For this blog post, I decided to return back to and take a in-depth look at the American Indian Histories and Cultures archive. As we wrap up the semester and finalize our mapping projects, taking the time to locate more specific primary sources that relate to my group’s mapping project on Indigenous Song Collection and Repatriation is especially important.

The American Indian Histories and Cultures archive presents an array of resources that detail interactions between American Indians and Europeans from their earliest noted contact. The archives’ hope is to explore the consequences of European colonization on the political, social and cultural life of American Indians.

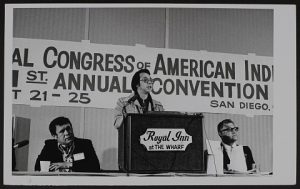

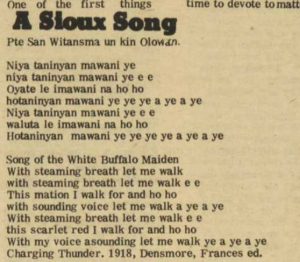

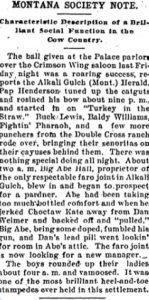

In a 1969 edition of The Indian, a song notated by Frances Densmore was published under the heading “A Sioux Song.” The newspaper was published by the American Indian Leadership Council in Rapid City. The Library of Congress associates the American Indian Leadership Council with the National Congress of American Indian:

“The National Congress of American Indian (NCAI) founded in 1944, is the oldest nation-wide American Indian advocacy organization of the United States… The Congress also aimed to educate the general public about Indians, preserve Indian cultural values, protect treaty rights with the United States and promote Indian welfare.”

Supposedly a product of an Indigenous right organization, The Indian randomly places Densmore’s transcribed lyrics of “A Sioux Song” within the paper. There is nothing that contextualizes the music beyond the fact that it is attributed to Charging Thunder and the Sioux people.

This article could be used as an interesting example of contrasting opinions on Frances Densmore’s song collecting work. On the one hand, “A Sioux Song” has been published within a larger collection of texts that speak to Indigenous rights and advocacy. Densmore’s song represents what the publishers saw as valuable information or knowledge that a reader could acquire should they wish to consider and evaluate Indigenous culture of South Dakota. On the other hand, this article also highlights some of the problems with Densmore’s work that we explore further in our mapping project (linked above). The lyrics that Densmore transcribed exist in a space without context and largely removed from their original meaning. It is surely a colonial idea to say that an audience is entitled to all of the information that the song contains, but considering the purpose of the newspaper and the legacy of Densmore’s song collecting work more broadly means that The Indian’s presentation of Densmore’s research might be a little too vague- not to mention that the column is titled “A Sioux Song.” Ultimately, the publication of Densmore’s “A Sioux Song” is an excellent example of some of the issues that my research group and I tried to parse out in our map and offers further examples of the value of considering context when studying music more generally.

Works Cited:

“National Congress of American Indians Records.” National Congress of American Indians records | National Museum of the American Indian. Accessed December 14, 2021. https://americanindian.si.edu/collections-search/archives/sova-nmai-ac-010?destination=edan_searchtab%2Farchives%3Fpage%3D1%26edan_q%3D%252A%253A%252A%26edan_fq%255B0%255D%3Dset_name%253A%2522National%2520Congress%2520of%2520American%2520Indians%2520records%2522%26edan_fq%255B1%255D%3Dset_name%253A%2522National%2520Congress%2520of%2520American%2520Indians%2520records%2520%2F%2520Series%25205%253A%2520Records%2520of%2520Indian%2520Interest%2520Organizations%2520%2F%25205.5%253A%2520Other%2520Indian%2520Organizations%2522.

Densmore, Frances. “A Sioux Song.” The Indian. December 1969, 9th edition. https://www.aihc.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/SearchDetails/Ayer_The_Indian_1969_12Dec_18#Snippits