The first off-reservation boarding school in the U.S. for Indigenous students, Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was founded in 1879 by Henry Richard Pratt in Pennsylvania. The founding of the school was overseen by President Rutherford Hayes, under the Indian Civilization Act (ICA), that incentivized the so-called “civilized” education of Indigenous children. Carlisle’s strict, military-style modes of discipline and focus on vocational training that funneled students directly into underpaid manual and domestic labor jobs became a blueprint for several such boarding schools across the country.1

Since the recent archeological discoveries of mass graves at the former sites of these schools across the US and Canada, the legacy of these institutions designed to “kill the Indian, save the man,” in Pratt’s words, is being examined again with a mind towards restorative justice, acknowledging how these modes of “education” and assimilation were not just physically violent, but also mentally and spiritually violent.2

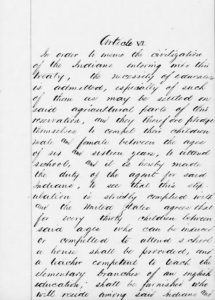

One would not necessarily expect music to play a central part in the violent assimilationist education of these boarding schools, but a 1915 book giving detailed instructions, down to how much time in the school day should be spent on a subject, for boarding school curriculum suggests otherwise. The book features a chapter outlining the music curriculum, which is extremely telling of the strict assimilationist thinking that was the guiding force for these boarding schools.

The first paragraph seems innocent enough, touting the broader educational benefits of music training, but it quickly takes a turn. The author(s) of this guide state that the first step in a proper musical education is “to permit the pupils to hear only good music.”3 What exactly they mean by “good,” is quickly outlined by a long list of operas such as Aida and William Tell, as well as works from the Western classical canon by composers such as Mozart and Haydn. They also add that “Patriotic songs, as ‘The Star Spangled Banner,’… should, of course, receive special attention.” 4

Following these narrow and purposefully Euro-centric repertoire guidelines, the author(s) go on to list aesthetic guidelines for the training of the pupils’ voices. The very first rule stated is “Always insist on a good, smooth, sweet, light, pure tone.”5 Soon after that, it’s also stressed that the pupils “Pronounce all words clearly, so that a listener can understand them.”6 These two guidelines emphasize the enforcement of Euro-centric standards for musical training, as well as complete assimilation to the English language and abandonment of Indigenous aesthetics and language.

With strict guidelines to teach and enforce the European classical canon as the musical ideal, Indigenous children, often as young as four years old, were completely cut off from not only their home and family, but also the musical culture they would have otherwise been surrounded by and raised in. The violence lies not only in hundreds of deaths of children that were torn from their homes, but the systematic way in which they had their culture and traditions torn from them, and the Indigenous music and languages that were lost in the process.

1 Ferris, Jeanne. 2021. “‘LET THOSE Children’s Names BE KNOWN’: THE PARADOX OF INDIAN BOARDING SCHOOLS.” News from Native California 35 (2): 26–32. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=154090702&site=ehost-live.

2 Ibid.

3 Bureau of Indian Affairs. 1915. Tentative course of study for United States Indian schools. Prepared under the direction of commissioner of Indian affairs. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, American Indian Histories and Cultures, http://www.aihc.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Details/Ayer_386_U5_1915 [Accessed October 26, 2023].