During the Depression, American concert life survived on patronage, but that was hardly enough to keep them afloat because potential audiences didn’t have the financials to attend live performances. Audiences turned to radios to listen to orchestras and the invention of sound film eliminated the need for silent film orchestras. The first half of the Depression left about 70% of all musicians unemployed, and the government was able to create the Federal Music Project to support these musicians. At its peak, the program employed 16,000 musicians and supported 28 symphony orchestras, creating more abundant access to music.

However, America’s post-Depression concert life thrived more than it had before. Thanks to the efforts of musicians during the Depression, concert halls were bringing in broader and larger audiences than ever before. The episode Upbeat in Music from Time Magazine’s The March of Time discusses America’s post-Depression concert life. One of the highlights of classical music’s growing audiences was the healthy state of 200 symphony orchestras (compared to the 28 government-backed orchestras of the Depression).

Perhaps the biggest accomplishment in concert music directly following the Depression years was the American Federation of Musicians’ efforts for royalties in 1943. Because the Depression put such an emphasis on radio broadcasts and recorded music, the AFM made a move to fully share the profits made from commercial use of recorded music. James Caesar Petrillo, AFM’s president, led these efforts; he demanded that royalties on classical recordings be paid to a union employment fund and forbade union musicians from performing for any recording company. Despite heavy public criticism, he was backed by 138,000 union members and they found success when all but the two largest recording companies of the time agreed to their terms. With the success of these efforts, the AFM used these funds for the advancement of live concert music.

Crawford, Richard. America’s Musical Life. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001.

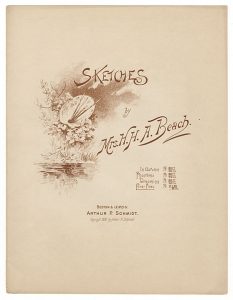

In September 2017, the New York Times honored Amy Beach’s 150th birthday with an article on her life and works. The biggest takeaway I found in this article was that her “Gaelic” Symphony shot her to compositional fame, but no orchestras have programmed hersymphony or any of her orchestral works for this season. While Beach experienced sexism at the height of her career, it is clear that sexism in classical music is still alive and well when none of our major orchestras will honor her works on this anniversary.

In September 2017, the New York Times honored Amy Beach’s 150th birthday with an article on her life and works. The biggest takeaway I found in this article was that her “Gaelic” Symphony shot her to compositional fame, but no orchestras have programmed hersymphony or any of her orchestral works for this season. While Beach experienced sexism at the height of her career, it is clear that sexism in classical music is still alive and well when none of our major orchestras will honor her works on this anniversary.