The Monterey International Pop Festival in June of 1967 stands as a revolutionary musical event in which new and diverse performers captivated audiences and defined a new genre. The festival is notorious, even today, for providing an escape from the tumultuous socio-political climate and spreading messages of peace and togetherness. If we truly want to study these historical events with integrity, though, it is essential to challenge the notion that Monterey Pop transcended race in the way people say it did.

Monterey International Pop Festival, 1967

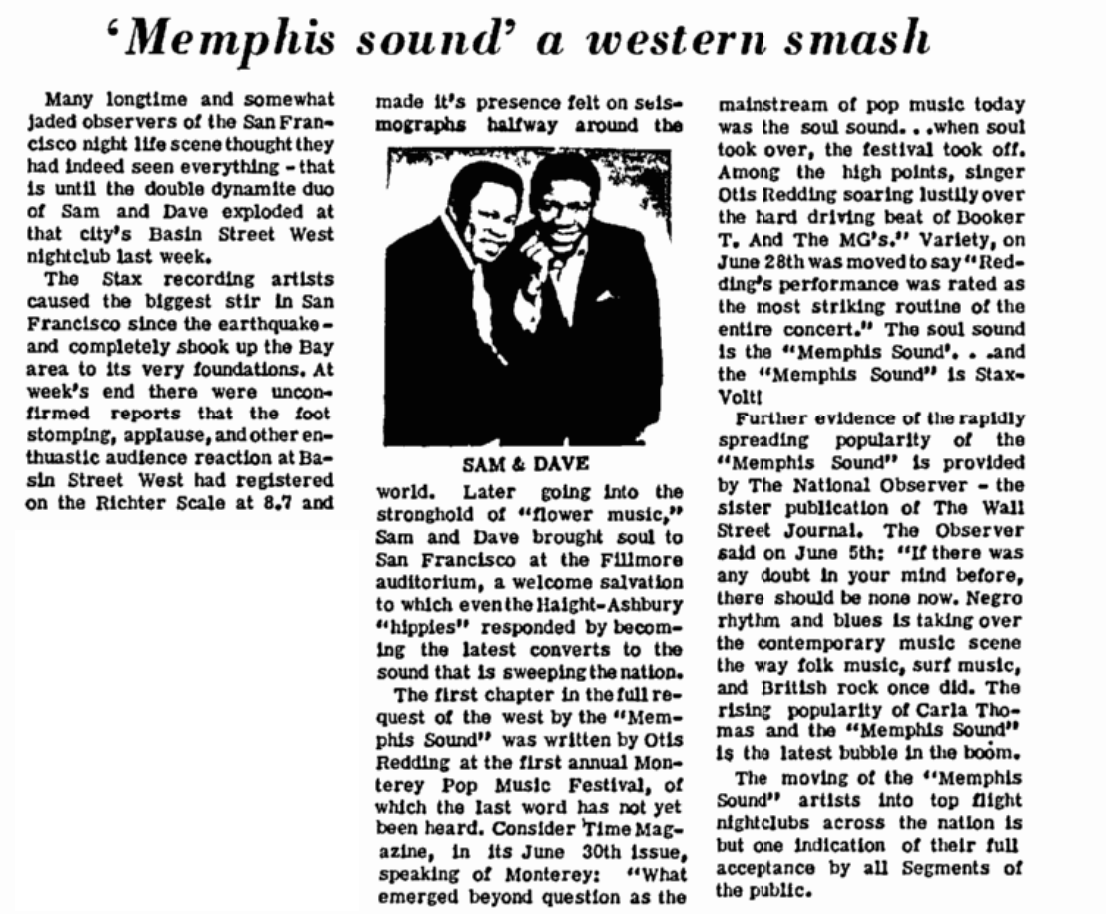

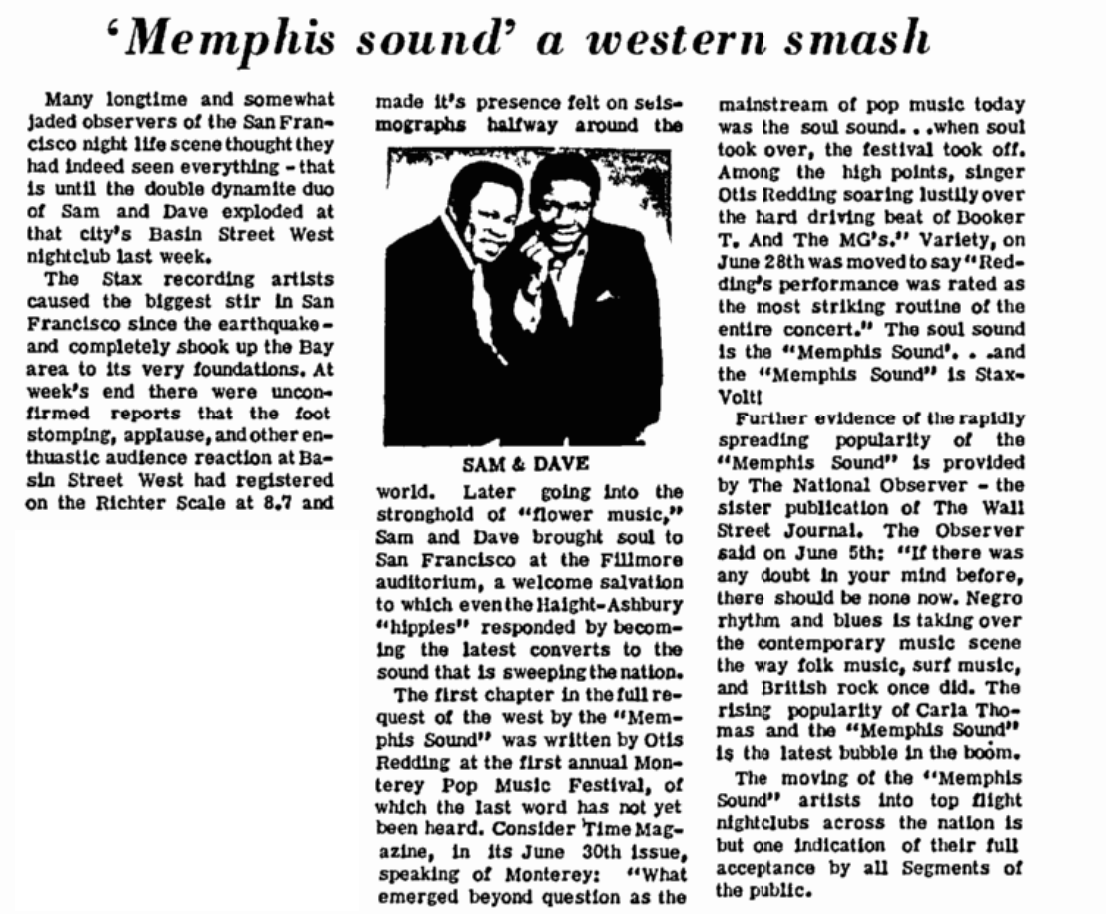

One way to analyze this idea is through an in-depth look at Otis Redding and his groundbreaking performance at the festival. An African American soul and blues singer from Georgia, Redding was relatively unknown at the time of his performance. For this reason, the universal praise from mostly-white audiences appears to be a win for African American culture – a true transcendence of race through music. On some level, this might be true; it’s likely that audiences genuinely enjoyed Redding’s performance, and Redding seemed to be all in on the hippie culture. What often gets swept under the rug, though, is that this reflects a larger phenomenon of neglecting to appreciate the rich and complex cultural history from which Redding and his soulful music emerged. A newspaper article written in August of 1967 subtly hints at this idea.

“Memphis Sound, a Western Smash” from Milwaukee Star, 1967

The article from the Milwaukee Star describes the early beginnings of Memphis soul/blues music in the San Francisco “hippie” culture. The author(s) attribute this to the popularity of Otis Redding’s performance at Monterey. Much like other literature on the festival, there is no explicit mention of race or how it was diminished. However, a close reading of the article, in my opinion, highlights an overall lack of appreciation for the black folk origins of Redding’s music. Furthermore, the author(s) speak with an optimism that suggests these black origins will now be recognized and understood by hippies in the West. Though soul and blues music definitely gained a larger audience because of Redding’s performance, I would be hesitant to say that this appreciation came to fruition in a complete and integral way.

Two present-day articles about the festival highlight this lack of understanding. First, one account from Consequence of Sound addresses Redding’s surprising catapult to fame, placing special emphasis on the peaceful nature of the festival that allowed hippie audiences to appreciate a performer like Redding. Yet, the article neglects to mention race, further negating Redding’s complete story and the history from which he emerged. More explicitly, one retrospective article from Billboard features written testimonies from who were at the festival 50 years ago. One account, talking about Redding’s performance, writes: “This whole audience of white, middle-class kids started screaming and acting like they were black. ‘Lord have mercy! Right on brotha!’ It was a little bit racist.” It’s likely that those white kids at the festival thought they were spreading love and acceptance, but this nevertheless demonstrates the racial colorblindness and privilege associated with the festival. The fact that this is one of few sources that mentions race highlights the erasure that did, and still does, occur. The festival was groundbreaking and peaceful, and did many wonderful things for Redding and music like his. Regardless, it’s important to acknowledge this lack of complete understanding, and work towards a more thorough appreciation of the origins of black soul music.

Sources:

Author Unknown. “‘Memphis Sound:’” A Western Smash.’” Milwaukee Star, August 12, 1967. Accessed April 4, 2018 from the African American Historical Newspaper Collection. SQN: 12CCE7DB1A225690.

Flynn, John, Randall Colburn, and Tyler Clark. “How Janis Joplin and Otis Redding Conquered Monterey Pop Festival.” Consequence of Sound. June 18, 2017. Accessed April 04, 2018. https://consequenceofsound.net/2017/06/how-janis-joplin-and-otis-redding-conquered-monterey-pop-festival/

Tannenbaum, Rob. “The Oral History of Monterey Pop, Where Jimi Torched His Ax & Janis Became a Star: Art Garfunkel, Steve Miller, Lou Adler & More.” Billboard. May 26, 2017. Accessed April 16, 2018. https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/magazine-feature/7809491/monterey-pop-oral-history-jimi-hendrix-janis-joplin.

Mavis Staples is an American Gospel and soul singer who rose to fame by being a part of her family’s band, the Staples Singers. She is also quite the civil rights activist, she even had the opportunity to sing for Martin Luther King Jr. Mavis began singing with her family at age 10 all the way throughout her education. In the Chicago Daily Defender, Staples is regarded as “another voice that ranks with Aretha’s.” 1

Mavis Staples is an American Gospel and soul singer who rose to fame by being a part of her family’s band, the Staples Singers. She is also quite the civil rights activist, she even had the opportunity to sing for Martin Luther King Jr. Mavis began singing with her family at age 10 all the way throughout her education. In the Chicago Daily Defender, Staples is regarded as “another voice that ranks with Aretha’s.” 1