We often focus importantly on the elements of minstrelsy which tie each troupe together; the costumes, dialect, racial humor, and urban audiences, however the Georgia Minstrels were breaking this tradition as early as 1876. Black people doing minstrelsy is complicated as though minstrelsy poked fun at Black people, the performing arts were one of a very limited number of spaces where Black people could occupy during the reconstruction era. 1 Although the idea of white people consuming Black performance art meant to dehumanize the performers is repulsive, the autonomy, creativity and talent of the Black performers involved should not be overlooked. The Georgia minstrels created for themselves a path to spaces where Black people could not occupy just over 10 years earlier. They were often asked to perform in vocal ensembles in churches and classical music performance venues, often part of a larger organized group’s performance.

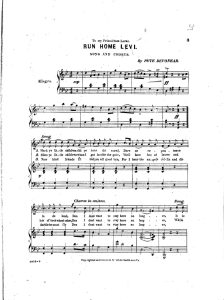

One such performance was on March 12 1876 at the Boston Theatre where the Georgia Minstrels were invited to perform at the Grand Sacred Jubilee Concert, featuring the Grand Jubilee singers and others presenting works by Haydn, Rossini and other classical composers as well as Negro spirituals. Here is one piece which is from Peter Devonear’s Plantation Songs (1878):

“Run Home Levi” from Peter Devonear’s Plantation Songs.3

Peter Devonear was a songwriter for the Georgia Minstrels who relied heavily on the conventional minstrel or “plantation” song rather than the spirituals. This piece is similar to many minstrel songs which invent new material for verses that rely on character creation, “Run home Levi, run home for de sun’s down.” The line, “Den I dont want to stay here no longer” then draws on plantation song sentiment. Eileen Southern writes of the intricacy behind an all-Black troupe performing songs rooted in slavery, “The Georgia Minstrels undertook to produce shows which were novel and distinctly ‘genuine,’ planation Black-American, and, at the same time enough in conformity with minstrel traditions to please their interracial audiences and keep them returning for more.” 2

One of the other groups on the program for the night were the Hyers Sisters, a group of three Black female performers who toured around the U.S. during the nineteenth century, impressing audiences with their musical talent. They, like the Jubilee Singers, performed repertoire in the Western music tradition yet are also an example of the opposition of Black performers to predefined role fulfillment. Jocelyn Buckner writes, “They pushed boundaries of acceptable and expected roles for black and female performers by developing works that moved beyond stereotypical caricatures of African American life.”4

Taking a look at Black performance groups during reconstruction has dramatically challenged my knowledge of racial power dynamics. In my opinion, criticizing minstrelsy for its racism alongside acknowledging the accomplishments of Black performers is one way in which students today can seek an antiracist, critical knowledge of American history. Of course this is just an opinion, and if you as the reader think I am misguided, I would love to hear what you have to say!