In the spring of 1917, America officially went to war. “The Great War”, “The War to End All Wars”, Americans at the time called it. For some, it brought back some not-so-happy memories from the American Civil War. Naturally, the Ziegfeld Follies decided to do a song about it.

“The Dixie Volunteers” is a song composed by Edgar Leslie and Harry Ruby for the Ziegfeld Follies, a theatrical production consisting of many musical and sketch acts, and a pioneer of the popular theater forms of the day. The Follies would often attract sought-after stars, notably, Bert Williams, as touring was not necessary due to the Follies being produced on Broadway. “The Dixie Volunteers” was sung by Eddie Cantor, the year of his debut on the Follies. He would stick around for another ten years, performing in blackface with Bert Williams and in other acts.

The song itself is an ode to the southern men who volunteered to go serve in the first World War. It begins like many standard war songs of the day, describing the men all lined up, marching, getting ready to set sail, and how badly they are going to beat the enemy. Upon the chorus, however, the song arrives at a point that is a common feature of many popular songs of the day, which is romanticizing the “old south”, before reconstruction. The lyrics tell us about how they’re coming from “the land of Old Black Joe”, a minstrel song about a dying slave, and about how they’ve gone from “peaceful sons” to “fighting men like Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee”.

This song reflects the common trend of the day of romanticizing the old south, a famous example of which is Louis Armstrong’s “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South”. This song could be offering an appeal to a broader audience as opposed to just the people in New York City who happen to see Broadway Shows. Apparently it worked, as according to Karen Cox, author of Dreaming of Dixie: How the South was created in American popular culture it became incredibly popular. The idea she suggests in her book of music and film and theatrics contributing to the romantic Southern image corresponds strongly with the common ideas of how the Southern image was formed.

League, The Broadway. “IBDB.Com.” IBDB, www.ibdb.com/broadway-cast-staff/eddie-cantor-5198. Accessed 22 Oct. 2024.

Leslie, Edgar. Composer. “Ziegfeld follies (1917) Dixie volunteers.” Digital Gallery. BGSU University Libraries, 23 May 2022, digitalgallery.bgsu.edu/items/show/33991. Accessed 22 Oct. 2024.

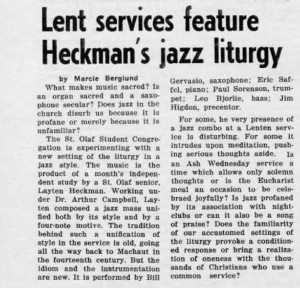

It seems St. Olaf has been hesitant to embrace Jazz as a sound musical genre, especially in regard to liturgical music. In this 1968 article of the Manitou Messenger, Ms. Berglund summarized a student jazz liturgy setting performed in chapel and asks questions that point to Jazz as a potentially profane and intrusive art form for worship. “Is jazz profaned by its association with night-clubs or can it also be a song of praise?”[1]

It seems St. Olaf has been hesitant to embrace Jazz as a sound musical genre, especially in regard to liturgical music. In this 1968 article of the Manitou Messenger, Ms. Berglund summarized a student jazz liturgy setting performed in chapel and asks questions that point to Jazz as a potentially profane and intrusive art form for worship. “Is jazz profaned by its association with night-clubs or can it also be a song of praise?”[1]