The exhibition piece, Prayer for Peace, describes Kurt Westerberg’s ‘72 De Profundis, and the images reflect a powerful response from St. Olaf students to the tragic events at Kent State and Jackson State Universities in 1970. De Profundis, which translates to “out of the depths,” was composed by Westerberg as a sophomore in the wake of these violent events, where students lost their lives amidst the turmoil of Vietnam War protests1.

The images above capture the performance of De Profundis on Capitol Hill in May 1972. This twenty-minute, three-movement composition combines vocals, instrumentals, and dance to express grief, reflection, and a longing for peace. In the program introduction, Westerberg wrote, “De Profundis is not meant to be entertaining listening nor is it a ‘hip’ version of a Biblical Psalm2.” This is important to note, given the importance of the piece’s expression.

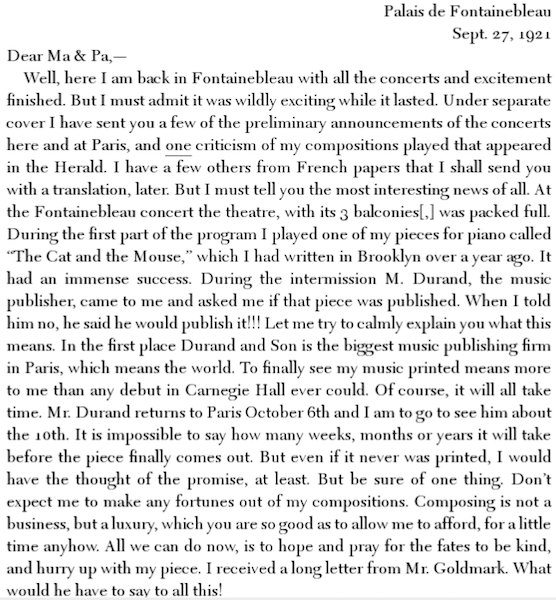

Image of Dell Grant ‘73 – St. Olaf’s First African American art major, who choreographed the sequence and performed alongside 18 others at the Capital Hill performance in 1972

Westerberg based the piece on Psalm 130, a text he encountered during a memorial service honoring the victims of the protests. The Psalm’s lines,

“If you, Lord, kept a record of sins, Lord, who could stand? But with you there is forgiveness, so that we can, with reverence, serve you3.”

form an emotional heart of De Profundis. By setting these words to music, it seems Westerberg aimed to transform sorrow and lament into a communal prayer for reconciliation, contrasting the bitterness of violence with a desire for forgiveness and healing.

While looking more into De Profundis, I came across a transcript of an interview with Westerberg in 2013. In response to his recalling of the Washington D.C. experience, he reflected on the growth of the piece and its communal contribution, stating the following:

“It was a very humbling experience to have my sophomoric work used to express a significant desire for peace and reconciliation. It was really not just my work anymore – I knew that it had grown beyond my creative input, and had impact because of the result of so many other efforts, including the [singers], musicians, and dancers4.”

As I reflect on this composition and the images, I am reminded of Nina Simone’s Mississippi Goddam, written in response to the bombing that killed four Black girls in Birmingham5. While both Westerberg and Simone address violence, their approaches differ. Simone confronts institutional racism with urgency, her music demanding justice. In contrast, Westerberg seeks solace, inviting spiritual introspection as a response to tragedy.

De Profundis, therefore, stands as a testament to music’s power to respond to violence in varied ways, whether by seeking peace, demanding change, or gathering a community in shared reflection.

1 Sauve, Jeff. “A Musical Prayer for Peace.” St. Olaf Magazine no. Winter, 2013.

2 Sauve, Jeff. “A Musical Prayer for Peace.” St. Olaf Magazine no. Winter, 2013.

3 New International Version, 2011. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm%20130&version=NIV.

4 Sauve, Jeff. “A Musical Prayer for Peace.” St. Olaf Magazine no. Winter, 2013.

5 Fields, Liz. “The Story behind Nina Simone’s Protest Song, ‘Mississippi Goddam.’” PBS, June 30, 2023. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/the-story-behind-nina-simones-protest-song-mississippi-goddam/16651/.