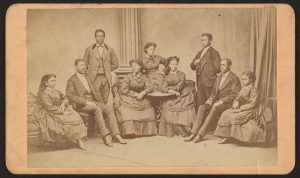

In 1870, Fisk University was going through some big changes. They were growing at such a rate they had to make plans to move locations(admittedly, a good problem to have). However, Fisk didn’t have the money for this ambitious plan. So, Professor and Treasurer George L. White came up with a gamble. Fisk would start a choir that would tour and raise funds for the school. White hadn’t been a singer himself, but had directed choirs in the past, and had already gathered $400 with a choir at Fisk for the benefit of their education. So, the Jubilee singers began, with a young Ella Sheppard serving as accompanist and director.

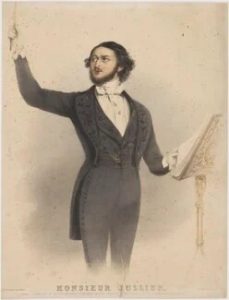

After their profound success in their famous 1871 tour, they set off again in the fall of 1872. They stopped by Steinway Hall in New York, the premier music hall in New York City at the time. This attracted much attention, and earned itself a review in “The Aldine, A Typographical Art Journal”. In its March edition, the author wrote in great detail of their experience hearing the Jubilee singers.

The 1871 Tour Fisk University Jubilee Singers From Left to Right: Minnie Tate, Greene Evans, Isaac Dickerson, Jennie Jackson, Maggie Porter, Ella Sheppard, Thomas Rutling, Benjamin Holmes, and Eliza Walker.

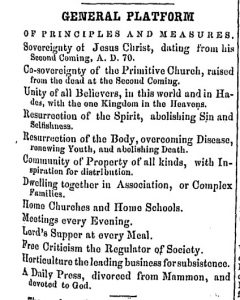

After giving a brief introduction to the Fisk Jubilee Singers, not unlike the one I’ve given you above, the critic started right into, to give them the benefit of the doubt, what surely they thought was a very earnest and not racist review of their performance. However, as I read through the publication, I was perplexed. The reviewer was giving the Jubilee singers these halfhearted, backhanded comments and compliments, saying things like “The personal history of these singers would be enough to make their concerts deeply interesting, even if their music was not very good. But, indeed, their music itself is admirable.” This is immediately followed by “They have, of course, no great cultivation”. There are various comments like this, a kind comment followed by a step back to recognize a flaw. This is, quite frankly, rude. Additionally, the critic refers to the singers as “impressionable minstrels”, their enthusiasm and expression as “grotesque, sometimes, but always genuine”, and the music itself as “clearly not the product of civilization” and lacking in “traces of the more scholarly music of the dominant race”.

The Fisk Jubilee singers redefined the spiritual for a wider audience, and used that audience to fund the education of hundreds of thousands of African Americans over the next 150+ years. The author of this article reflects how the Fisk jubilee singers were viewed by some at the time of their initial tours, not as artistic equals and scholars seeking to fund their program to further their educational endeavors, but as a lesser choir showing the songs of their people, trying to mimic the popular choral sound of the day. The review is by and for the people who were simply not ready for the Jubilee Singers.

Here is a 1909 Recording of the Fisk Jubilee Singers performing Swing Low Sweet Chariot.

Below is a 2020 recording of Fisk’s Jubilee Singers performing Walk Together, Children (Arr. Moses Hogan).

Black, James Wallace. Jubilee Singers, Fisk University, Nashville, Tenn. 1870-1880, Library of Congress, https://lccn.loc.gov/2010647805

“George Leonard White.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/singers-white/. Accessed 1 Oct. 2024.

“MUSIC.: THE JUBILEE SINGERS.” The Aldine, A Typographic Art Journal (1871-1873), vol. 6, no. 3, 03, 1873, pp. 67. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/magazines/music/docview/124830318/se-2.