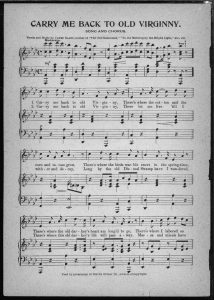

In our readings and listenings on minstrelsy, we have come across the minstrel song, “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny,” a sentimental tune seeming to long for simpler slave life back in the South. In an address to the State Legislature of Missouri, Dr. Joseph McDowell mentions this song as “the song of the old African,” arguing that it holds such a special place in the hearts and minds of former slaves because “no negro over left her soil but carried in his bosom a desire to return, and a vivid recollection of her hospitality and kindess”.1 The lyrics, pictured below, begin “Carry me back to old Virginny, There’s where the cotton and the corn and tatoes grow…. There’s where the old darkey’s heart am long’d to go.”

“Carry Me Back to Old Virginny” notated music, composed by James Bland. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas. 200000735/

“Carry Me Back to Old Virginny” notated music, composed by James Bland. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas. 200000735/

Written in 1878, the song was a “longtime staple” of minstrel shows2, a renowned favorite, bearing what we would deem now to be controversial lyrics. It was performed by many minstrel troupes, notably by the Georgia Minstrels, the “first successful all-black minstrel company,” of which the composer of this song was a prolific member.3 Furthermore, in 1940, the song was adopted by the state of Virginia as the official state song, and remained as such until 1997 when it was withdrawn due to complaints that the lyrics were racist, and was instead made the state song emeritus (an honorary state song).4

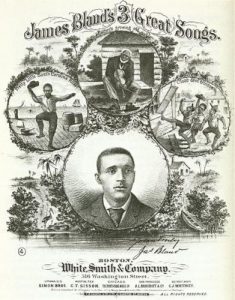

James Bland’s 3 Great Songs

http://www.blackpast.org/files/ blackpast_images/James_A__Bland __public_domain_.jpg

The element of this that I find most intriguing and complex is that the song was written by a black man, James Bland, to be performed in blackface minstrelsy. As we discussed in class, white people performing in blackface is an inappropriate and, quite frankly, a disgusting practice, but the morals get a bit trickier when it comes to black people performing in blackface. Bland used minstrel shows to his professional and financial benefit, using the stage as a platform to broadcast his musical compositions.5 In light of this, should we reconsider his song, “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny”? Is this a racist song? Or could it be a satire, “illustrating Southern white slaveholders’ longing for the past when they were masters and African Americans were under their subjugation”?6 Either way, is it wrong to discount a song that was a prominent feature of a man’s career that likely would not have come to fruition if it wasn’t for the popularity of minstrel shows, for better or for worse, blurring the color line and giving blacks the opportunity to participate in American popular culture?