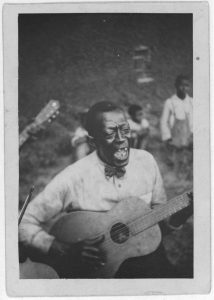

Ol’ Man River is a song that has been performed many times, analyzed, and critiqued for its lyrical depth and cultural significance. While exploring archives of the Chicago Defender, I came across a 1936 article about the film Showboat, titled: Paul Robeson Makes Film ‘Showboat’ One of Finest1.

The article offers a broad summary of the film, highlighting a few of the actors and key scenes. Notably, it praises Robeson’s vocal performance, describing his voice as:

“His deep vibrant voice ringing above the din of noise, the blare of music, the harmony of voices, fills the listener’s ears and hearts with gladness.”

The description of his vocal quality is vivid and reverent, capturing the power of Robeson’s performance. However, it glosses over the song’s lyrical content and deeper implications. Given that the article was published just three months after the film’s premiere, one might expect some discussion of the song’s meaning, especially in the context of race and labor. It simultaneously reminds us of its perceivedness during a different time.

The article does briefly touch on the presence of Black characters in the film, stating:

“Pictures portraying the South are incomplete without the richness and colorful figure of the Negro. He is an integral part of the land of toil, deeply and firmly entrenched.”

Yet this framing reduces the portrayal of Black characters to a scenic element rather than addressing their narratives or the systemic struggles they represent. The lack of critique is understandable, as the article is descriptive rather than analytical, but it shows how the significance of Ol’ Man River, a song central to the film, was overshadowed.

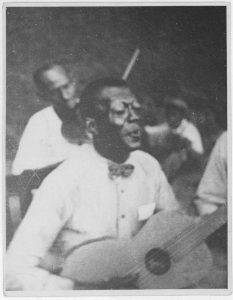

In following performances, Robeson himself addressed this oversight by altering the lyrics of Ol’ Man River to reflect his evolving understanding of Black identity and resistance2. In 1938, for example, Robeson made changes that transformed the song’s tone:

Instead of the original: “Dere’s an ol’ man called de Mississippi, / Dat’s de ol’ man that I’d like to be…”

Robeson sang: “There’s an ol’ man called the Mississippi, / That’s the ol’ man I don’t like to be…”

Similarly, he replaced: “Ah gits weary / An’ sick of tryin’; / Ah’m tired of livin’ / An’ skeered of dyin’; / But Ol’ Man River, / He jes’ keeps rolling along!”

with: “But I keeps laffin’ / Instead of cryin’; / I must keep fightin’; / Until I’m dyin’; / And Ol’ Man River, / He’ll just keep rollin’ along!”

Through these changes, Robeson reimagined the song as a declaration of perseverance and resistance.

1 Berry, Tommy. “Paul Robeson Makes Film ‘Showboat’ One of Finest.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Aug 08, 1936. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/paul-robeson-makes-film-showboat-one-finest/docview/492501551/se-2.

2 Lennox, Sara. “Reading Transnationally: The GDR and American Black Writers.” In Art Outside the Lines: New Perspectives on GDR Art Culture, edited by Elaine Kelly and Amy Wlodarski, 111–30. Brill, 2011. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctv2gjwvkc.10.