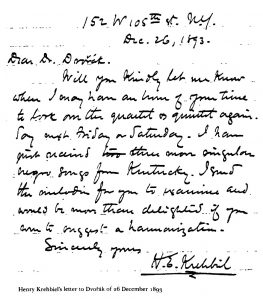

On December 26, 1893, the music critic and musicologist Henry Krehbiel corresponded with the famed Czech composer Antonin Dvorak (1841-1904). Two weeks prior, he’d conducted “a lengthy interview with the composer” for a New York Tribune article on Dvorak’s “Symphony No. 9 in E minor, ‘From the New World,’ Op. 95, B. 178,” before its premiere.[1] Krehbiel wished to speak to Dvorak on behalf of several Black “folk songs from Kentucky” he was analyzing and was requesting Dvorak help “suggest a harmonization” of the melodies.[2] Krehbiel—having lauded Dvorak’s music and sought his guidance on folk song collection—points to their mutual willingness to embrace African American’s contributions to folk music and develop an American school of classical music. Yet, while the cosmopolitan Dvorak straddled the line between universalism and individualism in his composition, Krehbiel’s romanticized view of slavery informing his approach to African American folk music reveals how problematic musical context can become overlooked in popular works.

Returning to the above-mentioned correspondence, it’s notable that on December 12, 1893, with four days to the “New World Symphony’s” premiere, Krehbiel had solicited Dvorak for a separate request. As Krehbiel was going to lecture on “Folk-Song in America” at a reception, he wanted Dvorak to “attend and hear the songs which I have for illustration.”[3] The reality that both men saw America’s musical “future…founded upon…negro melodies” positions them opposite universalist stalwarts in the debate of “What is American Music?”.[4] However, it also situates Dvorak adjacent to Krehbiel, who romanticized the notion of slave labor and experience as “inviting celebration in song—grave and gay.”[5] Krehbiel brutishly brushed over the idea of African American’s epigenetic trauma through stating, “sometimes the faculty [cultural ingenuousness] is galvanized into life by vast calamities or crises of social and national existence; and then we see its fruits in the compositions of popular musicians.”[6] Dvorak’s association with Krehbiel’s problematized musicological methods calls into question a key controversy surrounding American music—when traditional African American melodies injected deeply into our cultural consciousness are predicated in racist assumptions, should they still be performed? Without due consideration of the cultural context in which pieces are created or popularized, canonical works like Dvorak’s “Symphony No. 9” may remain mired in the overwhelmingly murky history of American Music.

[1] ed. Michael Beckerman, “Letters from Dvořák’s American Period: A Selection of Unpublished Correspondence Received by Dvořák in the United States.” In Dvorak and His World, 192–210. Princeton University Press, 1993. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7s5r0.11.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Douglas W. Shadle, Orchestrating the Nation: The Nineteenth-Century American Symphonic Enterprise, New York: Oxford University Press, 2016, 246.

[5] Henry Edward Krehbiel. Afro-American Folksongs: A Study in Racial and National Music, 4th edition, New York: G. Schirmer, 1914, 23.

[6] Ibid, 22-23.

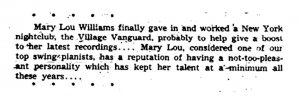

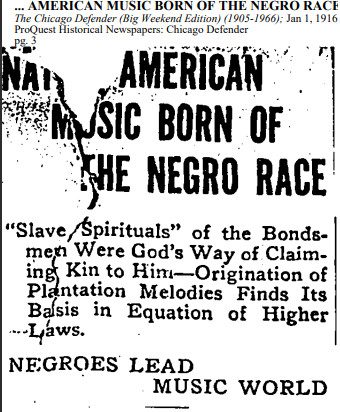

this question for an entire semester. According to The Chicago Defender, it is the song of the enslaved people that truly inspired (or birthed, in their own words) American music. The beginning of this article describes the argument that white people are the source of American music rather than that of bipoc and enslaved people. The Chicago Defender wastes no time in correcting this absurd sentiment. The author goes on to write about bipoc composers, writers and musicians. The author similarly takes a world view that all races are musical, and the truth of their being is expressed through their music. This I agree with, music expresses more than any other medium does. This expression, according to the author is one of divinity, and is an extension of God’s Way. While I don’t consider myself religious (a source of implicit bias I have) the sentiment of the author makes sense.

this question for an entire semester. According to The Chicago Defender, it is the song of the enslaved people that truly inspired (or birthed, in their own words) American music. The beginning of this article describes the argument that white people are the source of American music rather than that of bipoc and enslaved people. The Chicago Defender wastes no time in correcting this absurd sentiment. The author goes on to write about bipoc composers, writers and musicians. The author similarly takes a world view that all races are musical, and the truth of their being is expressed through their music. This I agree with, music expresses more than any other medium does. This expression, according to the author is one of divinity, and is an extension of God’s Way. While I don’t consider myself religious (a source of implicit bias I have) the sentiment of the author makes sense.