Throughout our long and complicated militaristic history, music has both shaped and reflected the public perception of the military. In my casual browsing of the Sheet Music Consortium, I began to notice patterns within the depictions of the military in both the art provided on the cover of the sheet music and the music itself, specifically with popular music written either pre or during World War I. As I dug deeper, I realized that I had seen these patterns before in the vast majority of post 9/11 country music.

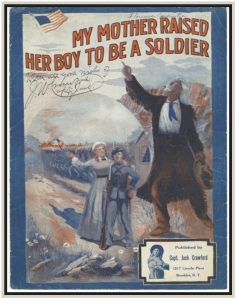

For the sake of conciseness, I’m going to focus on the lens through which these songs and their accompanying visuals portray the relationships between soldiers and the women in their lives. I found that many pre World War I songs depicted the soldiers’ relationships with their mothers as loving. These mothers are afraid to let their sons go to war, but nevertheless, proud and excited.

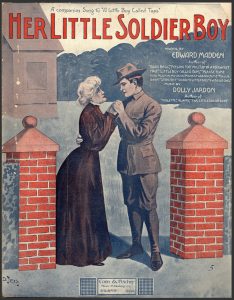

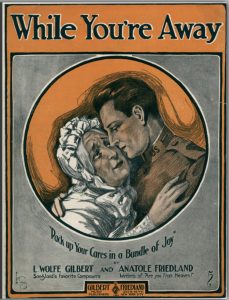

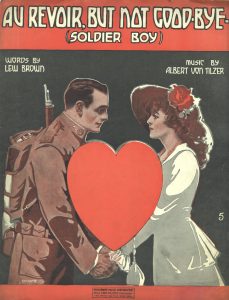

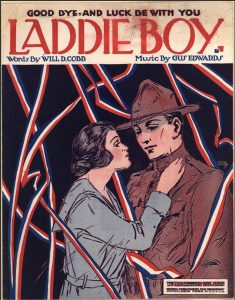

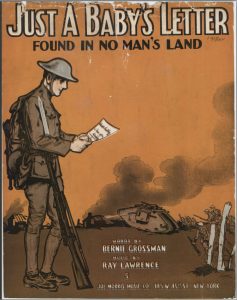

These songs also depict the soldi ers as sensitive romantic partners. Their small, waifish partners are left behind in their sadness and only have letters to sustain their love, and the sensitive soldier leaves with a heavy heart to do what he must to protect his love.

ers as sensitive romantic partners. Their small, waifish partners are left behind in their sadness and only have letters to sustain their love, and the sensitive soldier leaves with a heavy heart to do what he must to protect his love.

John Michael Montgomery song, released in 2004, “Letters from Home,” depicts a man in the army, and receives letters from both his mother and his wife.

Toby Keith, the country star who is the most egregious offender of post-9/11 pro-war propaganda, released “An American Soldier,” with an accompanying music video that depicts wives and mothers at home, desperately clutching letters and pictures of their strong soldiers.

The American military system has long relied on music to shape the public perception of itself. These examples from the post 9/11 era feel even more egregious to me, perhaps because we’re feeling the effects of these pieces of media more concretely and distinctly. However, the main difference between these pieces of propaganda is the efficacy with which the United States military funds these projects. Any movie that so much as mentions the United States military must be cleared by the Pentagon. Any positive depiction of any branch of the United States military is funded by the institution itself and therefore, a piece of propaganda.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Crawford, Jack. My mother raised her boy to be a soldier. Brooklyn, NY: Capt. Jack Crawford. 1915. http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/inharmony/detail.do?action=detail&fullItemID=/lilly/devincent/LL-SDV-261025

Edwards, Gus. Good Bye and Luck be with You Laddie boy. New York City, NY: Gus Edwards Music House. 1917. https://repository.duke.edu/dc/hasm/n0595

Gilbert, L. Wolfe. While You’re Away. New York City, NY: Gilbert & Friedland. 1918. https://dl.mospace.umsystem.edu//umkc/islandora/object/umkc:23894#page/1/mode/2up

Jardon, Dolly. Her little soldier boy. New York, NY: Conn & Fischer. 1906.

Keith, Toby. “American Soldier.” YouTube video. 4:29. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DWrMeBR8W-c

Lawrence, Ray. Just a Baby’s Letter Found in No Man’s Land. New York City, NY: Joe Morris Music Co., 1918. https://dl.mospace.umsystem.edu//umkc/islandora/object/umkc:22618#page/1/mode/2up

Michael Montgomery, John. “Letters from Home.” YouTube video. 4:29. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FIG9C3n-SPc.

Von Tilzer, Albert. Au Revoir, But Not Good-Bye, Soldier Boy. New York City, NY: Broadway Music Corp. 1917. https://collections.carli.illinois.edu/digital/collection/uic_smusic/id/5940