For my final blog post, I wanted to focus on W.C. Handy’s “St. Louis Blues” and how it has evolved and survived throughout the years as a jazz standard. I am particularly interested in its history because I will be performing the Bob Brookmeyer arrangement with Jazz 1 on Friday, November 22nd at 7:30 pm in the Pause Main Stage (hey, nobody said we can’t use these blog posts to advertise!)

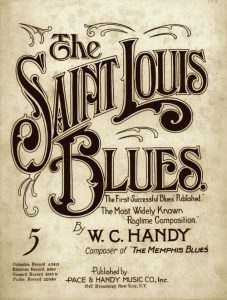

The song itself first originated from W.C. Handy’s Blues: An Anthology, which Handy used to portray blues music as folk music (even though there were some complications with classifying it as such.)[1] But nonetheless, it was touted as such by Handy as “The First Successful Blues Published.” Its success not only comes from its publishing, but arguably its legacy as a standard as performed by various blues and jazz artists. For the sake of the length of this blog, I am going to include 5 performers who are icons for their place in jazz history: Bessie Smith, Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Dave Brubeck, and the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra.

In Bessie Smith’s version, she ignores the tango-like interlude and the beginning she enters with the melody and the 12-bar blues form, accompanied by an organ and none other than Louis Armstrong responding on trumpet to her lyrics [2]. Her version may not be authentic to Handy’s original composition, but she owns this version and it well represents the NOLA jazz sound:

Moving into the swing era, with the likes of big bands such as Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Cab Calloway, and, as I will present here, Glenn Miller. The Glenn Miller Orchestra was very well-known for its standards like “Pennsylvania 6-5000” and “In the Mood,” but when Glenn Miller was enlisted to serve in Europe during World War II, he made sure to keep his music going. Here is his version of St Louis Blues presented as a march:

From the Swing era, jazz musicians started to get a little more adventurous with exploring different textures in rhythm and harmony. Musicians like Charlie Parker, Max Roach, and Dizzy Gillespie were at the forefront of the bebop era by taking old standards such as St Louis Blues and creating bebop-ified version of their roots in Handy’s composition. Here is Dizzy Gillespie’s version, this time featuring the tango interlude that could likely be attributed to Dizzy’s fondness of Afro-Cuban music as he explored in “Manteca” or “A Night in Tunisia”:

On the other side of the same coin, West Coast cool jazz coexisted with bebop as a mainstay in jazz music in the ’50s and ’60s. Still using the St Louis Blues standard, Dave Brubeck also uses that tango beginning, but goes into the form with a lighter feel in comparison to Dizzy Gillespie, which is apparent in Paul Desmond’s improv solo, which couldn’t possibly be lighter or more laidback:

To close the blog post, I leave you with Bob Brookmeyer’s arrangement of St Louis Blues as performed by the Thad Jones/Mel Louis Orchestra. While it may not necessarily be faithful to Handy’s original idea for St. Louis Blues, it represents a culmination of St Louis Blues’ place in jazz history:

Sources:

[1] Hagstrom-Miller, Karl. “How Blues Became Folk Music” in Segregating Sound (North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2010). 241-274.

[2] Smith, Bessie. “St. Louis Blues” on Nobody’s Blues But Mine. Future Noise Ltd., 2008, Streaming Audio. https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Crecorded_track%7C1018361.

[1]

[1]

[2]

[2] [2]

[2] [3]

[3]