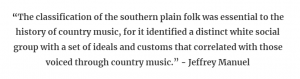

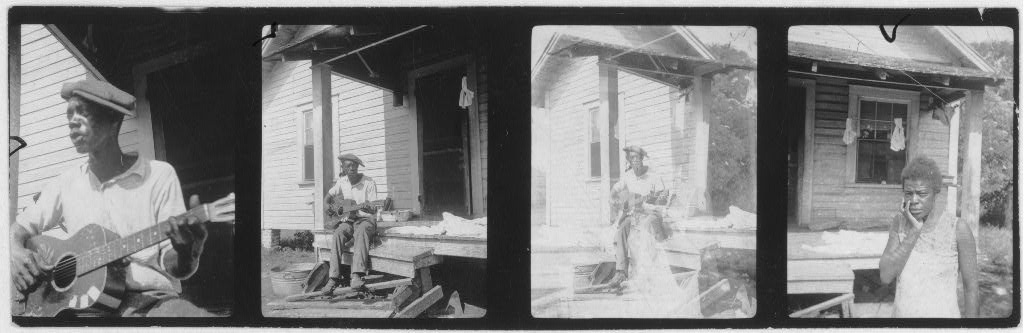

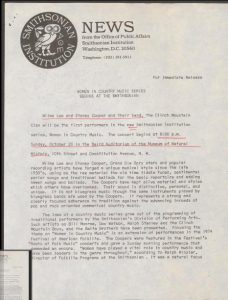

Country music has been typically shown to be stemming from white artists throughout history, but is that really true? While modern scholars have picked this stereotype apart,1 these types of cultural and ethnic separations have made making a living and gaining popularity hard for certain performers and composers. Browsing for primary sources, I first found what many would call a ‘stereotypical’ country band, named the Stoney and Wilma Lee Cooper Band. What made this even more traditional and supposedly characteristic of this type of music was that this was a married couple. Many artists at this time had some sort of family aspect to them like the Cooper Band. 2 In addition to advertising for the ‘Women in Country Music Series,’ this mid-1970s Smithsonian announcement made it clear that they wanted to showcase country music talent from women. I found that very interesting, and it’s possible that country music was patriarchal like many facets of society in the mid-1900s. This, however, is a separate research topic.

In contrast, I came across a Washington Post article about Cleveland Francis, a black man, who, in addition to being a cardiologist 3, was also a country music musician. In this 1996 article, Francis is described to have overcome barriers that made it harder for him to enter the country music scene, saying “Maybe the next African American coming along will not have to justify his position in country music.” 4

Francis, describing his experience as a black man in country music, clarifies and supports the writings of Jefferey Manuel’s “The Sound of Plain White Folk? 5” and Rhiannon Giddens’ “Community and Connection” Keynote Speech 6. Manuel’s position that commercialization of this genre led to a much more homogenous, ‘white’ view of this music led to Francis having a harder time getting into the genre and being successful. In addition, the fact that  Giddens’ calls for diversifying country and folk music speaks indirectly to the fact that this type of music is very homogenous. While other factors may be at play, it’s clear to see that Francis would have a hard time doing well in the country music genre. Despite this, he succeeded.

Giddens’ calls for diversifying country and folk music speaks indirectly to the fact that this type of music is very homogenous. While other factors may be at play, it’s clear to see that Francis would have a hard time doing well in the country music genre. Despite this, he succeeded.

- Manuel, Jeffery T., “The Sound of Plain White Folk?” Popular Music and Society, Vol 1, Oct 2008.

- “Hattie Stoneman: Raising her Children in Music.” The Birthplace of Country Music, 28 September 2017 https://birthplaceofcountrymusic.org/hattie-stoneman-raising-children-music/

- Yahr, Emily. Cleve Francis’s Unsung Story. 7July 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/arts-entertainment/2022/07/07/cleve-francis-country-music-black-opry/

- Harrington, Richard. “Cleve Francis” The Washington Post, 14 April 1996. https://www.proquest.com/docview/307971804/fulltext/77A5129B774F4C3FPQ/113?accountid=351

- Manuel, Jeffery T., “The Sound of Plain White Folk?” Popular Music and Society, Vol 1, Oct 2008.

- Povelones, Robert. Rhiannon Giddens Keynote Address. 11 February 2018. https://ibma.org/rhiannon-giddens-keynote-address-2017/