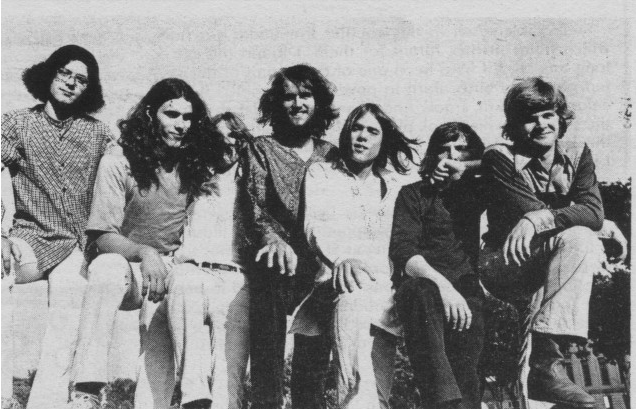

St. Olaf student, Laura Anderson, wrote in 1972 about that she met with a group of young fellows living and performing in Minneapolis. The group, previously knows as “Debb Johnson,” added several members to the group and renamed themselves “Rise and Shine.” This group had performed at St. Olaf previously. Unfortunately, Laura does not mention what music genre the group performs. However, the groups sees a future for music.

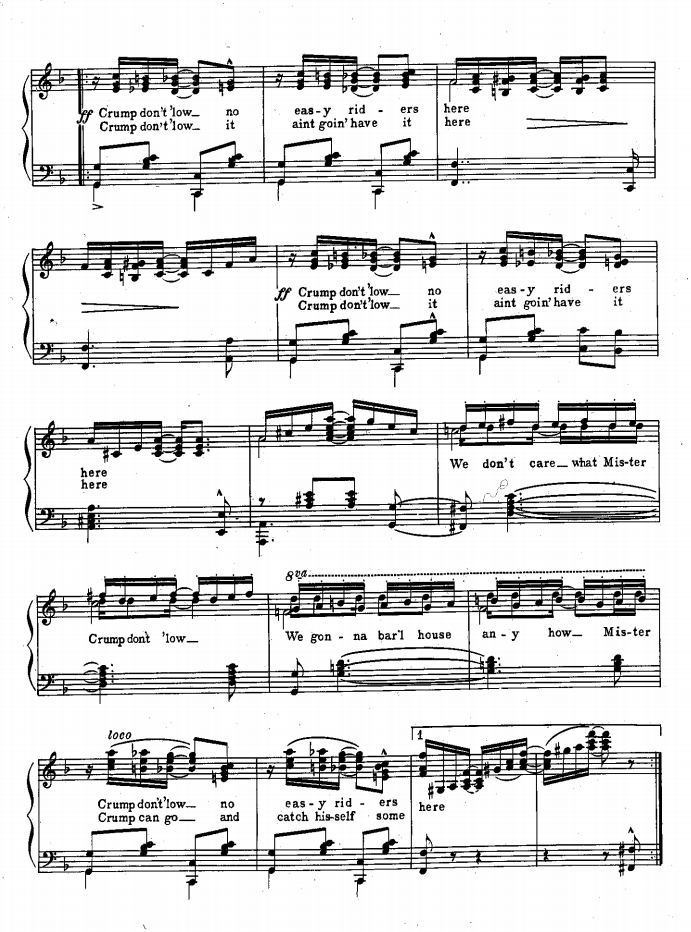

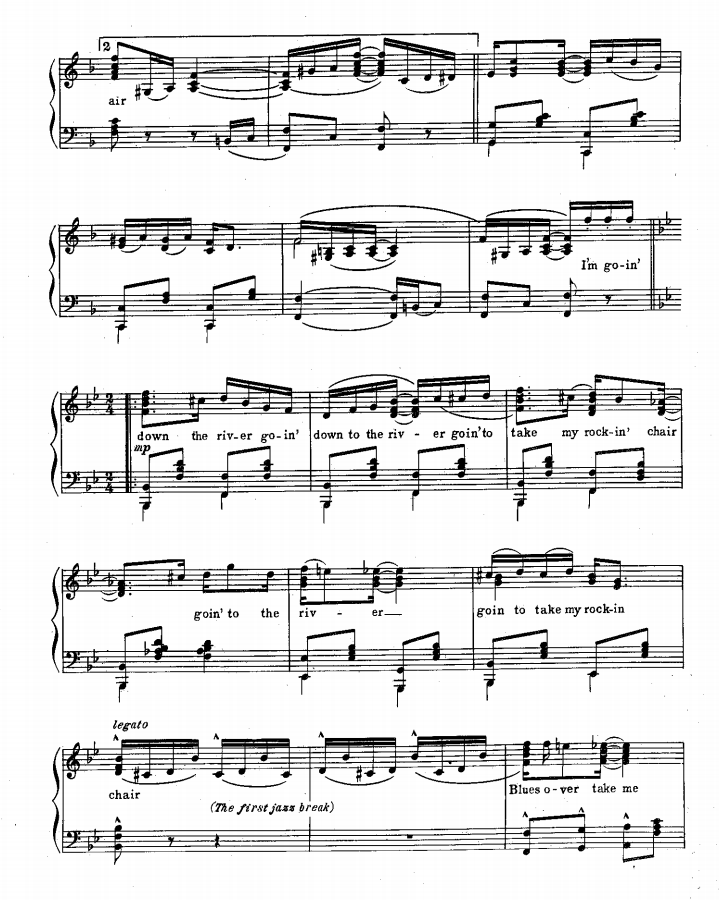

Laura reports, when she sat down with “Rise and Shine,” they arrived on the topic what is music. Laura quotes one of the band members: “The days of stoned-out boogie bands (and audiences), destruction on stage, and sloppy music are gone. People are tired of obnoxious music and egotistic performers — it’s not showmanship, it’s insanity.” Laura believes that music should consist of good musicianship. She finds loud music and quickly produced music to be disgusting. “Rise and Shine” lives to together and is constant writing and performing their own music. Their favorite groups are Shawn Phillips, the Beach Boys, and Joni Mitchell. All these uniques sounds contribute to their creative sound.

Laura’s articles shows that music, especially in the popular world, has been constantly changing, as people get bored and look for something new to entertain them. As we have seen since the 50s, music has evolved from Rock ‘n’ Roll to disco, to boy bands. Even today music seems to be evolving as people strive to create new music.