While reading Eileen Southen’s passage about psalmody and hymnody practices in New England meetinghouses in the 1600s, I was interested to learn more about the separated and unseparated musical practices in the church based on skin color. Specifically, I was interested to learn more about when the separation of parish choir members shifted to include members of the black community — and why.

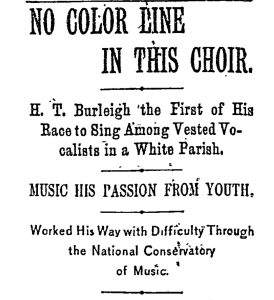

This curiosity led me to learn about H.T. Burleigh, dubbed “The First of His Race to Sing Among Vested Vocalists in a White Parish” by the New York Herald in 1894. The article highlights Burleighs trailblazing position as baritone soloist at St. George’s Church in New York City. The author, though unnamed, outlines Burleigh’s musical achievements, and throughout the article, praises all of the people that helped him along the way — people who are most likely white.

While I’m sure it is true that Burleigh received much help along the way, this help is what the article focuses on. In doing so, the author seemingly takes much of the focus away from Burleigh and instead focuses on the people who made his success possible for him. With the likelihood that the author of this article is also white, it is impossible to ignore how their own musical experiences and perspective influence the means in which Burleigh’s story is presented.

This writing and tone of this article is therefore like many others of its time when the subject is the accomplishments of African Americans and Black people in the United States in that it either highlights or focuses on the role that white people played in such accomplishments. The tone of these writings intend to take some or all of the credit for the success of Black people in America and instead contribute it to the resources and doings of white Americans.

A common theme in African-American and Black music-making, this portrayal of Burleigh’s success points to the overwhelming role that oppression played and has continued to play in American history. With this in mind, it is important to compare and contrast this primary source with other written histories in order to find the “truth”.

One way to do this is to read and learn about these histories in sources written by people with differing musical experiences, similarly to how we learned contrasting histories surrounding the origins and highlights of American bluegrass music. Though it is not a primary source, G. Yvonne Kendall’s recount of Burleigh’s career successes and highlights in The American Mosaic: The African American Experience paints a very different picture as to how Burleigh came to be the first Black chorister in a white parish, attributing it to his success at the Chicago World’s Fair.

This history considered, it is also hard for me to ignore the very title of this article, “No Color Line in this Choir”. The title attempts to diminish and ignore the role that race and ethnicity play in the lives and successes of African Americans and Black people. This title is nearly equivalent to the phrase “I don’t see color” and ignores the history and sacrifices that needed to be made in favor of continuing the oppression of African American and Black success.]

SOURCES:

Kendall, G. Yvonne. “Concert Music: 1861-1919.” The American Mosaic: The African

American Experience, ABC-CLIO, 2021,

africanamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/1591461. Accessed 28 Sept. 2021.

https://africanamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/1591461?terms=Burleigh&sTypeId=2

“No Color Line in This Choir.” New York Herald, 1894.

https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc

Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans : a History 2nd edition. New York: Norton, 1983.

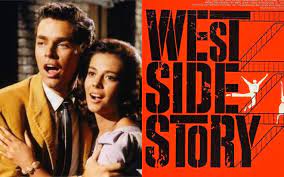

With the premiere of the 2021 film adaptation of West Side Story coming closer, I decided to look into the correspondence of Leonard Bernstein during the initial conversations with Arthur Laurents and others as they discussed the project. A well-loved and seemingly timeless production, West Side Story also puts the subjects of race and ethnicity on center stage, so to speak, and is well worth being discussed in context with the social issues at play during the time of its production.

With the premiere of the 2021 film adaptation of West Side Story coming closer, I decided to look into the correspondence of Leonard Bernstein during the initial conversations with Arthur Laurents and others as they discussed the project. A well-loved and seemingly timeless production, West Side Story also puts the subjects of race and ethnicity on center stage, so to speak, and is well worth being discussed in context with the social issues at play during the time of its production.