I grew up on a farm. I have a recognizable Minnesota accent. I only call it “duck duck grey duck.”

These are not things I would have described as distinctive about myself as I was growing up. This is because I was surrounded by it. I felt no need to assert it as part of my identity – everyone around me also possessed these factors of identity. However, when I came to St. Olaf, a school where I am often surrounded by students from Oregon, New Jersey, Texas, and even other countries, my friends and peers informed me just how identifying these things about me are. I went to a place where I was no longer surrounded by people from my same background, and people pointed out things about me that made me distinctive to them. That made me all the more aware of my identity.

Similarly, in post-WWI America, Copland found himself studying in a new place entirely surrounded by something different: Paris. He grew up in New York at the turn of the century, the son of Russian immigrants, and he was thoroughly surrounded by the American soundscape. When he arrived in Paris, excited and determined to learn and make a living, he began working with Nadia Boulanger, respected and revered composer at the time.

Unlike Virgil Thomson, who pursued American music sound after being rejected from the Parisian music scene (saying it would be better to try and cultivate American sound than try to even break into the European scene), Copland turned to the American sound at the strong encouragement of his teacher, Nadia Boulanger.

One of the other students working in this class, Brandon Cash, also posted on this topic in 2015. Cash successfully outlines the strong relationship between Boulanger and Copland, especially highlighting the doors she opened for him in meeting other composers.

Compositionally, too, Boulanger’s abstract approach to jazz, which removed it from its cultural context and saw it as a purely compositional force, carried on into Copland’s work.

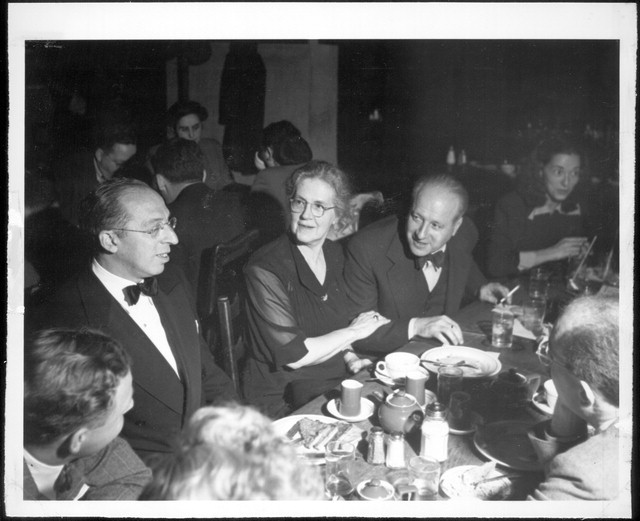

Source: Library of Congress

However, it is important to understand her importance in Copland’s development not as a middle woman between him and Stravinsky, for example, but as a valuable contributor in her own right. She encouraged him to define his American sound – otherwise he would crash and burn. Her blunt, heavily honest advice drove him to really define what he was trying to achieve in creating “American” music. Most importantly, she helped him realize that he had a unique identity in being American and having American sound, so he needed to focus and cultivate that. Like me, he didn’t realize he had certain distinctive aspects of his identity until he was in an entirely different place and someone else told him.

It is ironic that the vessel through which he found his American sound is in a Western European country. However, this is not surprising, given that the outside view of American music can give valuable insight just as the view from within. Boulanger did, indeed, encourage him to listen to other composers’ works, and after he heard Milhaud, Stravinsky, Ravel, and Debussy dabble in Jazz, he incorporated it into several of his works. These include Rondino, Symphony for Organ and Orchestra, Music for the Theater, Dance Symphony, and Piano Concerto.

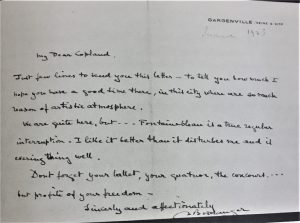

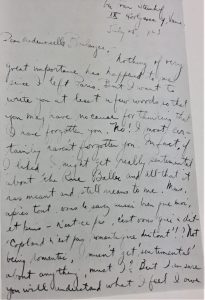

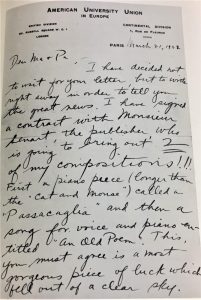

Below, these letters show Copland’s excitement at being in Paris and finding success and his correspondence with Nadia Boulanger.

Letter from Copland to his parents detailing his excitement at selling his first two compositions in Paris

Carole Jean Harris, “The French connection: The neoclassical influence of Stravinsky, through Boulanger, on the music of Copland, Talma and Piston.” State University of New York at Buffalo, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2002.

Annegret Fauser, “Aaron Copland, Nadia Boulanger, and the Making of an “American” Composer.” The Musical Quarterly, Volume 89, Issue 4, 1 December 2006, Pages 524–554.