American-composed classical music is mostly a myth. This is because of the European teachings which influenced most of America’s largest composers. Even though there is a rich and vibrant community of folk musicians, there used to be no music besides the group of followers that Davořák had grown. One of the first major original American symphony compositions was created by a black composer William Dawson, and was premiered just under a year after Davořák’s New World Symphony premiered. Dawsons Negro Folk Symphony was a huge success and received an enormous standing ovation after its premiere in Carnegie Hall 1. William Dawson’s legacy is being a choir director at Tuskegee University 2. Dawson received his education at Tuskegee as well as founded its music department in 1931 4.

3

After the premiere of his Negro Folk Symphony, Dawson decided to focus on his career at Tuskegee University and work on its choral program as he continued to compose and arrange pieces for his choirs. During this time, he continued to push for black composers and pushed a narrative of black empowerment:

I have’ never doubted the possibilities of our music, for I feel that buried in the South is music that somebody, some day, will discover. They will make another great music out of the folksongs of the South. I feel from the bottom of my heart that it will rank one day with the music of Brahms and the Russian composers 1

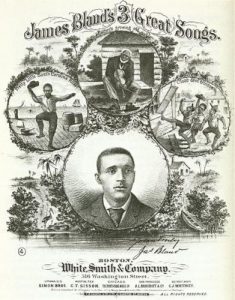

Dawson took direct inspiration from African-American spirituals and other forms of African-American music to create a symphony for the culture he knew. Another African-American composer at this time was Florence Price. Her compositions took more of a European aspect because of the composition education she received 1.

William Dawson’s symphonic career was short-lived because of the lack of further compositions 1. He has formed a lasting impact on the African-American community with the founding of Tuskegee University’s music program, which continues to benefit young musicians from all over the United States 2.

—

1 BROWN, GWYNNE KUHNER. 2012. “Whatever Happened to William Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony?” Journal of the Society for American Music 6 (4): 433–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752196312000351. Accessed October 4th, 2023

2 “Founder’s Day at Tuskegee Institute Sunday, April 4.” Capitol Plaindealer (Topeka, Kansas) 1, no. 29, April 4, 1937: PAGE EIGHT. Readex: African American Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A12ACD7F5186B1E69%40EANAAA-12C55C2E116B2EC8%402428628-12C55C2E55C768B0%407-12C55C2FA4B97D40%40Founder%2527s%2BDay%2Bat%2BTuskegee%2BInstitute%2BSunday%252C%2BApril%2B4. Accessed October 4th, 2023

3 “A TUSKEGEE SYMPHONY – Stokowski to Present Dawson’s Pioneer Work on Negro Themes.” New York Times, November 18, 1934. https://nyti.ms/3Q4Ezyb.

4 Huizenga, Tom. “Someone Finally Remembered William Dawson’s ‘Negro Folk Symphony’.” NPR, June 26, 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/deceptivecadence/2020/06/26/883011513/someone-finally-remembered-william-dawsons-negro-folk-symphony. Accessed October 8th, 2023

Horowitz, Joeseph. 2022. DovořáK’s Prophecy: And the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music. New Yourk: W.W. Norton & Company.