What do you think of when you think of minstrelsy?

From our contemporary lens, it’s very easy to think of minstrelsy as a horrible, racist manifestation of white supremacy. Which, for the record, it surely was. But it wasn’t just that. For many Black Americans, black minstrelsy offered a form of employment in a depressed economy, a form of control over their representation, and a training ground for later prominent figures in other forms of Black music, like blues.

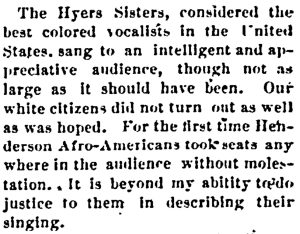

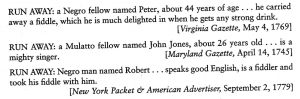

Black minstrelsy has never been universally admired, and a diversity of opinions have coexisted since its inception. As Southern writes, “The black minstrel has been much maligned by many, including members of his own race, for perpetuating the Jim Crow and Zip Coon stereotypes” (269), a statement which gets to the core struggle and contradiction of Black minstrelsy. White minstrelsy predated Black minstrelsy by several decades, and its success depended on these stereotypes. Many of the owners of Black troupes also owned white troupes. While black performers had some agency to represent themselves at least a little more authentically than white performers, Black minstrelsy still operated with many of the same expectations and for many of the same audiences. Which begs the question, what was it like for the Black performers?

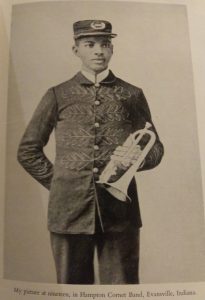

W.C. Handy

The answer, of course, is complex. Rampant white supremacy and racial violence was a fact of life for Black minstrels – Handy, a member of Mahara’s Minstrels writes in his autobiography of the lynching of a band member (43) and many other acts of racially motivated violence and harassment. But Handy, who began his career in minstrelsy and later became a major player in blues, seems to recognize the importance of Black minstrelsy, writing “Historians of the American stage have slighted the old Negro minstrels” (34).

Chick Beaman, another performer from the latter days of minstrelsy, writing for the Chicago Defender, a Black newspaper, describes almost the exact opposite contradiction . “When you

begin trouping you’re dead – theatrically – and soon forgotten” he writes, “But I love it and it’s a great life. So let the band play.” This is pretty much the reverse of Handy’s experience – Beaman valued minstrelsy as a lifestyle rather than a stepping stone in his career.

So how should we view the legacy of Black minstrelsy? Being itself fundamentally a contradiction, it’s hard to say for sure. But we do know that it was an important social, economic, and musical enterprise with lasting affects today.

Bibliography

Beaman, Chick. 1921. CHICK BEAMAN: FAMOUS MINSTREL MAN PUTS ON HIS PHILOSOPHICAL SHOES. The Chicago Defender (National edition) (1921-1967), Aug 27, 1921. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/chick-beaman/docview/491909725/se-2?accountid=351 (accessed November 15, 2021).

Handy, W.C. The Father of the Blues: An Autobiography. London. Sidgwick and Jackson, 1957.

Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans: A History. New York, NY. WW Norton Company, 1971.