Screen Shot from March of Time “Night Club Boom”

Screen Shot from March of Time “Night Club Boom”

March of Time, in 1946, did a feature on the boom in night clubs in the United States. For relevant numbers, March of Time cites that there were 70,000 nightspots in the U.S. is 1946. In the central hub of night clubs in the 40’s, New York was home to several thousand of that number.

Clearly nightclubs were prevalent in society, so the roles that employees took in such spaces may reasonably reflect the standard across the U.S. at that time. It is incredibly striking how much March of Time emphasizes the various important role’s that females play in nightclubs. However, is is equally disappointing to see the women constantly referred to as objects for monetary gain.

The documentary starts by describing the various jobs at a nightclub. Once the narration moves past the roll of the door-man, they come to the job of the coatroom or “checkroom girls.” The narration describes that

In most clubs, the checkroom girls are hired at a fixed salary by an outside concessionaire. He picks them for the kind of personality that will attract tips and everything they collect goes into their employer’s box, which is securely locked.

The rhetoric implies a distrust to these girls, and emphasizes that their social interactions are strictly for monetary gain. Certainly, it would not have hindered the narration to indicate the useful service that these women provided for the nightclub.

In contrast to these women, the head waiter does not need to put his money in a lockbox to give to the employer. Rather, the head waiter is seen dealing with thrifty costumers by putting them at poor tables until they tip him generously. On screen, the costumer is seen giving the head waiter a $5 bill to change seats. This was drawn in direct opposition to the checkroom girls who received a half-dollar and needed to put it in a check box immediately.

This March of Time documentary short was meant as an education tool for those who did not go to nightclubs to understand their “social order.” The depictions in this documentary continue to label the women in the nightclub business as objects to be examined and payed according to their visual aesthetic while labeling the men in the nightclub business as individuals who grant a service. This, of course, reflects the social attitudes of mid 20th century America. Nevertheless, it is valuable to examine and take note of such subjugating examples because patriarchal attitudes certainly have not died out by the year 2017.

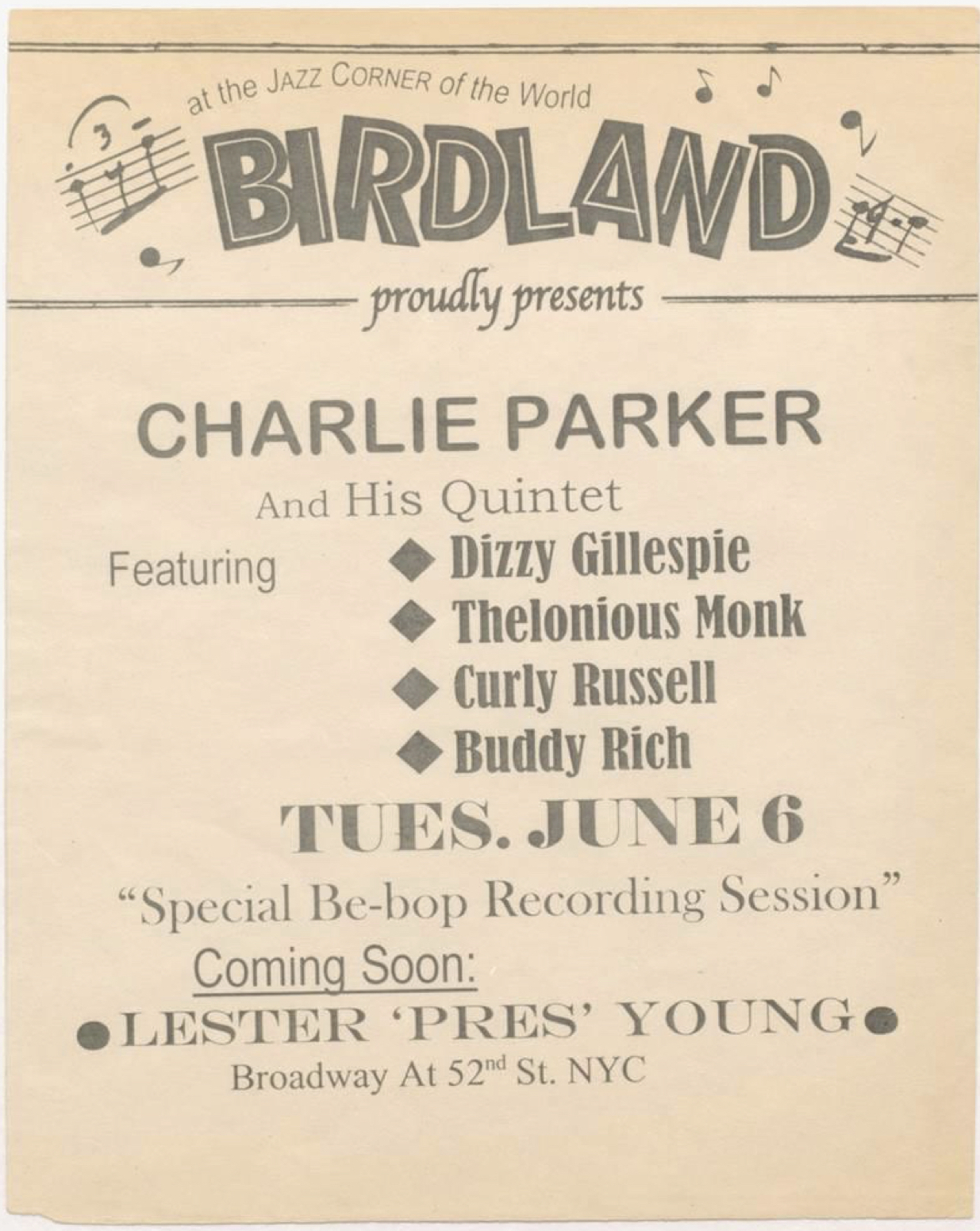

The value of this documentary short, specifically for american music, is its emphasis on nightclub culture. In the postwar era, genres such as bebop was born in late night club sessions (after the patrons would leave), but most of the music being played was dance music. The music itself is mentioned a number of times as an important key to success for any nightclub, but the individual musicians are never mentioned. This attitude toward musicians views them as providing a function service (much as how the checkroom girls are presented). These social situations are what provided the motivation for beboppers to focus their music on their own personalities.

One of the most prevalent clubs in Harlem was the Cotton Club, where Duke Ellington played frequently. Although Duke was not mentioned in the video, his music was played throughout. Therefore, I have left a song here for you to enjoy.

Works Cited