In a democracy at war, the cultural values of a young and vigorous nation can and must be preserved.

The closing lines of Upbeat in Music echo the rising nationalist sentiment that permeated America in the 1940s. This film, originally premiered in 1943 catalogues the musical year. And if one quote can sum up America’s musical life in the middle of World War II, it is certainly the one listed above. Upbeat in Music is a short documentary put together by newsreel makers, the March of Time. This year, 1943, in particular is compelling. America was in the middle of World War II and the nation’s sole preoccupation was establishing a strong national identity. Music was not spared from this endeavor. In fact, music is perhaps one of the great definers on American musical identity. This short film while attempting to discuss only 1943 ended up encapsulating the spirit of American Music as a whole in a few key ways.

First, the entire film is preoccupied with the definition of “American” sound. To be fair, the film was made during a time of increasing nationalist fervor. World War II was in full swing and music was not be be exempt from the military industrial complex. In fact, the film points out throughout WWII the US Government printed in “hit kits” (books of five American songs and one song by an Allied Nation) that would be given to soldiers in the field. What got to go inside of the hit-kits was hotly contested. So much so that the government formed Music Committees of msuicians and impresarios like Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, and Paul Whiteman to determine which pieces of music were “American” enough to be included. At this crucial time in history, it became incredibly important that America establish a cohesive musical identity. And the most American way to establsih and American musical identity is certainly through the formation of a government committee.

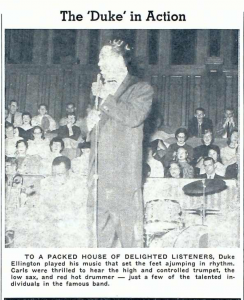

Even after the reel moves on from talking about World War 2, it continues to emphasize a true “American” sound. The reel describes the efforts of American composers to create Americna works, referring to the compositions of Duke Ellington, Virgil Thomson, and Aaron Copland. Later, the video goes on to describe the way the Jukebox is changing the music industry and discusses the way musicians are struggling to maintain credit for (and therefore profit from) their work. This struggle reflects a another aspect of American music as a whole: the duality of the musician both as an artist and businessperson. The film spends a great deal of time talking about Serge Koussevitsky and the BSO and acknowledging the Metropolitan Opera and several large symphony orchestras as both important business and important artistic forces.

The last section of the film focused heavily on popular music, pointing out that the American musical landscape is predominantly molded by the desires of a white, middle class market. This too is present throughout all of American music hisotry, the idea of capitalism and music coinciding. The presence of these sentiments from a documentary in the 1940s only proves that markets for music have been driving forces behind musical development in America long before the new millenium.

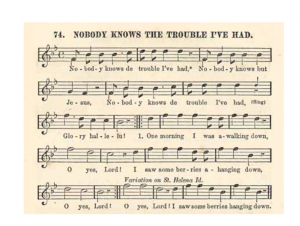

The film discusses the growing importance of jazz and recognizes the importance of Marion Anderson‘s recordings of spirituals as well, only briefly touching on the subject. While the film does discuss composers like Duke Ellington and performers like Anderson, it is also important to not the racist overtones that permeate the work. Nearly every person in the film is white, and when Ellington was brought up, through praised for his work in jazz, he was contrasted against “serious” composers like Copland and Thomson. Paul Whiteman was considered to be the standard bearer for jazz when it came to determining what should go into the “hit-kits” rather than someone like Duke Ellington who had a great deal of experience in the subject. In fact, no person of color was allowed on the “hit-kits” committee. As I said earlier, this film succeeds in painting a complete picture of American music history, and that history includes racism.

The film closes with the patriotic images of young soldiers giving recitals and the reminder that “In a democracy at war, the cultural values of a young and vigorous nation can and must be preserved”. For a nation at war, the preservation and definition of musical culture was of utmost importance. Upbeat in Music serves both as a time capsule and as an example of the major themes in American musical history. It is an invaluable insight into the ways music interacts with politics, culture, and economics as well as the way we talk about and research music.

Sources