Recording of “Venimos de Matamoros”:

https://latinoamerican2.abc-clio.com/Tools/DisplayVideo/2265362?view=content

Mexican influence is seen all over the United States both geographically and historically. This is especially so in the southeastern region as there were many native Mexicans in that area of the U.S. when that region of the country was annexed through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. Music plays a large and important aspect in Mexican influence on U.S. culture. The main focus of this post is this Primary Source recording done in 1939 by José Suarez1.

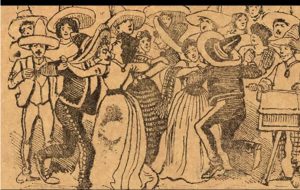

The song is called “Venimos de Matamoros” which translates to “We Come from Matamoros” – a town off of the Rio Grande. It falls into the category of Mexican folk songs called “corridos” which translates to “racing”, possibly in reference to the fact that these songs are usually more upbeat in tempo. In addition to its traditional tempo, this “corrido” also maintains traditional instrumentation of a single guitar as well as a solo repetitive melody line.

“Corrido’s” originated in 16th century Spain with traveling musicians or “trovadores” in a décima2 format consisting of ten lines3. In the Mexican tradition, “corridos” were added to by women in Mexico during the Mexican Revolution which took place from 1910-1917. The tradition was then carried into Texas in 1915 when it is believed the story of the song takes place. In a nearby town to “Matamoros” called “Brownsville” where Texas rangers killed the family(wife, son, and brother) of a man named Aniceto Pizaña. This event caused Pizaña to seek revenge and join the group of Mexican Americans against the White Americans taking land and causing conflict in Texas at the time. In comparison to the original 16th century “corridos”, the 19th century version served as a narrative to tell stories of heroism and strength as well as maintain a Mexican Identity in the midst of expansionism. In “corridos” regarding the United States and expansionism, the songs often tell stories of those who were killed(by usually white Americans) in honor of the sacrifice they made.

Much like other marginalized groups of America, Mexican Americans used music to find identity and peace in the forceful “othering” that was being cultivated at the time. The bigotry and discrimination that was faced became an aspect of Mexican American identity, separating this new identity from that of being “Mexican” and from being “American”. Both of these countries began through colonization, thus furthering the struggles portrayed in “corridos”. Today “corridos” are considered a subgenre of American folk songs, even though it went through many cultures and countries starting with Spain, going to Mexico, then to the independent Republic of Texas, and finally to the United States.

1 “Venimos De Matamoros’ [3:13].” The American Mosaic: The Latino American Experience audio. 2024. Accessed October 1, 2024. https://latinoamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/2265362.

2 Kanellos, Nicolás. “Décima.” In The American Mosaic: The Latino American Experience, ABC-CLIO, 2024. Accessed October 1, 2024. https://latinoamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/1448550.

3 Wood, Andrew G. “Borderlands Music.” In The American Mosaic: The Latino American Experience, ABC-CLIO, 2024. Accessed October 1, 2024. https://latinoamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/1367240.

This first photo is taken from a popular (in the 1800s) cartoon by Currier and Ives called Blacktown, a satire aimed at making fun of black people. Its one of the first images that results from the search of the word “banjo,” yet we know that banjo was a popular instrument in black communities. Its a useful source to pair with Southern and Gidden’s points, because it places the banjo in the black musical canon, yet it’s entirely controlled by the white people who made it.

This first photo is taken from a popular (in the 1800s) cartoon by Currier and Ives called Blacktown, a satire aimed at making fun of black people. Its one of the first images that results from the search of the word “banjo,” yet we know that banjo was a popular instrument in black communities. Its a useful source to pair with Southern and Gidden’s points, because it places the banjo in the black musical canon, yet it’s entirely controlled by the white people who made it. This picture, from 1901, is of a “picaninny” performing child, a popular vaudville act, in which children performed for white spectators, often for humor, under the hand of a white adult female. The children often travel with the troupe without their families. Again, the mandolin places the instrument into the black music narrative, but the picture is likely taken by a white person for other white people. I find this picture especially disturbing, as the child is nameless, naked, and smiling (is she happy?). She is viewed as an object for entertainment; property to the act. This is another example of white people in control: not only of the picture and narrative, but of the life of this child.

This picture, from 1901, is of a “picaninny” performing child, a popular vaudville act, in which children performed for white spectators, often for humor, under the hand of a white adult female. The children often travel with the troupe without their families. Again, the mandolin places the instrument into the black music narrative, but the picture is likely taken by a white person for other white people. I find this picture especially disturbing, as the child is nameless, naked, and smiling (is she happy?). She is viewed as an object for entertainment; property to the act. This is another example of white people in control: not only of the picture and narrative, but of the life of this child.