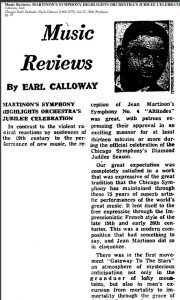

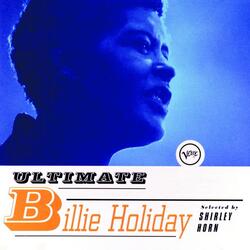

Music critics are a unique source as they show insight on how the audience perceived the performance at that point in history. Combined with general knowledge of the time period, they are incredibly useful to historians and musicologists. Earl Calloway wrote a multitude of music reviews for the “Chicago Daily Defender” beginning in 19631

. This specific review is on the Chicago Symphony’s performance of “Symphony No. 4 ‘Altitudes’”. This piece was composed in 1964 by French composer Jean Martinon.

This music review is especially revealing of the audience reaction because Calloway begins by comparing the audience’s positive reaction with the generally negative one in the previous century. This reaction was in reference to new music as opposed to orchestras playing beloved classics. Calloway moves on to Martinson’s piece and attributes each of the three movements to the title’s theme of nature as well as an aspect of God. It is unclear how religious the piece was supposed to be in regards to what Martinon wanted. The final movement is called “the crossing of the Gods” and there are references to nature and the world at large(words like “stars” and “garden”), so there is an assumption of a spirituality present that could be made. The blatant portrayal of religion towards a general audience is a cultural norm that is not as present in modern day performances.

At the end of his review, Calloway explains that the piece was inspired by themes and variations of Frederick Stock and that “Altitudes” was a memorial to him. This provides evidence that the audience of the time held a value of memorial and legacy and the artistic talents of composers.

This is a recording of the Jean Martinon’s “Symphony No. 4” . While it is not the Chicago Symphony, it gives an idea of some of the musical ideas Calloway was referencing in his review.

References:

1“Earl Calloway’s Biography.” The HistoryMakers, www.thehistorymakers.org/biography/earl-calloway-39. Accessed 21 Nov. 202

2 Calloway, Earl. “Music Reviews: MARTINON’S SYMPHONY HIGHLIGHTS ORCHESTRA’S JUBILEE CELEBRATION.” Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973), Jan 12, 1966, https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/music-reviews/docview/494213409/se-2. Accessed November 21, 2024.