathers of jazz”, Ferdinand “Jelly Roll” Morton was one of the pioneering faces of jazz to come in the early 20th century. Born in 1890 in New Orleans, Jelly Roll was at the forefront of the burgeoning genre of jazz. By age 10, he was playing in bordellos blending ragtime, minstrel music, and dance rhythms: the basis of jazz1

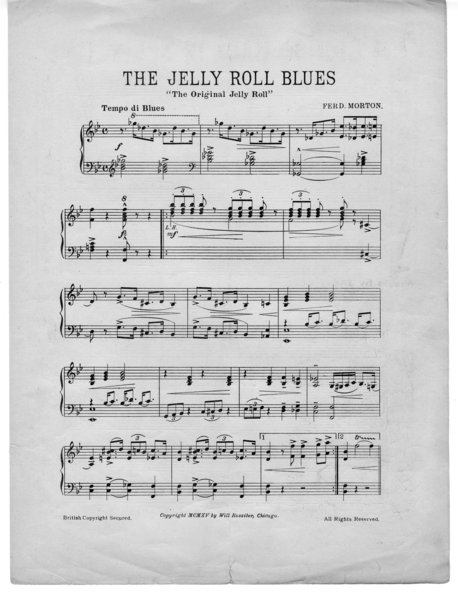

. When he left New Orleans to travel the country as a musician, he often credited himself with the creation of jazz. While this claim was, and still is, disputed by many, it is impossible to deny that his tune, “Original Jelly Roll Blues”, was the first published jazz work.

“IN Harmony: Sheet Music from Indiana.” n.d. Webapp1.Dlib.indiana.edu. Accessed October 12, 2023. https://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/metsnav/inharmony/navigate.do?oid=https://fedora.dlib.indiana.edu/fedora/get/iudl:384651/METADATA&pn=3&size=screen. Accessed via Sheet Music Consortium

Morton was far from the first to play and perform jazz, but publishing a work gave his claim serious credibility. To notate something is to is legitimize it, and that is exactly what Morton did. Many people of the time, especially white people, drew clear distinctions between jazz and classical music, high and low art, by the basis of their notation. To them, jazz was disorganized and sloppy when compared to the precise scores of orchestral works.

So notation legitimizes, but is it always in the best interest of the music? Is something lost? In Morton’s score of The Jelly Roll Blues, he consistently uses dotted sixteenth notes tied to eighth notes to allude to a swing feel, but if a musician read the ink as-is, it would still be lacking. A true swing feel is subjective, and nearly impossible to fully quantify. By being forced to notate jazz, one “establishes the objectification of subjectivity”2.

In class, we’ve discussed the difficulty of transcribing some genres from Native music to Appalachian folk music. In his article, “Country Music and the Souls of White Folk”, we see the impossibility of accurately transcribing Tommy Johnson’s “Cool Drink of Water Blues” 3. The 32nd notes and triplet rhythms in the transcription surely wasn’t the true rhythm of the song, but it was the only way to quantify and notate it. While notation helps the legitimization and dissemination of music to the masses, it may not always be necessary. For oral/aural traditions, notation and transcription removes an irreplaceable essence of the music.

1“Jelly Roll Morton – Songs, Music & Facts.” 2021. Biography. April 27, 2021. https://www.biography.com/musicians/jelly-roll-morton.

2Marian-Bălaşa, Marin. “Who Actually Needs Transcription? Notes on the Modern Rise of a Method and the Postmodern Fall of an Ideology.” The World of Music 47, no. 2 (2005): 5–29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41699643.

3Nunn, Erich. 2015. Sounding the Color Line : Music and Race in the Southern Imagination. Athens ; London: The University Of Georgia Press.

Works Cited

“Jelly Roll Morton.” 2019. Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. 2019. https://www.rockhall.com/inductees/jelly-roll-morton.

“IN Harmony: Sheet Music from Indiana.” n.d. Webapp1.Dlib.indiana.edu. Accessed October 12, 2023. https://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/metsnav/inharmony/navigate.do?oid=https://fedora.dlib.indiana.edu/fedora/get/iudl:384651/METADATA&pn=3&size=screen. Accessed via Sheet Music Consortium

“Jelly Roll Morton – Songs, Music & Facts.” 2021. Biography. April 27, 2021. https://www.biography.com/musicians/jelly-roll-morton.

Marian-Bălaşa, Marin. “Who Actually Needs Transcription? Notes on the Modern Rise of a Method and the Postmodern Fall of an Ideology.” The World of Music 47, no. 2 (2005): 5–29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41699643.

Nunn, Erich. 2015. Sounding the Color Line : Music and Race in the Southern Imagination. Athens ; London: The University Of Georgia Press.