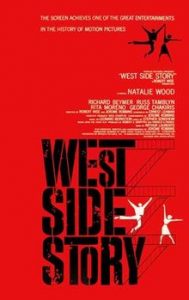

Above features the video “America” from West Side Story. Behind the distinctive Spanish rhythm and instrumentation Leonard Bernstein used, there are depictions of the Puerto Ricans’ experiences in their home country versus America. When the musical debuted on Broadway in 1957, it highlighted tensions between the Puerto Rican migrants and “whites” of New York. The song, “America” serves as a testament of an interpretation and stereotypes of the Latino migrant experience.

Migrants from Puerto Rico to New York exploded during the nineteenth century. In 1945, there were about 13,000 living in New York. That number reached a million by the 1960’s.1 One reason many migrated to New York was because they could make double the pay for the same work than what they were making in Puerto Rico, which was grappling with a depression.2 Meanwhile, New York Newspapers in the 1940’s and 50’s flashed daily headlines that emphasized the “whiteness” and good backgrounds of the victims, while painting the Hispanic assailants as unprovoked in their horrible actions. This tension between the Puerto Rican migrants that were seen as taking over the city and their conflict and strain with other minorities in the city became the perfect canvas for the musical.

The lyrics in “America” contrast between the Hispanic girls and guys (in the 1961 version and video above). The females are optimistic, hopeful in there lyrics “I’ll get a terrace apartment”, “Industry boom in America” and “free to be anything you choose.” On the male side, their response is less bright with responses like “Better get rid of your accent,” “12 in a room in America,” and “Free to wait tables and shine shoes.”3 The contrasting feelings about being in America represent disunity in their experience, just as the musical overall represents disunity and plots the Italians against the Puerto Ricans.

While the musical may be artificial in representing the Puerto Rican experience in New York in some ways, the violence between gangs and different ethic groups is accurate. In the musical, a fight ensues between the two gangs, mostly over pride that ends deadly for both sides. One New York Times article published in 1955 has a headline “Hoodlum, 17, seized as Slayer of Boy, 15.”4 As one can imagine, the article depicts the victim as “well mannered” and a “good student.” The “hoodlum” on the other hand, Frank Santana, shot him “seemingly unprovoked.” The gang violence in this article is similar to the musical, but the “culprit” does not get to just walk away and evade the police.

If Bernstein’s main goal was to create an authentic example of the Puerto Rican experience in “West Side Story,” there are certainly better ways it could have been achieved. He does however underline the optimism some migrants had for the new country and leaving their past behind. The reckless and problematic violence in the musical between gangs is also emulated, but is lacking in the targeted blaming migrants had to face that is evident in the plethora of articles published at the time. Overall, while West Side Story borders artificial is representing the Puerto Ricans, it is worth a watch and underlines issues faced by the Latino migrant.

1 “Immigration, Puerto Rican/Cuban” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/immigration/cuban3.html

2 Wells, Elizabeth A. West Side Story Cultural Perspectives on an American Musical. S.l.], 2010. http://portal.igpublish.com/iglibrary/search/ROWMANB0001881.html.

3 Sondheim, Stephen. © 1956, 1957 Amberson Holdings LLC and Stephen Sondheim. Copyright renewed. Leonard Bernstein Music Publishing Company LLC, Publisher. https://www.westsidestory.com/lyrics

4 Hoodlum, 17, seized as slayer of boy, 15: HOODLUM, 17, HELD IN SLAYING OF BOY. (1955, May 02). New York Times (1923-Current File) Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/113364015?accountid=351