Duke Ellington was one of the preeminent band leaders of the early 1900s. He was one of the key figures in the swing band industry and his band was among the longest enduring and more successful of the time. In addition to key musical contributions to the swing genre and Jazz at large, Ellington was a advocate for social justice and fought against discrimination and segregation1.

The swing band era in general was rife with discrimination as record companies had all the power and prioritized deals with white bands at the time. In addition, performance venues were highly segregated, giving priority to white led and white member bands2. Furthermore, the culture of the genre often led to band leaders being more in the spotlight, which combined with a set of racial stereotypes of the time often led to black led bands being more marginalized.

Ellington was also unique for his dedication to his musicians and because of his unique success as an arranger and seller of sheet music, he often relied on royalties to fund his band. His band had the longest running performance because as bands got more and more expensive to hold together, Ellington was willing to pay a premium price for his musicians and not even break even from concert sales. Although the long running prestige of the band boosted Ellington’s image, resulting in more sales of the sheet music.

In the 1940s, the Ellington band finally disbanded but Ellington’s impact on Jazz was still felt. He became a figure in the civil rights movement, embedding non-segregation clauses into contracts, composing works that drew interdisciplinary praise, and calling out appropriation.

Ellington’s impact these days is now seen as showcasing a unique and sophisticated development in Jazz music, highlighted by unique instrumentation, inventive arrangements, and strong stories.

1

Scott, Michelle R. “Duke Ellington’s Melodies Carried His Message of Social Justice – UMBC: University of Maryland, Baltimore County.” UMBC, UMBC Magazine, 19 May 2022, umbc.edu/stories/duke-ellingtons-message-of-social-justice/.

2

“Duke Ellington: ‘the Bandleader,’ Pt. 1.” NPR, NPR, 21 Nov. 2007, www.npr.org/2007/11/21/16321292/duke-ellington-the-bandleader-pt-1.

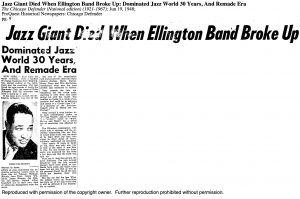

image

“Jazz Giant Died when Ellington Band Broke Up: Dominated Jazz World 30 Years, and Remade Era.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Jun 19, 1948. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/jazz-giant-died-when-ellington-band-broke-up/docview/492732663/se-2.