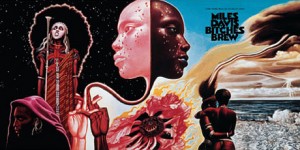

The cover of Miles Davis’ 1970 album Bitches Brew has in many ways become more iconic than the album itself.[1] Illustrated by Mati Klarwein, the mystical, Afro-centric imagery fused with psychedelic textures intensely deals with contradictory themes and ideas that were undoubtedly relevant in American political and racial culture at the time. Simultaneously, Klarwein’s contradictory images seem to capture the conflict inherent in Davis’ work throughout his career: how does a jazz giant like Davis continue to innovate without moving too far away from jazz?

His answer was to explore contradictory influences even further. Bitches Brew spearheaded the jazz-rock-fusion movement, replacing numerous components of his ensemble with electronic instruments, and rejecting traditional jazz structures in favor of the looser, long-form rock style. Davis also utilized a massive, rotating group of musicians, on numerous tracks using three keyboardists, two drummers, and two bassists.

This dichotomy was inherent to reception of the album as well. While some lauded Davis’ creativity in synthesizing what was commonly viewed as two divergent forces in American music, jazz purists thought that Davis had crossed the line and had abandoned jazz altogether. Critic Bob Rusch even went so far as to say, “this to me was not great Black music, but I cynically saw it as part and parcel of the commercial crap that was beginning to choke and bastardize the catalogs of such dependable companies as Blue Note and Prestige….” [2]

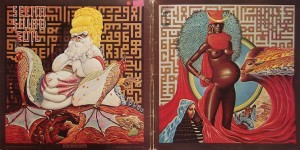

In typical Davis fashion, his response to the jazz establishment was essentially a giant middle finger: a second electronic, jazz-rock album titled Live-Evil, released in 1971.[3] As the title suggests, it featured live recordings by Davis and his personnel at the Cellar Door music club in Washington DC, most of whom also appeared on Bitches Brew. But the “live” component made up only half of the music, the rest of which was recorded in Columbia Studios. Again, we see Davis exploring dichotomies in the later stages of his career, balancing the chaotic violence of a live performance with the hyper-controlled realm of a studio session.

The cover art (again provided by Klarwein) provides a striking realization of this strange contrast. The pregnant, yet skinny black woman on the front is a perfect foil to the pale, grotesque, bloated monster on the back. As part of the ‘reflective’ nature of the album, the upper-left corner of the back says “Selim Sevad Evil”: “Miles Davis Live” backwards. John Szwed’s biography of Davis provides some clarity as to the origins and meaning of the cover art, via a quote from Klarwein:

“I was doing the picture of the pregnant woman for the cover and the day I finished, Miles called me up and said, ‘I want a picture of life on one side and evil on the other.’ And all he mentioned was a toad. Then next to me was a copy of Time Magazine which had J. Edgar Hoover on the cover, and he just looked like a toad. I told Miles I found the toad.”[4]

Ironically, Live-Evil was much more well received than Bitches Brew, despite the fact that it took what critics dislike about BB to further extremes. It was lauded for its accessibility and musical purity, even though the tracks had greater levels of electronic manipulation.

But perhaps the biggest difference between the holistic art of the vinyls is the liner notes. Bitches Brew contains a lengthy, poetic assessment of the music by Ralph J. Gleason, American music critic, founding editor of Rolling Stone magazine, and cofounder of the Monterey Jazz Festival. Its an abstract piece of writing that seemingly rejects the nitpicking of other critics concerned with such subjective notions as genre:

“so be it with the music we have called jazz and which i never knew what it was because it was so many different things to so many different people each apparently contradicting the other and one day i flashed that it was music.

that’s all, and when it was great music it was great art and it didn’t have anything at all to do with labels and who says mozart is by definition better than sonny rollins and to whom.”[3]

But when one opens the centerfold of Live-evil expecting to find another passionate defense of Davis’ innovations, they instead find a series of candid pictures of Miles.

Not concerned with critics, nor legacies, these liner notes simply say “This is me.” Or perhaps, “Me is This.”

Notes: –Both Vinyls are available in Halvorson Music Library. Bitches Brew call number: M1366.D3 B5. Live-evil call number: M1366.D3 L5.

– Entire Bitches Brew liner notes by Gleason available at: http://aln3.albumlinernotes.com/Bitches_Brew.html

[1] Davis, Miles. Bitches Brew. Columbia, 1970. LP.

[2] Rusch, Bob. Ron Wynn, ed. All Music Guide to Jazz. AllMusic. M. Erlewine, V. Bogdanov (1st ed.). San Francisco (1994): Miller Freeman Books. p. 197.

[3] Davis, Miles. Live-Evil. Columbia, 1972. LP.

[4] Szwed, John. So What: the Life of Miles Davis. Simon & Schuster; Reprint edition (January 9, 2004) p. 319.